Hiragana

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

| Hiragana ひらがな | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Japanese and Okinawan |

Time period

| ~800 AD to the present |

Parent systems

| |

Sister systems

| Katakana, Hentaigana |

| ISO 15924 | Hira, 410 |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

Unicode alias

| Hiragana |

| U+3040-U+309F, U+1B000-U+1B0FF | |

|

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Romanization |

Hiragana (平仮名, ひらがな?) is a Japanese syllabary, one basic component of the Japanese writing system, along with katakana, kanji, and in some cases rōmaji (theLatin-script alphabet). The word hiragana means "ordinary syllabic script".

Hiragana and katakana are both kana systems. Each sound in the Japanese language (strictly, each mora) is represented by one or two characters in each system. This may be either a vowel such as "a" (hiragana あ); a consonant followed by a vowel such as "ka" (か); or "n" (ん), a nasal sonorant which, depending on the context, sounds either like English m, n, or ng ([ŋ]), or like the nasal vowels of French. Because the characters of the kana do not represent single consonants (except in the case of ん "n"), the kana are referred to as syllabaries and not alphabets.[1]

Hiragana is used to write native words for which there are no kanji, including grammatical particles such as から kara "from", and suffixes such as さん ~san "Mr., Mrs., Miss, Ms." Likewise, hiragana is used to write words whose kanji form is obscure, not known to the writer or readers, or too formal for the writing purpose. There is also some flexibility for words that have common kanji renditions to be optionally written instead in hiragana, according to an individual author's preference. Verb and adjective inflections, as, for example, be-ma-shi-ta (べました) in tabemashita (食べました?, "ate"), are written in hiragana, often following a verb or adjective root (here, "食") that is written in kanji. When Hiragana is used to show the pronunciation of kanji characters as reading aid, it is referred to as furigana. The article Japanese writing system discusses in detail how the various systems of writing are used.

There are two main systems of ordering hiragana: the old-fashioned iroha ordering and the more prevalent gojūon ordering.

Contents

[hide]Writing system[edit]

| a | i | u | e | o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∅ | あ | い | う | え | お |

| k | か | き | く | け | こ |

| s | さ | し | す | せ | そ |

| t | た | ち | つ | て | と |

| n | な | に | ぬ | ね | の |

| h | は | ひ | ふ | へ | ほ |

| m | ま | み | む | め | も |

| y | や | ゆ | よ | ||

| r | ら | り | る | れ | ろ |

| w | わ | ゐ | ゑ | を | |

| ん (N) | |||||

| Functional marks and diacritics | |||||

| っ | ゝ | ゛ | ゜ | ||

The modern hiragana syllabary consists of 46 characters:

- 5 singular vowels

- Notionally, 45 consonant–vowel unions, consisting of 9 consonants in combination with each of the 5 vowels, of which:

- 3 (yi, ye, and wu) are unused

- 2 (wi, and we) are obsolete in modern Japanese

- 1 (wo) is usually pronounced as a vowel (o) in modern Japanese, and is preserved in only one use, as a particle

- 1 singular consonant

These are conceived as a 5×10 grid (gojūon, 五十音, lit. "Fifty Sounds"), as illustrated in the adjacent table, with the extra character being the anomalous singular consonant ん (N).

Romanisation of the kana does not always strictly follow the consonant-vowel scheme laid out in the table. For example, ち, nominally ti, is very often romanised as chi in an attempt to better represent the actual sound in Japanese.

These basic characters can be modified in various ways. By adding a dakuten marker ( ゛), a voiceless consonant is turned into a voiced consonant: k→g,ts/s→z, t→d, h→b and ch/sh→j. Hiragana beginning with an h can also add a handakuten marker ( ゜) changing the h to a p.

A small version of the hiragana for ya, yu or yo (ゃ, ゅ or ょ respectively) may be added to hiragana ending in i. This changes the i vowel sound to a glide (palatalization) to a, u or o. Addition of the small y kana is called yōon. For example, き (ki) plus ゃ (small ya) becomes きゃ (kya).

