When the Emperor Was Divine

(Redirected from When the Emperor was Divine)

The 2003 edition cover

| |

| Author | Julie Otsuka |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Iris Weinstein |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

| Publisher | Alfred A. Knopf |

Publication date

| 2002 |

| Pages | 168 |

| ISBN | 978-0-385-72181-3 |

When the Emperor was Divine is a historical fiction novel written by American author Julie Otsuka about a Japanese American family sent to an internment camp in the Utah desert during World War II. The novel, loosely based on the wartime experiences of Otsuka's mother's family,[1] is written through the perspective of four family members, detailing their eviction from California and their time in camp. It is Otsuka's debut novel, and was published in the United States in 2002 by Alfred A. Knopf.

Character List[edit]

- Mother: The first section of the novel follows her perspective. She is calm and cool despite the drastic change in her life and ends up becoming the bread winner for her family after the internment camp.

- Daughter: She is 11 years old with long black hair. Daughter is very inquisitive and can easily make friends with strangers.

- Son: He is 8 years old and the one in the family who writes to their father the most. He also fantasizes about the supposed glory of his return more than other characters.

- Father: He is put in an internment camp before the rest of the family. Upon return from the camp he is listless and unable to return to the life he had before.

Plot[edit]

In "When the Emperor was Divine," Author Julie Otsuka gives a fictional retelling of the Japanese American experience during the Internment period of WWII. The story follows a Japanese American family; a father, a mother, a son, and a daughter. The family members remain nameless, thus giving their story a universal quality. The novel is divided into 5 sections, each told from a different family member's perspective. The first chapter, the mother's perspective, follows the family's preparations for leaving for the camp. The second chapter, from the girl's perspective, takes place on the train as the family is transported to their internment location. The third chapter, from the boy's perspective, chronicles the three years the family spends at the internment camp in Topaz, Utah. The fourth chapter, told from the combined perspectives of the boy and girl, tells of the family's return home and their efforts at rebuilding their lives as well as their experience in the post war milieu of anti-Japanese discrimination. The final chapter is a confession, told from the father's perspective and structured as a direct address to the reader.

Reception and awards[edit]

The book was met with a generally positive reception. Writing for The New York Times, literary critic Michiko Kakutani stated "though the book is flawed by a bluntly didactic conclusion, the earlier pages testify to the author's lyric gifts and narrative poise".[2] Sylvia Santiago of Herizons magazine described Otsuka's writing style as "scrupulously unsentimental", thus "creating a contrast to the sensitive subject matter".[3] O: The Oprah Magazine said the novel was "a meditation on what it means to be loyal to one's country and to one's self, and on the cost and the necessity of remaining brave and human".[4]

When the Emperor was Divine won the American Library Association's Alex Award in 2003 and also won an Asian American Literary Award.[5][6]

Julie Otsuka

Julie Otsuka

| |

|---|---|

| Born | May 15, 1962 Palo Alto, California |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Yale University Columbia University |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

| Notable works | When the Emperor was Divine The Buddha in the Attic |

| Relatives | Michael Otsuka |

| Website | |

| www | |

Julie Otsuka is an award-winning Japanese American author. Otsuka is known for her historical fiction novels dealing with Japanese Americans. Her books are known for calling attention to the plight of Japanese Americans throughout World War II. She did not live through the Japanese Internment period, but her mother, uncle, and two grandparents did, which gives Otsuka a unique and personal perspective on the matter. When the Emperor was Divine was the first fiction novel where she discusses Japanese internment camps. With a background as a painter, Julie Otsuka's attention to detail and great descriptions give the reader vivid imagery of different situations throughout her novels.[1] She is a recipient of the Albatros Literaturpreis.

Biography[edit]

Otsuka was born in 1962, in Palo Alto, California. Her father worked as an aerospace engineer, while her mother worked as a lab technician before she gave birth to Otsuka. Both of her parents were of Japanese descent, with her father being an issei and her mother being a nisei.[2] At the age of nine, her family moved to Palos Verdes, California. She has two brothers, one of whom, Michael Otsuka, is currently teaching at the London School of Economics.[3]

After graduating from high school, Otsuka attended Yale University, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1984. She later graduated from Columbia University with a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1999.[4][5] Her debut novel When the Emperor was Divine dealt with Japanese American internment during World War II. It was published in 2002 by Alfred A. Knopf. Her second novel, The Buddha in the Attic (2011), is about Japanese picture brides.

