Summary of Berberine

Primary Information, Benefits, Effects, and Important Facts

Berberine is an alkaloid extracted from various plants used in traditional Chinese medicine.

Berberine is supplemented for its anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic effects. It can also improve intestinal health and lower cholesterol. Berberine is able to reduce glucose production in the liver. Human and animal research demonstrates that 1500mg of berberine, taken in three doses of 500mg each, is equally effective as taking 1500mg of metformin or 4mg glibenclamide, two pharmaceuticals for treating type II diabetes. Effectiveness was measured by how well the drugs reduced biomarkers of type II diabetes.

Berberine may also synergize with anti-depressant medication and help with body fat loss. Both of these benefits need additional evidence behind them before berberine can be recommended specifically for these reasons.

Berberine’s main mechanism is partly responsible for its anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory effects. Berberine is able to activate an enzyme called Adenosine Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) while inhibiting Protein-Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B (PTP1B).

Berberine has a high potential to interact with a medications, and some interactions may be serious.

Berberine is one of the few supplements in the Examine.com database with human evidence that establishes it to be as effective as pharmaceuticals.

Things to Know

Do Not Confuse With

Piperine (Black Pepper extract), Berberol (Brand name), Berberrubine (Metabolite)

Things to Note

- High doses of berberine taken acutely, due to their poor intestinal uptake rate, may cause cramping and diarrhea; for this reason, berberine should be taken in multiple doses throughout the day

- Berberine is known to inhibit CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4, which can lead to a host of drug interactions, some of which can be serious

- Berberine is known to induce the protein concent of P-glycoprotein

- Berberine interacts with organic anion transporter proteins, which may limit tissue uptake of metformin

- Berberine may interact with microlide antibiotics such as azithromycin and clarithromycin at hERG channels on the heart, leading to serious cardiotoxicity

Is used for

Also used for

Is a form of

Goes Well With

- P-glycoprotein (P-Gp) inhibitors increase absorption rate, with Milk Thistle demonstrated in humans and Stephania tetrandra being promising

- Sodium caprate (increases absorption, not related to P-Glycoprotein)

- Atrogin-1 inhibition (theoreticallyreverses the possible degradation of lean mass associated with AMPK activation into synthesis)

Does Not Go Well With

- Phosphodiesterase inhibitors (can attenuate but not abolish the increase in cAMP that PDE inhibitors result in, and may reduce their fat-burning effects)

Caution Notice

Known to interact with enzymes of Drug Metabolism. Also may interact with microlide antibiotics such as azithromycin and clarithromycin at hERG channels on the heart, leading to serious cardiotoxicity.

How to Take

Recommended dosage, active amounts, other details

The standard dose of berberine is 900-2,000mg a day, divided into three to four doses.

Berberine should be taken with a meal, or shortly after, to take advantage of the blood glucose and lipid spike associated with eating.

Too much berberine at once can result in stomach upset, cramping, and diarrhea.

Editors' Thoughts on Berberine

Yeah, so I guess I'll just use this area to talk about the 'bad' associated with this supplement. Consider it a panacea or at least inert except for the following (hey, nothing is perfect):

Kurtis Frank

Frequently Asked Questions

Questions and answers regarding Berberine

Q: 5 supplements (and foods) for a stronger heart

A: Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the #1 cause of death globally. But a mix of the right foods and complementary supplements can help decrease your risk factors.

Read full answer to "5 supplements (and foods) for a stronger heart"

A: Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the #1 cause of death globally. But a mix of the right foods and complementary supplements can help decrease your risk factors.

Read full answer to "5 supplements (and foods) for a stronger heart"

Human Effect Matrix

The Human Effect Matrix looks at human studies (it excludes animal and in vitro studies) to tell you what effects berberine has on your body, and how strong these effects are.

Scientific Research

Table of Contents:

- 1 Sources and Structure

- 1.1 Sources

- 1.2 Structure

- 1.3 Berberine Complexes

- 1.4 Related Structures

- 2 Pharmacology

- 2.1 Absorption

- 2.2 Distribution

- 2.3 Metabolism

- 2.4 Excretion

- 2.5 Enzymatic Interactions

- 3 Molecular Targets

- 3.1 AMPK

- 4 Longevity and Life Extension

- 4.1 Telomeres

- 5 Neurology

- 5.1 Pharmacokinetics

- 5.2 Adrenergic Neurotransmission

- 5.3 Serotoninergic Neurotransmission

- 5.4 Dopaminergic Neurotransmission

- 5.5 Memory and Learning

- 5.6 Depression

- 5.7 Sedation

- 5.8 Analgesia

- 5.9 Alzheimer's Disease

- 5.10 Neuroprotection

- 5.11 Addiction and Dependence

- 6 Cardiovascular Health

- 6.1 Cardiac Tissue

- 6.2 Triglycerides

- 6.3 Blood Flow

- 6.4 Platelets

- 6.5 Atherosclerosis

- 7 Fat Mass and Obesity

- 8 Interactions with Glucose Metabolism

- 8.1 Absorption

- 8.2 Interventions

- 9 Skeletal Muscle and Physical Performance

- 10 Skeleton and Bone Metabolism

- 10.1 Calcitriol

- 10.2 Joint Inflammation

- 11 Inflammation and Immunology

- 11.1 Inflammation (General)

