Cell Nucleolus

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The nucleolus (/njuːˈkliːələs/ or /ˌnjuːkliˈoʊləs/, plural nucleoli /njuːˈkliːəˌlaɪ/ or /ˌnjuːkliˈoʊlaɪ/) is the largest structure in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells.[1] It is best known as the site of ribosome biogenesis. Nucleoli also participate in the formation of signal recognition particles and play a role in the cell's response to stress.[2] Nucleoli are made of proteins, DNA and RNA and form around specific chromosomal regions called nucleolar organizing regions. Malfunction of nucleoli can be the cause of several human conditions called "nucleolopathies"[3] and the nucleolus is being investigated as a target for cancer chemotherapy.[4][5]

Contents

[hide]History[edit]

The nucleolus was identified by bright-field microscopy during the 1830s.[6] Little was known about the function of the nucleolus until 1964, when a study[7] of nucleoli by John Gurdon and Donald Brown in the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis generated increasing interest in the function and detailed structure of the nucleolus. They found that 25% of the frog eggs had no nucleolus and that such eggs were not capable of life. Half of the eggs had one nucleolus and 25% had two. They concluded that the nucleolus had a function necessary for life. In 1966 Max L. Birnstiel and collaborators showed via nucleic acid hybridization experiments that DNA within nucleoli code for ribosomal RNA.[8][9]

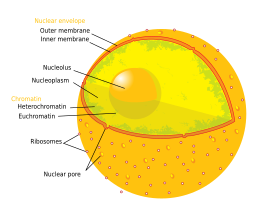

Structure[edit]

Three major components of the nucleolus are recognized: the fibrillar center (FC), the dense fibrillar component (DFC), and the granular component (GC).[1] Transcription of the rDNA occurs in the FC.[10] The DFC contains the protein fibrillarin,[10] which is important in rRNA processing. The GC contains the protein nucleophosmin,[10] (B23 in the external image) which is also involved in ribosome biogenesis.

However, it has been proposed that this particular organization is only observed in higher eukaryotes and that it evolved from a bipartite organization with the transition from anamniotes to amniotes. Reflecting the substantial increase in the DNA intergenic region, an original fibrillar component would have separated into the FC and the DFC.[11]

Another structure identified within many nucleoli (particularly in plants) is a clear area in the center of the structure referred to as a nucleolar vacuole.[12] Nucleoli of various plant species have been shown to have very high concentrations of iron[13] in contrast to human and animal cell nucleoli.

The nucleolus ultrastructure can be seen through an electron microscope, while the organization and dynamics can be studied through fluorescent protein tagging and fluorescent recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). Antibodies against the PAF49 protein can also be used as a marker for the nucleolus in immunofluorescence experiments.[14]

Function and ribosome assembly[edit]

In ribosome biogenesis, two of the three eukaryotic RNA polymerases (pol I and III) are required, and these function in a coordinated manner. In an initial stage, the rRNA genes are transcribed as a single unit within the nucleolus by RNA polymerase I. In order for this transcription to occur, several pol I-associated factors and DNA-specific trans-acting factors are required. In yeast, the most important are: UAF (upstream activating factor), TBP (TATA-box binding protein), and CF (core factor), which bind promoter elements and form the preinitiation complex (PIC), which is in turn recognized by RNA pol. In humans, a similar PIC is assembled with SL1, the promoter selectivity factor (composed of TBP and TBP-associated factors, or TAFs), transcription initiation factors, and UBF (upstream binding factor). RNA polymerase I transcribes most rRNA transcripts 28S, 18S, and 5.8S) but the 5S rRNA subunit (component of the 60S ribosomal subunit) is transcribed by RNA polymerase III.[15]

Transcription of rRNA yields a long precursor molecule (45S pre-rRNA) which still contains the ITS and ETS. Further processing is needed to generate the 18S RNA, 5.8S and 28S RNA molecules. In eukaryotes, the RNA-modifying enzymes are brought to their respective recognition sites by interaction with guide RNAs, which bind these specific sequences. These guide RNAs belong to the class of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) which are complexed with proteins and exist as small-nucleolar-ribonucleoproteins (snoRNPs). Once the rRNA subunits are processed, they are ready to be assembled into larger ribosomal subunits. However, an additional rRNA molecule, the 5S rRNA, is also necessary. In yeast, the 5S rDNA sequence is localized in the intergenic spacer and is transcribed in the nucleolus by RNA pol.

