Nobel prize in physics awarded for work on cosmology – as it happened

James Peebles, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz honoured for ‘improving our understanding of evolution of universe and Earth’s place in the cosmos’

Updated

That's a wrap

And there we leave the physics prize for another year. Huge congratulations go to James Peebles, who set the foundations for modern cosmology with his work on the big bang, dark matter and dark energy, and to Didier Queloz and Michel Mayor who spotted the first world beyond the solar system.

Here is my colleague Hannah Devlin’s news story on the prize:

We’ll be back again tomorrow for the Nobel prize in chemistry. Is it time for gene editing to win the gong? Join us from 10.15am!

There are two methods that astronomers use to spot planets around other stars. One is the so-called transit method where scientists watch for planets as they wander across the face of their parent star. Even though the star is but a pinprick in the heavens, sensitive telescopes can often detect the minuscule dimming of the starlight as the planet goes by and casts its shadow on the detector. It’s been extremely successful - Nasa’s Kepler’s mission is one space telescope that has exploited transits to find hoards of new planets.

Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz used a different technique. They looked at how stars are pulled around by planets that swing around them. This radial velocity method exploits the Doppler effect. In this case, as a planet’s gravity pulls its star towards Earth - with its telescope-wielding astronomers - light from the star is shifted towards the blue wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. The rays are basically squeezed up, making them bluer. As the planet goes around the star and pulls it backwards, the starlight is stretched out and so turns more towards the red end of the electromagnetic spectrum. Measure these wavelength variations and you can work out first if there’s an unseen planet in orbit around a star, and secondly how long a year lasts on the world.

Updated

Advertisement

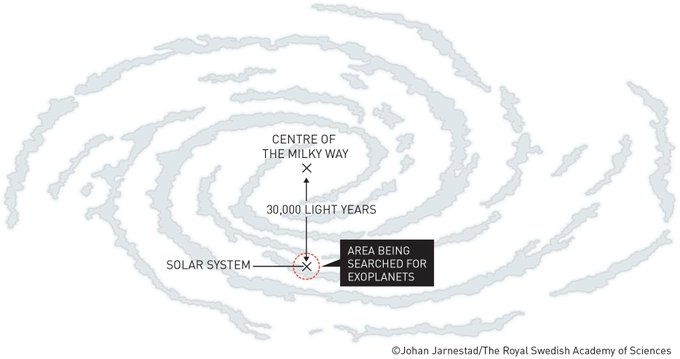

How much of the galaxy have we searched for planets beyond the solar system? Not an awful lot...so we can only imagine what lies out there.

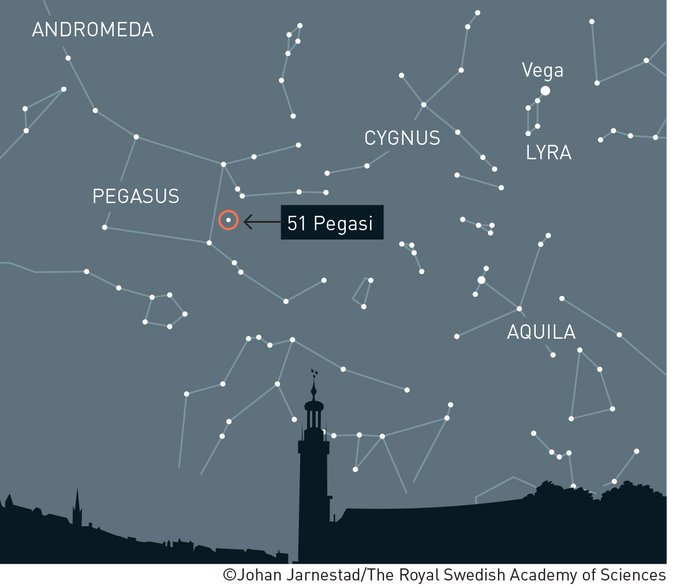

This year’s Physics Laureates Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz have explored our home galaxy, the Milky Way, looking for unknown worlds. In 1995, they made the first discovery of a planet outside our solar system, an exoplanet, orbiting a solar-type star, 51 Pegasi.#NobelPrize

The discovery by 2019 #NobelPrize laureates Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz started a revolution in astronomy and over 4,000 exoplanets have since been found in the Milky Way. Strange new worlds are still being discovered, with an incredible wealth of sizes, forms and orbits.

756 people are talking about this

Unlike many news organisations, we chose an approach that means all our reporting is free and available for everyone. We need your support to keep delivering quality journalism, to maintain our openness and to protect our precious independence. Every reader contribution, big or small, is so valuable.

For as little as $1 you can support us – and it only takes a minute. Thank you. Make a contribution - The Guardian

Here’s Didier Queloz talking about the discovery of that first known exoplanet.

“At that time I didn’t think at all it was a planet. I just thought something was wrong.”