- 11.2 Macrophages

- 11.3 T-Cells

- 11.4 Virology

- 12 Interactions with Oxidation

- 12.1 Endoplasmic Reticulum

- 12.2 Lipid Peroxidation

- 13 Interactions with Hormones

- 13.1 Testosterone

- 13.2 Estrogen

- 13.3 Leptin

- 13.4 GLP-1

- 14 Cancer Metabolism

- 14.1 Mechanisms (General)

- 14.2 Proliferation and Angiogenesis

- 14.3 Migration and Metastasis

- 14.4 Autophagy

- 14.5 Adjunct Therapy Potential

- 14.6 Brain

- 14.7 Breast

- 14.8 Liver

- 14.9 Oral

- 14.10 Thyroid

- 14.11 Colon

- 14.12 Prostate

- 14.13 Immunological Cancers

- 15 Interactions with the Liver (Hepatology)

- 15.1 Glucose Interactions

- 15.2 Lipids and Cholesterol

- 15.3 Fibrosis

- 15.4 Liver Enzymes

- 15.5 Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- 16 Interactions with the Intestinal Tract

- 16.1 Interactions with Glucose Metabolism

- 16.2 Diarrhea

- 16.3 Ulcerative Colitis

- 16.4 Colonic Microflora

- 17 Interactions with other Organ Systems

- 18 Other Possible Therapeutic Roles

- 19 Nutrient-Nutrient Interactions

- 19.1 Metformin

- 19.2 Statins

- 19.3 Policosanol and Red Yeast Extract

- 19.4 Sodium Caprate

- 19.5 Berberol

- 19.6 Er-Xian

- 20 Safety and Toxicology

- 20.1 General

- 20.2 Contraindictions

1Sources and Structure

1.1. Sources

Berberine (2,3-methylenedioxy-9,10-dimethoxy-protoberberine) has been used historically in Ayurvedaand Traditional Chinese medicine (vicariously through herbs which contain it) as an anti-microbial, anti-protozoal, and anti-diarrheal agent.[4]

It has shown efficacy against various bacteria strains such as cholera, giardia, shigella, and salmonella; potentially also staphylococcus, streptococcus, and clostridium.[4][5] Its actions against protozoa extend to Giardia lamblia, Trichomonas vaginalis, Leishmania donovani, and Malaria.[6][7][8]Surprisingly, crude extracts are more potent than isolated berberine in these anti-protozoan effects suggesting synergistic or additive effects with other compounds in these plants.[9]

Various effects against bacteria and protozoa, which underlies a fair bit of traditional usage of the plants containing Berberine

Berberine has been isolated from various plant families including Papaveraceae, Berberidaceae, Fumariaceae, Menispermaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rutaceae, and Annonaceae[10]

- (Berberidaceae family) Berberis Aristata (Tree Turmeric or Indian Barberry)[4] at 5% of the roots or 4.2% of stem and bark.[11] The Berberis genera that also includes Berberine include vulgaris (1.24%), petiolaris (0.43%) as well as thunbergii, aquifolium, and asiatica.[4] Other plant sources of Berberine in this family include Caulis mahoniae[11] and Mahonia aquifolium (Oregon Grape)

- (Rutaceae family) Phellodendron Amurense (Amur Cork Tree, Huang Bai)[4]

Appears to be a common alkaloid present in a variety of plant families, and most of these plants have traditionally been used for digestion or glucose/diabetes related issues in traditional medicine

1.2. Structure

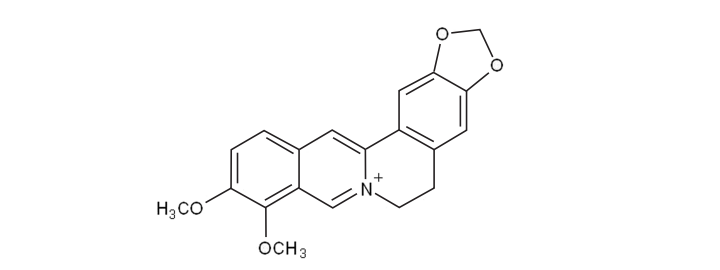

Berberine is known as an isoquinoline alkaloid with the prolonged name of 2,3-methylenedioxy-9,10-dimethoxy-protoberberine.[14] It has a molecular weight of 336.36122g/mol, and is bright yellow in color when isolated.[15]