Otsuka lives in New York City.[6]

Awards and honors[edit]

- 2004 Guggenheim Fellowship[7]

- 2003 Asian American Literary Award, When the Emperor Was Divine[8]

- 2003 Alex Award, When the Emperor Was Divine[9]

- 2011 National Book Award, finalist, The Buddha in the Attic

- 2011 Los Angeles Times Book Prize, finalist, The Buddha in the Attic

- 2011 Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction, The Buddha in the Attic[10]

- 2011 New York Times and San Francisco Chronicle, bestseller, The Buddha in the Attic

- 2012 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, The Buddha in the Attic[11]

- 2012 American Academy of Arts and Letters "Arts and Letters Award in Literature"[12]

- 2012 Prix Femina Étranger, The Buddha in the Attic[13]

- 2014 Albatros Literaturpreis for Wovon wir träumten (The Buddha in the Attic) co-won with German translator Katja Scholtz.[14]

Works[edit]

- When the Emperor was Divine. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf. 2002. ISBN 978-0-385-72181-3.

A novel written by Julie Otsuka in 2002 describing a Japanese-American family that was put into an internment camp in the second World War. The novel follows a family made up of a mother, her two children and their father who was incarcerated and whose location is unknown until his return after the war. The novel depicts the struggle of Japanese-Americans at the time and the unimaginable life conditions that these people suffered during and after the internment period. The first three chapters are told in the perspective of the mother, the eleven-year-old daughter and the eight-year-old son. The fourth chapter is told through a "we" perspective that is an attempt to articulate the struggle to Japanese-Americans as a whole and the fifth giving the perspective of the family's father.

- The Buddha in the Attic. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf. 2011. ISBN 978-0-307-74442-5. (2013 England: ISBN 978-0-241-95648-9)

This novel is similar to When the Emperor was Divine in terms that both deal with the troubles of Japanese Americans living in a new land. They both confront the harsh reality that the American Dream is not something so easily attained. In 8 sections, this novel chronicles a few Japanese picture brides who are to be sent to the United States in order to get married. Despite dreaming of the wonderful life they will live in America, they are instead presented with a life of labor and discrimination. These hardships only get worse as The United States gets involved in World War II[1]

Japanese American history is the history of Japanese Americans or the history of ethnic Japanese in the United States. People from Japan began immigrating to the U.S. in significant numbers following the political, cultural, and social changes stemming from the 1868 Meiji Restoration. Large-scale Japanese immigration started with immigration to Hawaii during the first year of the Meiji period in 1868. Online

Contents

Timeline[edit]

Significant Japanese immigration to the United States did not begin until the late nineteenth century. However, there is evidence to suggest that the first Japanese individual to land in North America was a young boy accompanying Francisican friar, Martín Ignacio Loyola, in October 1587, whilst on Loyola’s second circumnavigation trip around the world. Japanese outcasts Oguri Jukichi[2] and Otokichi[3] are believed to be the first Japanese citizens to reach present day California in the early nineteenth century.[4] Anyhow, history of Japanese Americans is considered to have begun in the mid nineteenth century.

- 1841, June 27 Captain Whitfield, commanding a New England sailing vessel, rescues five shipwrecked Japanese sailors. Four disembark at Honolulu, however Manjiro Nakahama stays on board returning with Whitfield to Fairhaven, Massachusetts. After attending school in New England and adopting the name John Manjiro, he later became an interpreter for Commodore Matthew C. Perry.

- 1850: Seventeen survivors of a Japanese shipwreck are saved by the American freighter Auckland off the coast of California. In 1852, the group is sent to Macau to join Commodore Matthew C. Perry as a gesture to help open diplomatic relations with Japan. One of them, Joseph Heco (Hikozo Hamada), goes on to become the first Japanese person to become a naturalized American citizen.[5]

- 1861: The utopian minister Thomas Lake Harris of the Brotherhood of the New Life visits England, where he meets Nagasawa Kanaye, who becomes a convert. Nagasawa returns to the U.S. with Harris and follows him to Fountaingrove in Santa Rosa, California. When Harris leaves the Californian commune, Nagasawa became the leader and remained there until his death in 1932.[6]

- 1866: Japanese students arrive in the United States, supported by the Japan Mission of the Reformed Church in America which had opened in 1859 at Kanagawa.[7]

- 1869: A group of Japanese people arrive at Gold Hills, California and build the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony. Okei becomes the first recorded Japanese woman to die and be buried in the United States.

