Miriam Berchuk is on a diet.

She doesn’t call it a diet; instead, the Calgary anesthesiologist calls her way of eating a “food lifestyle.” Berchuk avoids breads, pastas and almost all fruits, and she’s lost 25 pounds in 19 months eating this way, often using recipes from a website called

Diet Doctor.

Her diet-cum-lifestyle, known as low-carb, high-fat (LCHF) eating, is one of the most talked-about trends in weight loss right now. One of the reasons why it’s easy to reframe as a “lifestyle” is that, in a lot of ways, it’s the opposite of what we’ve always thought of as “dieting” to lose weight.

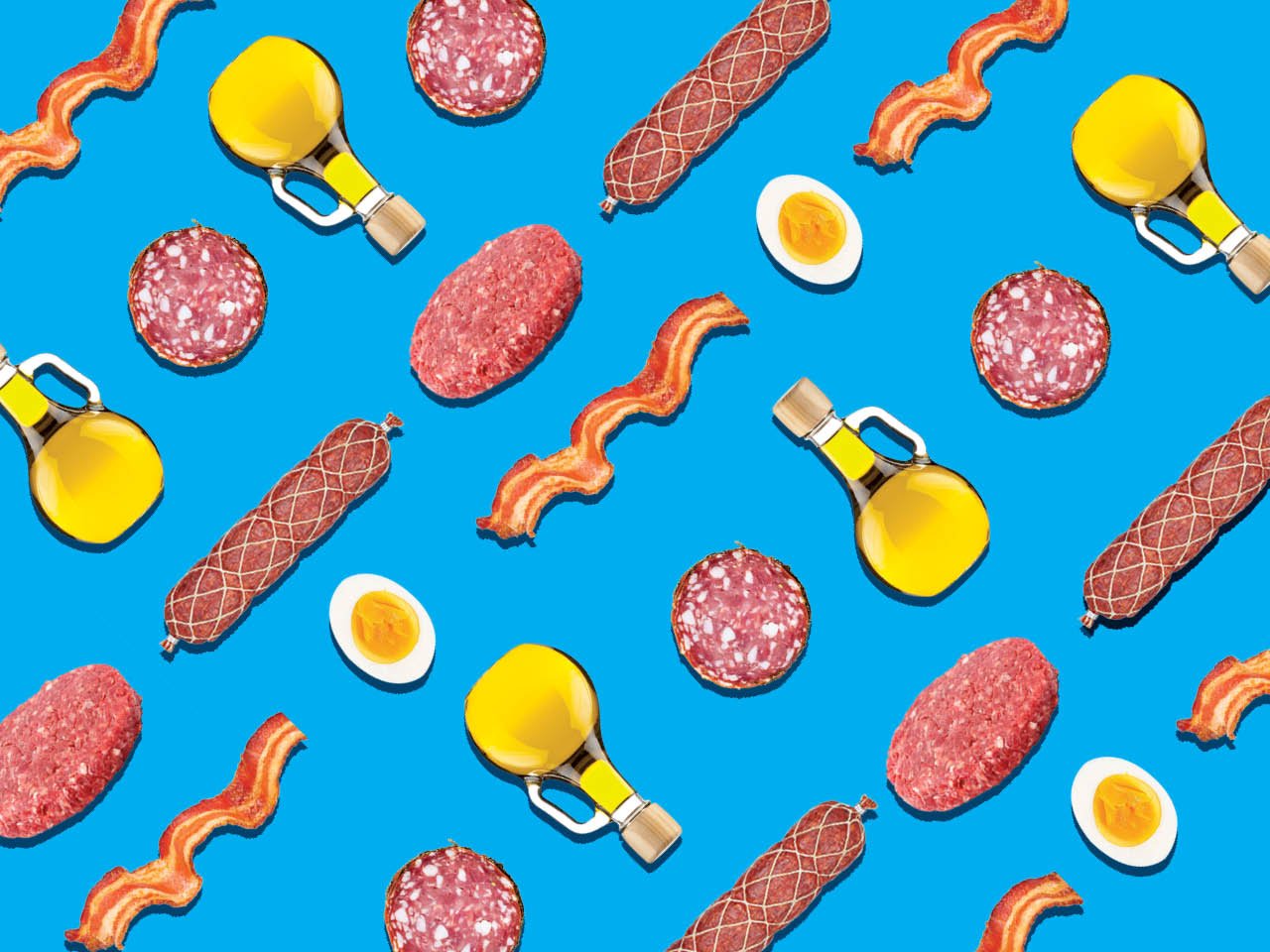

Here’s a taste of what Berchuk might eat in a day: To start, she skips breakfast. She’ll drink a coffee sometime in the morning, with a squirt of heavy cream. Lunch might be gourmet pepperoni sticks from a Canmore meat shop, with some cheese and veggies. A typical dinner might include an appetizer of cured meat, a salad with avocado and pomegranate seeds and a crustless quiche made with sweet potatoes and heaps upon heaps of Gruyère and havarti cheeses. She doesn’t count calories.

Lindy West on how to be a vibrant, happy fat woman

Lindy West on how to be a vibrant, happy fat womanBerchuk believes that our widespread fear of fat over the past half-century, enshrined in national

food guidelines and hawked by sellers of every processed food imaginable (low-fat bacon, fat-free cookies), is adding to our waistlines and causing an epidemic of diabetes. Her theory? When we eat more natural and whole-sourced fats, we feel more satiated and stop turning to empty filler foods that offer zilch in nutrients.

“When you give people permission to eat fat as part of a low-carb diet, they feel satisfied,” says Berchuk. “They enjoy what they’re eating and feel like they can do this forever.”

Berchuk is part of a group of Canadian physicians who have adopted, and become advocates for, a lower-carb, higher-fat, whole-food style of diet, believing this way of eating could help reduce our country’s obesity crisis.