A small tsu っ, called a sokuon, indicates that the following consonant is geminated (doubled). For example, compare さか saka "hill" with さっか sakka"author". It also sometimes appears at the end of utterances, where it denotes a glottal stop, as in いてっ! ([iteʔ] Ouch!). However, it cannot be used to double the na, ni, nu, ne, no syllables' consonants – to double them, the singular n (ん) is added in front of the syllable.

Hiragana usually spells long vowels with the addition of a second vowel kana. The chōonpu (long vowel mark) (ー) used in katakana is rarely used with hiragana, for example in the word らーめん, rāmen, but this usage is considered non-standard. In informal writing, small versions of the five vowel kana are sometimes used to represent trailing off sounds (はぁ haa, ねぇ nee). Standard and voiced iteration marks are written in hiragana as ゝ and ゞ respectively.

Table of hiragana[edit]

The following table shows the complete hiragana together with the Hepburn romanization and IPA transcription in the gojūon order. Hiragana with dakuten or handakuten follow the gojūon kana without them, with theyōon kana following. Obsolete and normally unused kana are shown in gray. For all syllables besides ん, the pronunciation indicated is for word-initial syllables, for mid-word pronunciations see below.

| Monographs (gojūon) | Digraphs (yōon) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | i | u | e | o | ya | yu | yo | |

| ∅ | あ a [a] | い i [i] | う u [u͍] | え e [e] | お o [o] | |||

| K | か ka [ka] | き ki [ki] | く ku [ku͍] | け ke [ke] | こ ko [ko] | きゃ kya [kʲa] | きゅ kyu [kʲu͍] | きょ kyo [kʲo] |

| S | さ sa [sa] | し shi [ɕi] | す su [su͍] | せ se [se] | そ so [so] | しゃ sha [ɕa] | しゅ shu [ɕu͍] | しょ sho [ɕo] |

| T | た ta [ta] | ち chi [ t͡ɕi] | つ tsu [ t͡su͍] | て te [te] | と to [to] | ちゃ cha [ t͡ɕa] | ちゅ chu [ t͡ɕu͍] | ちょ cho [ t͡ɕo] |

| N | な na [na] | に ni [ni] | ぬ nu [nu͍] | ね ne [ne] | の no [no] | にゃ nya [nʲa] | にゅ nyu [nʲu͍] | にょ nyo [nʲo] |

| H | は ha [ha] ([w͍a] as particle) | ひ hi [çi] | ふ fu [ɸu͍] | へ he [he] ([e] as particle) | ほ ho [ho] | ひゃ hya [ça] | ひゅ hyu [çu͍] | ひょ hyo [ço] |

| M | ま ma [ma] | み mi [mi] | む mu [mu͍] | め me [me] | も mo [mo] | みゃ mya [mʲa] | みゅ myu [mʲu͍] | みょ myo [mʲo] |

| Y | や ya [ja] | ゆ yu [ju͍] | よ yo [jo] | |||||

| R | ら ra [ɽa] | り ri [ɽi] | る ru [ɽu͍] | れ re [ɽe] | ろ ro [ɽo] | りゃ rya [ɽʲa] | りゅ ryu [ɽʲu͍] | りょ ryo [ɽʲo] |

| W | わ wa [w͍a] | ゐ i/wi [(w͍)i] | ゑ e/we [(w͍)e] | を o/wo [(w͍)o] (particle) | ||||

| * | ん n [n] [m] [ŋ] before stop consonants; [ɴ] [ũ͍] [ĩ] elsewhere | っ (indicates a geminateconsonant) | ゝ (reduplicates and unvoices syllable) | ゞ (reduplicates and voices syllable) | ||||

| Diacritics (gojūon with (han)dakuten) | Digraphs with diacritics (yōon with (han)dakuten) | |||||||

| a | i | u | e | o | ya | yu | yo | |

| G | が ga [ɡa] | ぎ gi [ɡi] | ぐ gu [ɡu͍] | げ ge [ɡe] | ご go [ɡo] | ぎゃ gya [ɡʲa] | ぎゅ gyu [ɡʲu͍] | ぎょ gyo [ɡʲo] |

| Z | ざ za [za] | じ ji [d͡ʑi] | ず zu [zu͍] | ぜ ze [ze] | ぞ zo [zo] | じゃ ja [d͡ʑa] | じゅ ju [d͡ʑu͍] | じょ jo [d͡ʑo] |