In higher eukaryotes and plants, the situation is more complex, for the 5S DNA sequence lies outside the Nucleolus Organiser Region (NOR) and is transcribed by RNA pol III in the nucleoplasm, after which it finds its way into the nucleolus to participate in the ribosome assembly. This assembly not only involves the rRNA, but ribosomal proteins as well. The genes encoding these r-proteins are transcribed by pol II in the nucleoplasm by a "conventional" pathway of protein synthesis (transcription, pre-mRNA processing, nuclear export of mature mRNA and translation on cytoplasmic ribosomes). The mature r-proteins are then "imported" back into the nucleus and finally the nucleolus. Association and maturation of rRNA and r-proteins result in the formation of the 40S (small) and 60S (large) subunits of the complete ribosome. These are exported through the nuclear pore complexes to the cytoplasm, where they remain free or become associated with the endoplasmic reticulum, forming rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER).[16][17]

In human endometrial cells, a network of nucleolar channels is sometimes formed. The origin and function of this network has not yet been clearly identified.[18]

Sequestration of proteins[edit]

In addition to its role in ribosomal biogenesis, the nucleolus is known to capture and immobilize proteins, a process known as nucleolar detention. Proteins that are detained in the nucleolus are unable to diffuse and to interact with their binding partners. Targets of this post-translational regulatory mechanism include VHL, PML, MDM2, POLD1, RelA, HAND1 and hTERT, among many others. It is now known that long noncoding RNAs originating from intergenic regions of the nucleolus are responsible for this phenomenon.[19]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b O'Sullivan JM, Pai DA, Cridge AG, Engelke DR, Ganley AR (2013). "The nucleolus: a raft adrift in the nuclear sea or the keystone in nuclear structure?". Biomolecular Concepts. 4 (3): 277–86. doi:10.1515/bmc-2012-0043. PMC 5100006

. PMID 25436580.

. PMID 25436580. - ^ Olsen, Mark OJ (December 2010). "Nucleolus: Structure and Function". ELS. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0005975.pub2. ISBN 0-470-01617-5. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Hetman M (2014). "Role of the nucleolus in human diseases. Preface". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1842 (6): 757. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.03.004. PMID 24631655.

- ^ Quin JE, Devlin JR, Cameron D, Hannan KM, Pearson RB, Hannan RD (2014). "Targeting the nucleolus for cancer intervention". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1842 (6): 802–16. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.009. PMID 24389329.

- ^ Woods SJ, Hannan KM, Pearson RB, Hannan RD (2015). "The nucleolus as a fundamental regulator of the p53 response and a new target for cancer therapy". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1849 (7): 821–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.10.007. PMID 25464032.

- ^ Pederson T (2011). "The nucleolus". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 3 (3). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000638. PMC 3039934

. PMID 21106648.

. PMID 21106648. - ^ BROWN DD, GURDON JB (1964). "ABSENCE OF RIBOSOMAL RNA SYNTHESIS IN THE ANUCLEOLATE MUTANT OF XENOPUS LAEVIS" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 51: 139–46. doi:10.1073/pnas.51.1.139. PMC 300879

. PMID 14106673.

. PMID 14106673. - ^ Birnstiel ML, Wallace H, Sirlin JL, Fischberg M (1966). "Localization of the ribosomal DNA complements in the nucleolar organizer region of Xenopus laevis". National Cancer Institute Monograph. 23: 431–47. PMID 5963987.

- ^ Wallace H, Birnstiel ML (1966). "Ribosomal cistrons and the nucleolar organizer". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 114 (2): 296–310. doi:10.1016/0005-2787(66)90311-x. PMID 5943882.

- ^ a b c Sirri V, Urcuqui-Inchima S, Roussel P, Hernandez-Verdun D (2008). "Nucleolus: the fascinating nuclear body". Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 129 (1): 13–31. doi:10.1007/s00418-007-0359-6. PMC 2137947

. PMID 18046571.

. PMID 18046571. - ^ Thiry M, Lafontaine DL (2005). "Birth of a nucleolus: the evolution of nucleolar compartments". Trends Cell Biol. 15 (4): 194–9. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.02.007. PMID 15817375. as PDF

- ^ Beven AF, Lee R, Razaz M, Leader DJ, Brown JW, Shaw PJ (1 June 1996). "The organization of ribosomal RNA processing correlates with the distribution of nucleolar snRNAs". J. Cell Sci. 109 (6): 1241–51. PMID 8799814.

- ^ Roschzttardtz H, Grillet L, Isaure MP, et al. (2011). "Plant cell nucleolus as a hot spot for iron". J. Biol. Chem. 286 (32): 27863–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.C111.269720. PMC 3151030

. PMID 21719700.

. PMID 21719700. - ^ PAF49 antibody | GeneTex Inc. Genetex.com. Retrieved on 2013-03-03.

- ^ Champe, Pamela C.; Harvey, Richard A.; Ferrier, Denise R. (2005). Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews: Biochemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-2265-0.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. pp. 331–3. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

- ^ Cooper, Geoffrey M.; Hausman, Robert E. (2007). The Cell: A Molecular Approach (4th ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 371–9. ISBN 0-87893-220-8.

- ^ Wang T, Schneider J; Origin and fate of the nucleolar channel system of normal human endometrium; Cell Res. (1992); 2(2), 97-102

- ^ Audas TE, Jacob MD, Lee S (2012). "Immobilization of proteins in the nucleolus by ribosomal intergenic spacer noncoding RNA". Mol Cell. 45 (2): 147–57. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.012. PMID 22284675.

No comments:

Post a Comment