The group got its legs in 2016 when four female doctors — none of whom are specialists in obesity medicine or nutrition — launched a closed Facebook group dedicated to this style of eating. They had all used an LCHF approach to managing

weight and metabolic issues but found little support among their colleagues. The foursome first connected while talking about their weight loss on a site for physician mothers, then moved to a place of their own — they had plenty to say and not everyone was interested in talking about a low-carb diet.

Nearly two years later, membership to their closed Facebook group has grown to more than 3,000 female doctors — a stat that suggests one in every 12 female physicians in Canada is a member. They trade recipes, share weight-loss success stories, discuss studies on LCHF eating (one extreme of which is known as the ketogenic diet) and vent about the ubiquity of sugary, processed foods in schools and hospitals.

Not all of the group’s members are LCHF advocates, followers or even active members. Some members question LCHF science and raise concerns about weight regain on the diet. Even so, the sheer number of members suggests that Canada’s medical establishment is watching this trend with a keen eye.

“We have a saying: Once you see it, you can’t unsee it,” says Barbra Allen Bradshaw, describing what she sees as a benefit of the diet. Bradshaw, a pathologist in Abbotsford, B.C., is one of the site’s founders. “We didn’t know [these kinds of improvements] were possible because we didn’t know about this way of eating before,” she says.

Bradshaw and other LCHF supporters have launched a new organization,

Canadian Clinicians for Therapeutic Nutrition, that is made up of about 3,500 physicians and allied health providers who believe that

sugar, not fat, is the main driver of obesity and diabetes. They want to see Canada’s Food Guide include guidelines that favour fewer carbs and more fats. Some physicians go further and recommend LCHF diets s through weight-loss clinics and in medical visits, online forums and radio talk shows.

“We’re pushing forward, but we’re pushing against what’s currently in place,” says Berchuk. “We’re the early adopters, and we’re almost seen as heretics.”