| D | だ da [da] | ぢ ji [d͡ʑi] | づ zu [zu͍] | で de [de] | ど do [do] | ぢゃ ja [d͡ʑa] | ぢゅ ju [d͡ʑu͍] | ぢょ jo [d͡ʑo] |

| B | ば ba [ba] | び bi [bi] | ぶ bu [bu͍] | べ be [be] | ぼ bo [bo] | びゃ bya [bʲa] | びゅ byu [bʲu͍] | びょ byo [bʲo] |

| P | ぱ pa [pa] | ぴ pi [pi] | ぷ pu [pu͍] | ぺ pe [pe] | ぽ po [po] | ぴゃ pya [pʲa] | ぴゅ pyu [pʲu͍] | ぴょ pyo [pʲo] |

| V | ゔ vu/u [v(u͍)] | |||||||

In the middle of words, the g sound (normally [ɡ]) often turns into a velar nasal [ŋ] and less often (although increasing recently) into the voiced velar fricative [ɣ]. An exception to this is numerals; 15 juugo is considered to be one word, but is pronounced as if it was jū and go stacked end to end: [d͡ʑu͍ːɡo].

Additionally, the j sound (normally [d͡ʑ]) can be pronounced [ʑ] in the middle of words. For example すうじ sūji [su͍ːʑi] 'number'.

In archaic forms of Japanese, there existed the kwa (くゎ [kʷa]) and gwa (ぐゎ [ɡʷa]) digraphs. In modern Japanese, these phonemes have been phased out of usage and only exist in the extended katakana digraphs for approximating foreign language words.

The singular n is pronounced [n] before t, ch, ts, n, r, z, j and d, [m] before m, b and p, [ŋ] before k and g, [ɴ] at the end of utterances, [ũ͍] before vowels, palatal approximants (y), consonants s, sh, h, f and w, and finally [ĩ] after the vowel i if another vowel, palatal approximant or consonant s, sh, h, f or w follows.

In kanji readings, the diphthongs ou and ei are today usually pronounced [oː] (long o) and [eː] (long e) respectively. For example とうきょう (lit. toukyou) is pronounced [toːkʲoː] 'Tokyo', and せんせい sensei is [seũ͍seː]'teacher'. However, とう tou is pronounced [tou͍] 'to inquire', because the o and u are considered distinct, u being the infinitive verb ending. Similarly, している shite iru is pronounced [ɕiteiɾu͍] 'is doing'.

For a more thorough discussion on the sounds of Japanese, please refer to Japanese phonology.

Spelling rules[edit]

With a few exceptions for sentence particles は, を, and へ (pronounced as wa, o, and e), and a few other arbitrary rules, Japanese, when written in kana, is phonemically orthographic, i.e. there is a one-to-one correspondence between kana characters and sounds, leaving only words' pitch accent unrepresented. This has not always been the case: a previous system of spelling, now referred to as historical kana usage, differed substantially from pronunciation; the three above-mentioned exceptions in modern usage are the legacy of that system. The old spelling is referred to as kanazukai (仮名遣い?).

There are two hiragana pronounced ji (じ and ぢ) and two hiragana pronounced zu (ず and づ), but to distinguish them, sometimes ぢ is written as di and づ is written as dzu. These pairs are not interchangeable. Usually, ji is written as じ and zu is written as ず. There are some exceptions. If the first two syllables of a word consist of one syllable without a dakuten and the same syllable with a dakuten, the same hiragana is used to write the sounds. For example chijimeru ('to boil down' or 'to shrink') is spelled ちぢめる and tsudzuku ('to continue') is つづく. For compound words where the dakuten reflects rendaku voicing, the original hiragana is used. For example, chi (血 'blood') is spelled ち in plain hiragana. When 鼻 hana ('nose') and 血 chi ('blood') combine to make hanaji 鼻血 'nose bleed'), the sound of 血 changes from chi to dji. So hanadjiis spelled はなぢ according to ち: the basic hiragana used to transcribe 血. Similarly, tsukau (使う/遣う; 'to use') is spelled つかう in hiragana, so kanazukai (仮名遣い; 'kana use', or 'kana orthography') is spelledかなづかい in hiragana.