- 1882: The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This arguably left room for agricultural labour, encouraging immigration and recruitment of Japanese from both Hawaii and Japan[8]

- 1884: The Japanese grants passports for contract labour in Hawaii where there was a demand for cheap labour.[9]

- 1885: On February 8, the first official intake of Japanese migrants to a U.S.-controlled entity occurs when 676 men, 159 women, and 108 children arrive in Honolulu on board the Pacific Mail passenger freighter City of Tokio. These immigrants, the first of many Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, have come to work as laborers on the island's sugar plantations via an assisted passage scheme organized by the Hawaiian government.

- 1886': The Japanese government legalizes emigration

- 1893: The San Francisco Board of Education attempts to introduce segregation for Japanese American children, but withdraws the measure following protests by the Japanese government.

- 1900s: Japanese immigrants begin to lease land and sharecrop.

- 1902: Yone Noguchi publishes The American Diary of a Japanese Girl, the first Japanese American novel.

- 1903: In Yamataya v. Fisher (Japanese Immigrant Case) the Supreme Court held that Japanese Kaoru Yamataya was subject to deportation since her Fifth Amendments due process was not violated in regards to the appeals process of the 1891 Immigration Act. This allowed for individuals to challenge their deportation in the courts by challenging the legitimacy of the procedures.

- 1906: The San Francisco Board of Education successfully implements segregation for Asian students in public schools.[citation needed]

- 1907: The Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 between United States and Japan results in Japan ending the issuance passports for new laborers.

- 1908: Japanese "picture brides" enter the United States.

- 1913: The California Alien Land Law of 1913 bans Japanese from purchasing land; whites felt threatened by Japanese success in independent farming ventures.

- 1924: The federal Immigration Act of 1924 banned immigration from Japan.

- 1927: Kinjiro Matsudaira becomes the first Japanese American to be elected mayor of a U.S. city (town of Edmonston, Maryland).[10]

- 1930s: Issei become economically stable for the first time in California and Hawaiʻi.

- 1941: Attack on Pearl Harbor: Imperial Japanese forces attack the United States Navy base at Naval Station Pearl Harbor in Honolulu. Japanese community leaders are arrested and detained by federal authorities.

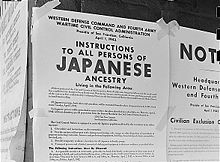

- 1942: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066 on February 19, beginning Japanese American internment. Over the course of the war, approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese who lived on the West Coast of the United States are uprooted from their homes and interned.

- 1942: Japanese American soldiers from Hawaiʻi form the 100th Infantry Battalion of the United States Army in June 1942. Subsequently, the battalion fights in Europe beginning in September 1943. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/100th%20Infantry%20Battalion/

- 1944: Ben Kuroki became the only Japanese-American in the U.S. Army Air Forces to serve in combat operations overseas, both in the European Theater, then in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II.

- 1944: The U.S. Army 100th Battalion merges with the all-volunteer Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team that was formed with men from Hawaii and the continental U.S. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/442nd%20Regimental%20Combat%20Team/

- 1945: Thirty thousand Japanese Americans were in Japan, unable to return to the United States since the nations were at war.[11]

- 1945: The only Nisei unit of the U.S. Army in Bavaria assists in both the liberation of some of the satellite camps of Dachau,[12] and by May 2, halts the Dachau-Austria death march, saving hundreds of prisoners.[13]

- 1945: By war's end, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team is awarded 18,143 decorations, including 9,486 Purple Hearts, becoming the most decorated military unit in United States history.

- 1959: Daniel K. Inouye is elected to the United States House of Representatives, becoming the first Japanese American to serve in Congress.

- 1962: Minoru Yamasaki is awarded the contract to design the World Trade Center, becoming the first Japanese American architect to design a supertall skyscraper in the United States.

- 1963: Daniel K. Inouye becomes the first Japanese American in the United States Senate.

- 1965: Patsy T. Mink becomes the first woman of color in Congress.

- 1971: Norman Y. Mineta is elected mayor of San Jose, California, becoming the first Asian American mayor of a major U.S. city.

- 1972: Robert A. Nakamura produces Manzanar, the first personal documentary about internment.

- 1974: George R. Ariyoshi becomes the first Japanese American governor in the State of Hawaiʻi.

- 1976: S. I. Hayakawa of California and Spark Matsunaga of Hawaiʻi become the second and third U.S. Senators of Japanese descent.

- 1978: Ellison S. Onizuka becomes the first Asian American astronaut. Onizuka was one of the seven astronauts to die in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986.