This One Ingredient Swap Will Give Your Pancakes A Heart-Healthy Boost

This One Ingredient Swap Will Give Your Pancakes A Heart-Healthy Boost

Around the world, the theory that

sugar rather than fat is harming our bodies is gaining traction. Gary Taubes’ bestselling book

The Case Against Sugar meticulously lays out the argument that sugar is the root cause of obesity, diabetes, heart disease and hypertension. Over the past five years, the LCHF diet has been described in dozens of peer-reviewed scientific publications. Scroll through Twitter and you’ll find countless testaments from people around the world who swear that LCHF eating has changed their lives, from weight lost to autoimmune diseases cured to depression resolved. There are LCHF medical

conferences and

medical clinics,

TED Talks and

Caribbean cruises dedicated to this way of eating, a low-carb TV channel and even low-carb fast-food dining guides (KFC’s grilled chicken makes the cut, if you’re wondering).

It’s an appealing idea: Consume more fat, lose weight and gain all-around health benefits. What’s not to like?

The reality isn’t that simple, though. When it comes to diets, the line between scientific evidence and strongly held opinion is blurred. Despite all the before-and-after selfies hashtagged

#keto, there is still not a single study that shows conclusively that the majority of people who follow this diet will experience sustained weight loss beyond two years, compared with low-fat diets.

Diets are an emotional, touchy subject. Dieting is about food, yes, but also so much more: success and failure, as well as status, bias,

perception and self-esteem. Women experience so much shame related to their body image that researchers have developed a scale just to measure it: the Body Image Shame Scale. No matter where you look, the overall message is the same: Eat poorly and you’ve failed; eat well and you’re a star. But the definition of what it means to “eat poorly” or to “eat well” seems to be ever changing.

“Diet culture is tricky because the diet industry knows that diets aren’t cool anymore, so now it’s turned into a lifestyle change or a food lifestyle,” says Vincci Tsui, a registered dietitian in Calgary who specializes in working with clients with eating disorders.

To Tsui, LCHF is the latest manifestation of diet culture. “We live in a society that really upholds a certain type of body: a thin, athletic, able body. There is a status to that type of body. There are so many people who think that if you lose weight, then something is going right. I wish people could take a step back and be critical about why their body size is so important to them.”

Can Changing What Foods You Eat Improve Your Mental Health?

Can Changing What Foods You Eat Improve Your Mental Health?One thing is clear: It’s no longer in vogue to talk about size, scales or bikini bodies. Strong is the new skinny, as 1.5 million Instagram

hashtags proclaim. We don’t admit to dieting to look svelte in a bathing suit, à la Special K commercials of the 1990s. Instead, we put coconut oil in coffee and call it bio-hacking. We eliminate groups of foods from our diet and refer to it as detoxing. We proclaim that we eat healthy to be role models for our kids, reduce our risk of disease and have more energy.

But we still live in a thriving diet culture that rewards losing weight — it’s just packaged a little differently than before.

***

LCHF diets cover a spectrum. On one end, there’s what Berchuk calls the “modified Mediterranean diet,” which is plenty of vegetables, healthy fats and fish but less bread and pulses than the traditional approach. On the other extreme is the ketogenic diet. Diet Doctor, a website founded in 2011 by Swedish family doctor Andreas Eenfeldt and now the world’s biggest MD-driven “keto” site, terms it the “supercharged” version of low-carb eating. Keto is the current It diet, praised by svelte celebrities like Halle Berry and the raison d’être for some of the hottest cookbooks on the market.

Keto followers abstain from carbs, including most fruits (berries sometimes get a pass), to the point where they often get something called the “keto flu” in the first week — a fog of headaches, fatigue and irritability. The body, lacking the glucose it ordinarily gets through carbohydrates, goes through something called ketogenesis: Our livers begin to generate ketone bodies, or ketones, from fat. Proponents say that this accelerates fat burning.

In earlier incarnations of low-carb diets, followers replaced carbs with protein. But keto devotees rely more heavily on fat, deriving as much as 90 percent of their calories from it. Fat, they point out, is satiating — there’s no returning to the cupboard for a snack an hour after you eat. Many followers of keto intermittently fast, going 16 hours or more without food — like Berchuk when she skips breakfast — because of the belief that fat burning accelerates in a fasting state.