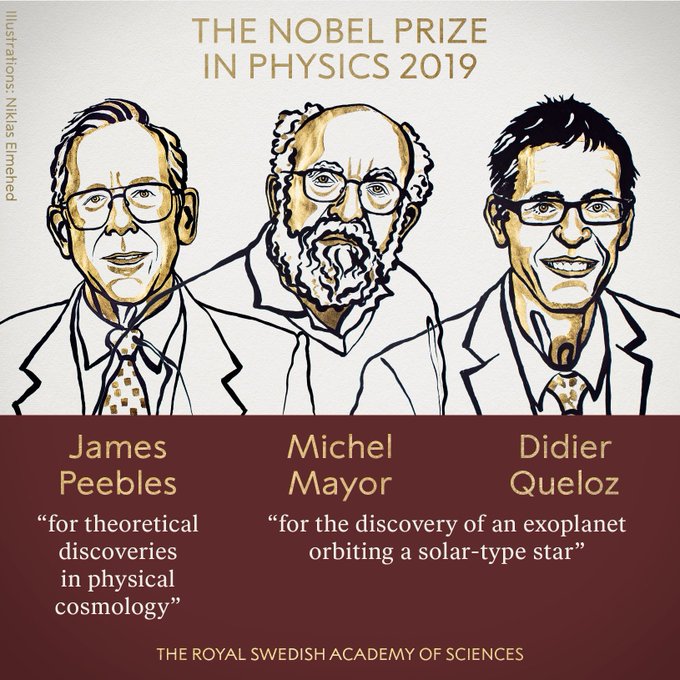

Here are the official citations for this year’s winners:

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Physics 2019 “for contributions to our understanding of the evolution of the universe and Earth’s place in the cosmos”

With one half to James Peebles at Princeton University “for theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology” and the other half jointly to Michel Mayor at the University of Geneva and Didier Queloz at the University of Geneva, Switzerland and the University of Cambridge, UK.

But what about Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz?

In October 1995 the duo announced the first discovery of a planet outside our solar system. Using custom-made instruments, they spotted the Jupiter-like planet 51 Pegasi b from the Haute-Provence Observatory in southern France.

The work led to a surge of similar such discoveries. Today, more than 4,000 exoplanets have been spotted in the Milky Way, and the discoveries keep on coming. These are wild and wonderful worlds. The easiest to spot are vast, blisteringly-hot gas giants that swing around their parent stars on extremely close-in orbits. Others appear to be rocky and lurk in the habitable zone, where liquid water would run freely. Still others are thought to be exotic water worlds: their entire surface an ocean.

As more planets are found, and more observatories are launched in to orbit, or switched on here on Earth, astronomers are getting closer to answering what is perhaps one of the most profound questions humans ask: are we alone?

Advertisement

Here’s James Peebles in 2017 talking about the history of modern cosmology at the Perimeter Institute in Canada.

James Peebles’ work shone a light on the universe’s structure and history and laid the foundations for cosmology for the past 50 years. The big bang model describes how the universe evolved over nearly 14bn years from a hot, dense ball to the vast, cold and expanding universe of today.

Barely 400,000 years after the big bang, the murky universe cleared and became transparent allowing light rays to travel through space. Today that relic radiation remains as the cosmic microwave back ground. In it are written many of the early universe’s secrets.

With theoretical tools and calculations, James Peebles interpreted these traces from the infancy of the universe and discovered new physical processes. He found that only 5% of the observable universe is known to us in the form of stars, planets and people. The remaining 95% is mysterious and made up of what physicists call dark energy and dark matter. So-called dark energy is said to drive the expansion of the universe, while dark matter is the invisible substance that appears to hang around galaxies, revealing itself only by its gravitational draw.

Peebles has been asked if he has advice for young people considering a career in science. He does indeed:

You should enter it for the love of the science. The awards and prizes, they are charming and very much appreciated, but that’s not part of your plans. You should enter science because you’re fascinated by it.

“We still must admit that the dark matter and dark energy are mysterious,” says John Peebles in an interview with the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. “There are still many open questions … what in the world is this dark matter?”

Is there life on other planets, he’s asked?

He’s pretty sure there will be something we’ll call life on other planets. But adds:

“Whether it will be like life on Earth is very difficult for me to know, maybe chemists will sort that out … we can be very sure we will never ever see these other lives, these other planets.”

Updated

A theoretical framework, developed by James Peebles over two decades, has become the foundation of our modern understanding of the universe’s history, from the big bang to the present day.

Meanwhile, in 1995, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz discovered the first planet outside our solar system, an exoplanet, orbiting a sun-type star, 51 Pegasi.

Advertisement

Well the prize was certainly coming and it’s well deserved. Astronomers have found thousands of exoplanets since this trio effectively launched the field. The discover of worlds beyond our solar system has truly transformed our understanding not only of the Milky Way, but of our place within it.

Updated

And the winners are

BREAKING NEWS:

The 2019 #NobelPrize in Physics has been awarded with one half to James Peebles “for theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology” and the other half jointly to Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz “for the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting a solar-type star.”

9,881 people are talking about this

No comments:

Post a Comment