- 1980: Congress creates the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to investigate internment during World War II.

- 1980: Eunice Sato becomes the first Asian-American female mayor of a major American city when she was elected mayor of Long Beach, California.[14]

- 1983: The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians reports that Japanese-American internment was not justified by military necessity and that internment was based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." The Commission recommends an official Government apology; redress payments of $20,000 to each of the survivors; and a public education fund to help ensure that this would not happen again.

- 1988: President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, apologizing for Japanese-American internment and providing reparations of $20,000 to each victim.

- 1994: Mazie K. Hirono is elected Lieutenant Governor of Hawaii, becoming the first Japanese immigrant elected state lieutenant governor of a state. Hirono later is elected in the U.S. House of Representatives.

- 1996: A. Wallace Tashima is nominated to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and becomes the first Japanese American to serve as a judge of a United States court of appeals.

- 1998: Chris Tashima becomes the first U.S.-born Japanese American actor to win an Academy Award for his role in the film Visas and Virtue.

- 1999: U.S. Army General Eric Shinseki becomes the first Asian American to serve as chief of staff of a branch of the armed forces. Shinseki later serves as Secretary of Veterans Affairs (2009–2014).

- 2000: Norman Y. Mineta becomes the first Asian American appointed to the United States Cabinet. He serves as Secretary of Commerce from 2000–2001 and Secretary of Transportation from 2001–2006.

- 2010: Daniel K. Inouye becomes the highest ranking Asian American politician in U.S. history when he succeeds Robert Byrd as President pro tempore of the United States Senate.

Japanese American history before World War II[edit]

Immigration

Significant Japanese immigration to the United States did not begin until the late nineteenth century. However, there is evidence to suggest that the first Japanese individual to land in North America was a young boy accompanying Francisican friar, Martín Ignacio Loyola, in October 1587, whilst on Loyola’s second circumnavigation trip around the world. Japanese outcasts Oguri Jukichi and Otokichi are believed to be the first Japanese citizens to reach present day California in the early nineteenth century.[15]

Major Japanese immigration the U.S. only really began in 1853. This was due to the success of Commodore Matthew Perry’s expedition to Japan where he successfully negotiated a treaty opening Japan to American trade. Further developments included the start of direct shipping between San Francisco and Japan in 1855 and established official diplomatic relations in 1860.[16] Japanese immigration to the United States was mostly economically motivated. Stagnating economic conditions causing poor living conditions and high unemployment pushed Japanese people to search elsewhere for a better life. Japan’s population density had increased from 1,335 per square in 1872 to 1,885 in 1903 intensifying economic pressure on working class populations.[17] Rumours of better standards of living in the “land of promise” encouraged a rise in immigration to the U.S. Only fifty-five Japanese were censored living in the United States in 1870 however by 1890 there had been two thousand new arrivals. The numbers of new arrivals peaked in 1907 with as many as 30,000 Japanese immigrants counted (Economic and living conditions were particularly bad in Japan at this point as a result of the Russian-Japanese wars of 1904–5).[18] Japanese immigrants who moved to mainland U.S. settled on the West Coast primarily in California.[19]

Nonetheless, there was a history of legalized discrimination in American immigration laws which heavily restricted Japanese immigration. The Naturalization Act of 1790 specified naturalization of 'any alien, being a free white person', and this was interpreted to prohibit Chinese immigrants from being American citizens. Japanese immigrants were exempt from the interpretation of this legislation. However, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had a more significant impact on Japanese immigration as it left room for 'cheap labour' and an increasing recruitment of Japanese from both Hawaii and Japan as they sought industrialists to replacement Chinese labourers. [20]. 'Between 1901 and 1908, a time of unrestricted immigration, 127,000 Japanese entered the U.S.'[21] However, as the number of Japanese in the United States increased, resentment against their success in the farming industry and fears of a "yellow peril" grew into an anti-Japanese movement similar to that faced by earlier Chinese immigrants.[22] Increased pressure from the Asiatic Exclusion League and the San Francisco Board of Education, forced President Roosevelt to negotiate the Gentlemen's Agreement with Japan in 1907. It was agreed that Japan would stop issuing valid passports for the U.S. However, Japanese women were allowed to immigrate if they were the wives of U.S. residents. This agreement curtailed Japanese immigration to the U.S. Japanese immigration to the U.S. effectively ended when Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924 which banned all but a token few Japanese people. The ban on immigration produced unusually well-defined generational groups within the Japanese American community. Initially, there was an immigrant generation, the Issei, and their U.S.-born children, the Nisei Japanese American. The Issei were exclusively those who had immigrated before 1924. Because no new immigrants were permitted, all Japanese Americans born after 1924 were — by definition — born in the U.S. This generation, the Nisei, became a distinct cohort from the Issei generation in terms of age, citizenship, and English language ability, in addition to the usual generational differences. Institutional and interpersonal racism led many of the Nisei to marry other Nisei, resulting in a third distinct generation of Japanese Americans, the Sansei.[23] [24][25]It was only in 1952 that the Senate and House voted the McCarran-Walter Act which allowed Japanese immigrants to become naturalized U.S. citizens. But significant Japanese immigration did not occur until the Immigration Act of 1965 which ended 40 years of bans against immigration from Japan and other countries.