This Nutrient-Packed Ingredient Tastes As Good As Parmesan But Has Loads Of Health Benefits

This Nutrient-Packed Ingredient Tastes As Good As Parmesan But Has Loads Of Health Benefits

Forty-five-year-old Berchuk is well versed in the ups and downs of diets: She has been a yo-yo dieter most of her life. In the fall of 2016, she was cycling through Italy but stressing about her weight. She read a book called Sugar Free and was struck by a list of behaviours described as signs of an addiction to sugar, including obsessive thoughts about sugar and carbs, dishonesty about consumption of them, shame and guilt around food and preoccupation with body image. She had every one of them, she says. By the time she flew home from the land of pizza and pasta, she was committed to trying a low-carb, higher-fat diet.

That’s when she discovered the Facebook group. She has since become an ardent advocate of the LCHF way of eating and is studying to become board certified in obesity medicine. “I want to become an expert in obesity so that when I’m trying to convince stakeholders that we need to study this, I have some credibility,” she says. “I don’t want it to be just my own anecdote to say this works. I want expertise in this area.”

Bradshaw was diagnosed with

gestational diabetes when she was pregnant with her third child at 41 and came across research that suggests that low-carbohydrate eating could help manage her blood sugar. She decided that’s what she would do, but her local diabetes education centre disapproved of her approach. It advised her to eat about 165 grams of carbs each day — that’s generally considered to be a low amount, but among most low-carb devotees, it registers as high. (A keto low-carb diet recommends under 20 to 30 grams of net carbs, or approximately one large potato or half of a hamburger bun, depending on your weight and activity level.)

After her child was born, Bradshaw returned to her normal diet of pastas, veggies, proteins and some processed foods for a few months, but couldn’t lose weight. She switched back to a diet without much bread, pasta, fruit or processed food. In a year, she lost 22 pounds.

The closed Facebook group has never been advertised — membership spread by word of mouth. In the beginning, it was mostly physicians looking to manage weight and metabolic issues, often after pregnancy. Now, members seek support and recipes and exchange virtual high-fives when someone hits a goal weight. They discuss the pushback they get from colleagues. One expressed frustration when a general practitioner advised a family member, who’d lost weight on an LCHF diet but experienced a rise in cholesterol, to stop the diet and start taking a statin.

Over time, members have become vocal advocates for the LCHF approach, sharing ideas on how to take on the high-carb, processed-food environment we live in. Bradshaw has led campaigns to pull chocolate milk and sugary treats from her kids’ schools, and she and a colleague recently met with Health Canada representatives to discuss concerns about Canada’s Food Guide. They often point out the relationship between guidelines and food manufacturers, arguing that food companies pay for and publicize research that supports their products, flimsy though the research may be.

“It’s become a grassroots entity where things are happening from the bottom up, and we’re trying to push the change upward,” says Bradshaw.

Carolyn Snider, an emergency physician in Winnipeg who follows a low-carb diet, often advises patients to

cut down on their sugar intake. It’s not traditional advice given in the emergency department, but “nutrition often contributes to the reason why a patient may be in the emergency department,” Snider argues. “I feel a responsibility to make suggestions on potential changes, just as if they were to come in having been in a car crash and not wearing their seat belt. I have a responsibility to talk about not wearing a seat belt.”

Snider, who has a master’s in public health, doesn’t consider LCHF to be a fad diet. Like all the experts I spoke with, she doesn’t believe that one diet is right for everyone, but she does think that LCHF may be the right diet for some people. “In the medical community, we don’t believe there’s one type of hypertensive for people with high blood pressure or one type of chemotherapy for people with cancer,” she says, “so I’m not sure why there’s an insistence on only one right way to eat.”

Calgary family doctor Michelle Klassen became interested in LCHF after another physician raised the topic at a professional meeting. Klassen reviewed the published medical literature and found the evidence “compelling” enough to recommend an LCHF diet to her patients.