However, this does not apply when kanji are used phonetically to write words which do not relate directly to the meaning of the kanji (see also ateji). The Japanese word for 'lightning', for example, is inazuma (稲妻). The 稲 component means 'rice plant', is written いな in hiragana and is pronounced: ina. The 妻 component means 'wife' and is pronounced tsuma (つま) when written in isolation—or frequently as zuma (ずま) when it features after another syllable. Neither of these components have anything to do with 'lightning', but together they do when they compose the word for 'lightning'. In this case, the default spelling in hiraganaいなずま rather than いなづま is used.

Officially, ぢ and づ do not occur word-initially pursuant to modern spelling rules. There were words such as ぢばん jiban 'ground' in the historical kana usage, but they were unified under じ in the modern kana usagein 1946, so today it is spelled exclusively じばん. However, づら zura 'wig' (from かつら katsura) and づけ zuke (a sushi term for lean tuna soaked in soy sauce) are examples of word-initial づ today. Some people write the word for hemorrhoids as ぢ (normally じ) for emphasis.

No standard Japanese words begin with the kana ん (n). This is the basis of the word game shiritori. ん n is normally treated as its own syllable and is separate from the other n-based kana (na, ni etc.). A notable exception to this[clarification needed] is the colloquial negative verb conjugation; for example わからない wakaranai meaning "[I] don't understand" is rendered as わからん wakaran. It is however not a contraction of the former, but instead comes from the classic negative verb conjugation ぬ nu (わからぬ wakaranu).

ん is sometimes directly followed by a vowel (a, i, u, e or o) or a palatal approximant (ya, yu or yo). These are clearly distinct from the na, ni etc. syllables, and there are minimal pairs such as きんえん kin'en 'smoking forbidden', きねん kinen 'commemoration', きんねん kinnen 'recent years'. In Hepburn romanization, they are distinguished with an apostrophe, but not all romanization methods make the distinction. For example past prime minister Junichiro Koizumi's first name is actually じゅんいちろう Jun'ichirō pronounced [d͡ʑu͍ũ͍it͡ɕiɾoː]

There are a few hiragana which are rarely used. ゐ wi and ゑ we are obsolete outside of Okinawan dialects. ゔ vu is a modern addition used to represent the /v/ sound in foreign languages such as English, but since Japanese from a phonological standpoint does not have a /v/ sound, it is pronounced as /b/ and mostly serves as a more accurate indicator of a word's pronunciation in its original language. However, it is rarely seen because loanwords and transliterated words are usually written in katakana, where the corresponding character would be written as ヴ. ぢゃ, ぢゅ, ぢょ for ja/ju/jo are theoretically possible in rendaku, but are practically never used. For example 日本中 'throughout Japan' could be written にほんぢゅう, but is practically always にほんじゅう.

The みゅ myu kana is extremely rare in originally Japanese words; linguist Haruhiko Kindaichi raises the example of the Japanese family name Omamyūda (小豆生田) and claims it is the only occurrence amongst pure Japanese words. Its katakana counterpart is used in many loanwords, however.

History[edit]

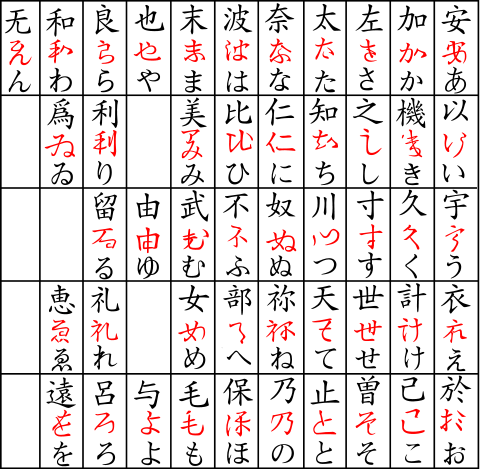

Hiragana developed from man'yōgana, Chinese characters used for their pronunciations, a practice which started in the 5th century.[2] The oldest example of Man'yōgana isInariyama Sword which is an iron sword excavated at the Inariyama Kofun in 1968. This sword is thought to be made in year of 辛亥年 (which is A.D. 471 in commonly accepted theory).[3] The forms of the hiragana originate from the cursive script style of Chinese calligraphy. The figure below shows the derivation of hiragana from manyōgana via cursive script. The upper part shows the character in the regular script form, the center character in red shows the cursive script form of the character, and the bottom shows the equivalent hiragana. Note also that the cursive script forms are not strictly confined to those in the illustration.