Anti-Japanese sentiment

Discriminatory Anti-Oriental attitudes have historically been part of popular sentiment in the United States especially on the West coast. Resentment was based on racial feelings and as well as resentment of immigrants' willingness to labour for low pay and economic competition as a result of Japanese success in labouring industries such as Agriculture. Anti-Japanese feelings were largely concentrated in California. Between 1901 and 1920 it was an extremely heterogenous state. The state's population compromised of culturally insulated and isolated immigrant communities and as a result Californian society was unintegrated, unstable and loosely organised. Lack of integration led to more distinguished cultural, linguistic differences between minority Oriental Japanese and white European groups. As a result, public hostility was based on the fear of 'yellow peril' and 'antagonist misunderstandings' of Japanese cultural differences to the model American in American society.[26] Sources show that anti-Japanese sentiment publically came known in 1900 with local labour groups calling a major anti-Japanese protest in San Francisco on May 7th 1900. This anti-Japanese racism become increasingly xenophobic after the Japanese victory over the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War (1905–6). The Asiatic Exclusion League (1905) and the Californian Board of Education passed a regulation whereby children of Japanese descent would be required to attend racially segregated schools.

Influential figures such as the Mayor of San Francisco, James Phelan, aligned themselves with this popular discontent claiming:

‘The Japanese are not bona fide citizens. They are not the stuff of which American citizens can be made…we have nothing against Japanese but as they will not assimilate with us and their social life is so different from ours, let them keep at a respectful distance.’ [27]

Also, anti-Japanese was felt in various industries, Japanese success and dominance in Agriculture in the late nineteeth and early twentieth century was deemed a threat to personal stability and family life and so there was an increased pressure by the general public calling for discriminating law enforcement such as the Californian Alien Law of 1913 prohibiting Japanese immigrants from owning land. (see section on Agriculture).

Federal immigration and Naturalization laws during the twentieth century demonstrated the public hostility to Asians and later internment of Japanese Americans in relocation camps in 1942 due to a national sentiment of 'disloyalty' cemented feelings of Anti-Japanese sentiment (see section on Internment)

Farming[edit]

Japanese-Americans have made significant contributions to agricultural development in Western-Pacific parts of the United States, especially in California and Hawaii. Similar to European American settlers, the Issei, the majority of whom were young adult males, immigrated to America searching for better economic conditions and the majority settled in Western pacific states settling for manual labour jobs in various industries such as ‘railroad, cannery and logging camp labourers.[28] [29] The Japanese workforce were diligent and extremely hardworking, inspired to earn enough money to return and retire in Japan.[30] Consequently, this collective ambition enabled the Issei to work in agriculture as tenant farmers fairly promptly and by ‘1909 approximately 30,000 Japanese labourers worked in the Californian agriculture’.[31]This transition occurred relatively smoothly due to a strong inclination to work in agriculture which had always been an occupation that had been looked upon with respect in Japan. Progress was made by the Issei in agriculture despite struggles faced cultivating the land, including harsh environment problems such as harsh weather and persistent issues with grass-hoppers. Economic difficulties and discriminating socio-political pressures such as the anti-alien laws (see California Alien Land Law of 1913) were further obstacles. Neveretheless, second-generation Nisei were not impacted by these laws as a result of being legal American citizens, therefore their important roles in West Coast agriculture persisted [32] Japanese immigrants brought a sophisticated knowledge of cultivation including knowledge of soils, fertilizers, skills in land reclamation, irrigation and drainage. This knowledge combined with Japanese traditional culture respecting the soil and hard-work, led successful cultivation of crops on previously marginal lands.[33] [34] According to sources, by 1941 Japanese Americans ‘were producing between thirty and thirty-five per cent by value of all commercial truck crops grown in California as well as occupying a dominant position in the distribution system of fruits and vegetables.’[35]