Based on what she found, Klassen started a dedicated weight and metabolic management program for her patients with insulin resistance. She offers group medical appointments in which patients are counselled to avoid sugars, eat natural fat and partake in intermittent fasting if it works for them. Patients may use all or a combination of those tools to help attain and maintain their health. The program is part food education, part cognitive therapy, says Klassen.

Some physicians are reticent to speak on the record about their interest in LCHF, concerned that their take on the science surrounding LCHF diets runs counter to Canada’s Food Guide and the conventional low-fat approach. “Everybody is worried that we’re going to get in trouble with our licensing bodies because this isn’t the mainstream,” says Berchuk.

How Do I Know If I Need To Lose Weight For My Health?

In Canada and elsewhere, LCHF-advocating physicians have been reported to their professional bodies because of their comments. In two high-profile cases, South African doctor Tim Noakes and Australian orthopedic surgeon Gary Fettle have been investigated for offering “medical advice” that favours LCHF diets. Last fall, Quebec family physician Evelyne Bourdua-Roy was reported to her provincial body after comments she made on a radio talk show were reported as medical “advice.” (Bourdua-Roy was not available for an interview for this article.)

The LCHF way of eating doesn’t align with the current

Canada’s Food Guide, which is endorsed by Health Canada but roundly criticized by experts in obesity. The guide recommends that women aged 19 to 50 eat six to seven servings of grain products a day and seven to eight servings of fruit and vegetables, and it recommends lower-fat milk alternatives. Following the tips in the food guide will, according to the guide, “reduce your risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, certain types of cancer and osteoporosis.”

Health Canada is expected to release a long-awaited updated food guide later this year. The main principles for the new guide, which were released in 2017, emphasize more plant-based foods and call for a reduction in processed and prepared foods that are high in sodium, sugar and saturated fat. These changes would direct Canadians to eat more fibre-rich foods and less red meat and replace the mostly saturated fats we consume, such as cream, high-fat cheese and butter, with unsaturated fats in the form of nuts, seeds and avocado.

***

Every day, another nutrition study is reported, often contradicting a report from not long before: You’ll live longer on a vegan diet! You’ll lose weight faster by eating meat! Meat causes cancer! Chocolate is good for you! Chocolate makers paid for the chocolate studies! It’s a dizzying parade of anecdotes presented as conclusions — a way of selling hope to people who despair over their weight.

As a society, despite the recent rise in body-positivity messaging, we still applaud weight loss as a testament of willpower and commitment and view anyone without a normal or low body mass index (BMI) as less worthy of a job or less attractive. This has been borne out in studies. The prevalence of obesity stigma is comparable to rates of racial discrimination, especially among women.

Our angst over food and weight plays out in

eating disorders, reported in between one and 3.5 percent of women. But those statistics probably woefully underestimate their true prevalence. A telling statistic about women’s relationship with food comes from a 2008 survey by

Self magazine, in which 65 percent of women said they were disordered eaters.

And if you’ll pardon yet another anecdote from the front lines of dieting: I almost died from an eating disorder two decades ago. I will attest despair is not too strong a word to describe our relationship to our food.

In this food environment, people frantically chase fad diets, seduced by the latest studies and testaments from people who attest that this will be different: “This is what worked for me.”

Physicians, too, are looking for answers. They acknowledge that the current advice given to people who are looking to lose weight is not sufficient in an environment that pounds us with highly processed food at every turn. Over a 39-year period, the prevalence of

obesity in Canadian adultsincreased from 10 to 26 percent. Among children, obesity has tripled since 1981. Obesity now accounts for

$3.9 billion in direct health care costs and $3.2 billion in indirect costs.

With

nearly half of Canadian women and two-thirds of Canadian men facing increased health risks from excess weight, plenty of experts acknowledge that the status quo is not working. “The likelihood of obesity going away on its own is low, and I think the world is recognizing that,” says Yoni Freedhoff, an Ottawa bariatric physician who wrote

The Diet Fix. In the book, he argues that people lose weight successfully when they take the suffering out of dieting. If a diet isn’t sustainable, the weight loss won’t be sustainable. Freedhoff doesn’t diss low-carb diets — they often work well in the short term, he says. But they are not commonly sustainable in the long term.