When they were first developed, hiragana were not accepted by everyone. The educated or elites preferred to use only the kanji system. Historically, in Japan, the regular script (kaisho) form of the characters was used by men and called otokode(男手?), "men's writing", while the cursive script (sōsho) form of the kanji was used by women. Hence hiragana first gained popularity among women, who were generally not allowed access to the same levels of education as men. And thus hiragana was first widely used among court women in the writing of personal communications and literature.[4] From this comes the alternative name of onnade (女手?) "women's writing".[5] For example, The Tale of Genji and other early novels by female authors used hiragana extensively or exclusively.

Male authors came to write literature using hiragana. Hiragana was used for unofficial writing such as personal letters, while katakana and Chinese were used for official documents. In modern times, the usage of hiragana has become mixed withkatakana writing. Katakana is now relegated to special uses such as recently borrowed words (i.e., since the 19th century), names in transliteration, the names of animals, in telegrams, and for emphasis.

Originally, for all syllables there was more than one possible hiragana. In 1900, the system was simplified so each syllable had only one hiragana. The deprecated hiragana are now known as hentaigana (変体仮名?).

The pangram poem Iroha-uta ("ABC song/poem"), which dates to the 10th century, uses every hiragana once (except n ん, which was just a variant of む before Muromachi era).

Stroke order and direction[edit]

The following table shows the method for writing each hiragana character. It is arranged in the traditional way, beginning top right and reading columns down. The numbers and arrows indicate the stroke order and direction respectively.

Unicode[edit]

Main articles: Hiragana (Unicode block) and Kana Supplement (Unicode block)

Hiragana was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 1991 with the release of version 1.0.

The Unicode block for Hiragana is U+3040–U+309F:

| Hiragana[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+304x | ぁ | あ | ぃ | い | ぅ | う | ぇ | え | ぉ | お | か | が | き | ぎ | く | |

| U+305x | ぐ | け | げ | こ | ご | さ | ざ | し | じ | す | ず | せ | ぜ | そ | ぞ | た |

| U+306x | だ | ち | ぢ | っ | つ | づ | て | で | と | ど | な | に | ぬ | ね | の | は |

| U+307x | ば | ぱ | ひ | び | ぴ | ふ | ぶ | ぷ | へ | べ | ぺ | ほ | ぼ | ぽ | ま | み |

| U+308x | む | め | も | ゃ | や | ゅ | ゆ | ょ | よ | ら | り | る | れ | ろ | ゎ | わ |

| U+309x | ゐ | ゑ | を | ん | ゔ | ゕ | ゖ | ゙ | ゚ | ゛ | ゜ | ゝ | ゞ | ゟ | ||

| Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

The Unicode hiragana block contains precomposed characters for all hiragana in the modern set, including small vowels and yōon kana for compound syllables, plus the archaic ゐ wi and ゑ we and the rare ゔ vu; the archaic 𛀁 ye is included in plane 1 at U+1B001 (see below). All combinations of hiragana with dakuten and handakuten used in modern Japanese are available as precomposed characters, and can also be produced by using a base hiragana followed by the combining dakuten and handakuten characters (U+3099 and U+309A, respectively). This method is used to add the diacritics to kana that are not normally used with them, for example applying the dakuten to a pure vowel or the handakuten to a kana not in the h-group.

Characters U+3095 and U+3096 are small か (ka) and small け (ke), respectively. U+309F is a ligature of より (yori) occasionally used in vertical text. U+309B and U+309C are spacing (non-combining) equivalents to the combining dakuten and handakuten characters, respectively.

Historic and variant forms of Japanese kana characters were added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2010 with the release of version 6.0.

The Unicode block for Kana Supplement is U+1B000–U+1B0FF:

| Kana Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1B00x | 𛀀 | 𛀁 | ||||||||||||||

| U+1B01x | ||||||||||||||||

| ... | (omitted; not used yet) | |||||||||||||||

| U+1B0Fx | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes

| ||||||||||||||||