The role of Issei in agriculture prospered in the early twentieth century. It was only in the event of the Internment of Japanese Americans in 1942 that many lost their agricultural businesses and farms. Although this was the case, Japanese Americans remain involved in these industries today, particularly in southern California and to some extent, Arizona by the areas' year-round agricultural economy, and descendants of Japanese pickers who adapted farming in Oregon and Washington state.[36] Agriculture also played a key role during the internment of Japanese Americans. World War II internment camps, were located in desolate spots such as Poston, in the Arizona desert, and Tule Lake, California, at a dry mountain lake bed. Agricultural programs were put in place at relocation centres with the aim of growing food for direct consumption by inmates. There was also a less important aim of cultivating 'war crops' for the war effort. Agriculture in internment camps was faced with multiple challenges such as harsh weather and climate conditions however, on the most part the agricultural programs were a success mainly due to inmate knowledge and interest in agriculture. [37] [38] Due to their tenacious efforts, these farm lands remain active today.[39]

Internment[edit]

During World War II, an estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals or citizens residing in the United States were forcibly interned in ten different camps across the US, mostly in the west. The Internment was a 'system of legalized racial oppression' and were based on the race or ancestry rather than activities of the interned. Families, including children, were interned together. Each member of the family was allowed to bring two suitcases of their belongings. Each family, regardless of its size, was given one room to live in. The camps were fenced in and patrolled by armed guards. For the most part, the internees remained in the camps until the end of the war, when they left the camps to rebuild their lives.[40][41]

World War II service[edit]

Many Japanese Americans served with great distinction during World War II in the American forces.

Nebraska Nisei Ben Kuroki became a famous Japanese-American soldier of the war after he completed 30 missions as a gunner on B-24 Liberators with the 93rd Bombardment Group in Europe. When he returned to the US he was interviewed on radio and made numerous public appearances, including one at San Francisco's Commonwealth Club where he was given a ten-minute standing ovation after his speech. Kuroki's acceptance by the California businessmen was the turning point in attitudes toward Japanese on the West Coast. Kuroki volunteered to fly on a B-29 crew against his parent's homeland and was the only Nisei to fly missions over Japan. He was awarded a belated Distinguished Service Medal by President George W. Bush in August 2005.

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team/100th Infantry Battalion is one of the most highly decorated unit in U.S. military history. Composed of Japanese Americans, the 442nd/100th fought valiantly in the European Theater. The 522nd Nisei Field Artillery Battalion was one of the first units to liberate the prisoners of the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau. Hawaiʻi Senator Daniel Inouye was a veteran of the 442nd. Additionally the Military Intelligence Service consisted of Japanese Americans who served in the Pacific Front.

On October 5, 2010, the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Infantry Battalion, as well as the 6,000 Japanese Americans who served in the Military Intelligence Service during the war.[42]

Post-World War II and redress[edit]

In the U.S., the right to redress is defined as a constitutional right, as it is decreed in the First Amendment to the Constitution.

Redress may be defined as follows:

- 1. the setting right of what is wrong: redress of abuses.

- 2. relief from wrong or injury.

- 3. compensation or satisfaction from a wrong or injury

Reparation is defined as:

- 1. the making of amends for wrong or injury done: reparation for an injustice.

- 2. compensation in money, material, labor, etc., payable by a defeated country to another country or to an individual for loss suffered during or as a result of war.

- 3. restoration to good condition.

- 4. repair. (“Legacies of Incarceration,” 2002)

The campaign for redress against internment was launched by Japanese Americans in 1978. The Japanese American Citizens’ League (JACL) asked for three measures to be taken as redress: $25,000 to be awarded to each person who was detained, an apology from Congress acknowledging publicly that the U.S. government had been wrong, and the release of funds to set up an educational foundation for the children of Japanese American families. Eventually, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 granted reparations to surviving Japanese-Americans who had been interned by the United States government during World War II and officially acknowledged the "fundamental violations of the basic civil liberties and constitutional rights" of the internment.[43]

Under the 2001 budget of the United States, it was decreed that the ten sites on which the detainee camps were set up are to be preserved as historical landmarks: “places like Manzanar, Tule Lake, Heart Mountain, Topaz, Amache, Jerome, and Rohwer will forever stand as reminders that this nation failed in its most sacred duty to protect its citizens against prejudice, greed, and political expediency” (Tateishi and Yoshino 2000).

No comments:

Post a Comment