If we’re going to change the trajectory of obesity and related illnesses in Canada, it won’t be accomplished by a diet, says Freedhoff. Our relationship with food has changed dramatically in the past 40 years — the way we use food, the way food is marketed and engineered, portion sizes and the ubiquity of food at all social gatherings. “These are the things that need to change if we’re to break out of the cycle of dieting,” he says.

For the vast majority of people, attempts at weight loss don’t work in the long run. In fact, the more times a person attempts to lose weight with an unsustainable diet, the more likely they are to gain weight in the end.“I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with weight gain, but if a diet tends to produce the opposite effect of what you want it to do, then why are you still doing it?” asks Tsui.

10 Foods That Can Help Fight Dementia

10 Foods That Can Help Fight Dementia

***

The LCHF diet — even its keto extreme — isn’t a totally new idea. A version of the keto diet has been around as a

treatment for kids with epilepsy since the 1920s, after reports that the absence of food — starvation for two or three days — helped control seizures. In the past 20 years, it has once again gained in popularity as a treatment for epilepsy. Mayo Clinic researchers proposed that the benefits of fasting could be obtained through a ketogenic diet. Almost every textbook on epilepsy in children published between 1941 and 1980 reports on ketogenic diets.

Support for ketogenic eating is also growing in the diabetic community. A 2017 study in the journal

Nature showed that people who had pre-diabetes or type 2 diabetes and followed a ketogenic diet lost more weight and had greater reductions in medication needs than people who followed a low-fat, low-calorie diet.

But when it comes to weight loss, conclusive evidence that an LCHF approach is better than low-fat and low-calorie diets in the long term doesn’t yet exist. Neither is there conclusive evidence that an LCHF approach is harmful. A large, much-anticipated trial, published in the

Journal of the American Medical Association this winter, showed that people experienced no difference in weight loss by eating low-fat or low-carb, provided that they limited their intake of added sugars, refined carbs and highly processed foods.

‘I Can’t Magically Shrink Myself To Accommodate Others.’ Why I Called Out A Fat-Shamer On A FlightKevin Hall, a Canadian researcher who has led some of the most robust studies of low-carb versus low-fat eating at the National Institutes of Health in the United States, says that many fantastic claims made about keto diets — easy weight loss, better mental clarity, reduced depression — aren’t borne out by research. That said, “there doesn’t seem to be any huge problem with the things people used to be very concerned about [with low-carb diets], such as the dangerous effects of fat on cholesterol.”

Shahzadi Devje, a registered dietitian and certified diabetes educator in Toronto, says that larger, longer and higher-quality studies of LCHF are needed before she would recommend the diet. She tells her patients that short-term studies in small population groups show that the keto diet can help with weight loss in the first year, after which weight loss seems to plateau. She also notes the side effects (fatigue, headaches, brain fog and bad breath). Devje also warns that an overall uptick in fat intake may mean that you’re getting more trans and saturated fats, which may increase the risk of heart disease for some people. “I don’t have a sexy message for you but to say that evidence is lacking,” says Devje.

She counsels patients to focus on eating whole foods and plants and consider a food’s quality rather than its macronutrients. Eat healthy fats like nuts, avocados and olive oil, she says, but also eat legumes, lentils, starchy vegetables and whole grains. “A successful diet allows for the pleasure of eating,” she says. “That’s why it’s sustainable. People can incorporate it into their daily lives and see improvements in their blood sugar control. For me, a diet is a way of life.”

In Calgary, Klassen and Berchuk are trying to get a study under way to look at patients who go on LCHF diets prior to surgery. “We feel quite passionate about this because it’s worked for us,” says Berchuk. “It’s all anecdotal, but enough anecdote finally builds a case.”

It worked for them. Only time will tell if this is the diet that will work for people who are struggling to lose weight and keep it off. History suggests a healthy dose of skepticism may be in order.

This story was originally published on May 30, 2018 and updated on June 4.