1.3. Berberine Complexes

Berberine can complex at a 1:1 ratio with the flavonoid baicalin (and to a degree, wogonoside),[16] the complex of which can be formed when Radix Scutellariae and Rhizoma Coptidis (sources of Baicalin and Berberine, respectively) are mixed which occurs in a few Traditional Chinese Medicinecombination therapies. It is thought that these complexes (and another Berberine–glycyrrhizin complex) enhance absorption through forming ion-pairs and enhancing fat solubility, where the glucuronide of Baicalin has its carboxylate ion bind to the quaternary ammonium ion of Berberine.[16]

Berberine, due to its quaternary ammonium ion, can form complexes with other compounds also present in Chinese herbal decoctions; these may have different properties or absorption than Berberine per se

1.4. Related Structures

A related protoberberine compound, Dihydroberberine, appears to have similar effects to Berberine but with lower doses (thus, higher potency), with one study suggesting 560mg/kg Berberine had similar effects to 100mg/kg Dihydroberberine in a high-fat fed rat model measuring adiposity and glucose tolerance.[17] This study noted that dihydroberberine was detected in plasma (with a calculated bioavailability of 2.85%) at a dose that Berberine was not,[17] but noted that Berberine may not have practically relevant improved absorption since it readily converts to Berberine in acidic environments (such as the stomach).[18] The researchers then synthesized 8,8-dimethyldihydroberberine as a pharmaceutical alternative.[18]

Dihydroberberine is also found naturally occurring in some plants (such as Arcangelisia flava[19] and Coptidis Chinensis[20])

Dihydroberberine, although less studied than Berberine itself, appears to be more effective on the main parameter of Berberine inducing AMPK when used in vitro; may merely convert to Berberine in practical situations

The synthetic deriviative known as CPU86017 (p-chlorobenzyltetrahydroberberine chloride or Raisanberine) appears to be a novel cardioprotective drug.[21][22]

2Pharmacology

2.1. Absorption

Overall bioavailability of Berberine is quite low at 'less than 5%'[23][24] with 0.68% having been reported in rats.[25] Studies using 1,000-1,500mg Berberine by itself still appear to exert benefits after absorption, but enhancing absorption theoretically can reduce the dose of Berberine required to reach these effects.

Berberine appears to be subject to P-Glycoprotein mediated efflux from the intestines[26][27] and liver.[28] In the intestines, P-Glycoprotein is responsible for approximately 90% reduced transportation of Berberine[27] and Berberine has been further demonstrated to actually induce (increase) the activity of P-Glycoprotein transporters in the intestine[29][30] which have caused reduced absorption of other compounds subject to P-gp, such as Ciprofloxacin (demonstrated with 25-50mg/kg Berberine in rats; 4-8mg/kg human equivalent).[31]

Using an analogue that doesn't get subject to P-Glycoprotein (IMB-Y53) it is shown that increasing uptake contributes to further anti-diabetic effects[32] and pairing Berberine with compounds that are known to inhibit P-Glycoprotein (Milk Thistle,[33] Ketoconazole,[34] or d-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS)[25]) enhances the biological activity of Berberine.

Berberine has low rates of absorption when taken orally due to both being subject to P-Glycoprotein (ejects Berberine back into the intestines) and increasing the activity of P-Glycoprotein (augmenting its own ejection), but absorption is greatly increased when taken with P-Glycoprotein inhibitors such as Silymarin from Milk Thistle.

Absorption has also been enhanced with Sodium Caprate, a medium chain fatty acid that increases the size of tight junctions between intestinal cells (increasing paracellular permeability reversibly[35]) and appears to not be associated with adverse structural changes to the intestines when used with Berberine in vivo.[36][37] Sodium caprate is associated with improvements in AUC of Berberine by 28% (100mg/kg Berberine with or without 50mg/kg Sodium Caprate[37]) and appears to be further increased with 100mg/kg Sodium Caprate.[38] Enhanced absorption precedes greater post-absorptive effects, such as enhanced AMPK activation over 4 weeks (50mg/kg Sodium Caprate).[36]

Sodium Caprate, an ester of Capric Acid (Decanoic Acid; a constituent of milk fat at 2-3% and Coconut Oil at 10%) appears to enhance absorption via reversibly widening the gaps between intestinal cells and allowing passive diffusion. It is theoretical, but not yet demonstrated, that coingestion of Berberine with food sources of Capric acid could increase absorption of Berberine (and assuming 10% Capric acid content of Coconut oil, it is about 5.5g of Coconut oil for a 150lb human)

Due to low intestinal uptake rate, large doses (1g) are associated with constipation.[39] This constipative effect is also due to some properties of berberine in the colon, and can be useful to reducing watery diarrhea at 400mg, four 100mg doses.[40]

Low absorption may precede intestinal side-effects with high doses, due to large colonic levels

2.2. Distribution

Berberine binds to both Bovine and Human Serum Albumin relatively well and in a 1:1 ratio (indicating a single binding site) and has slightly higher affinity than does the related structure Palmatine;[41] Berberine may also bind to the β-Trp37 residue on Hemoglobin.[42]

2.3. Metabolism

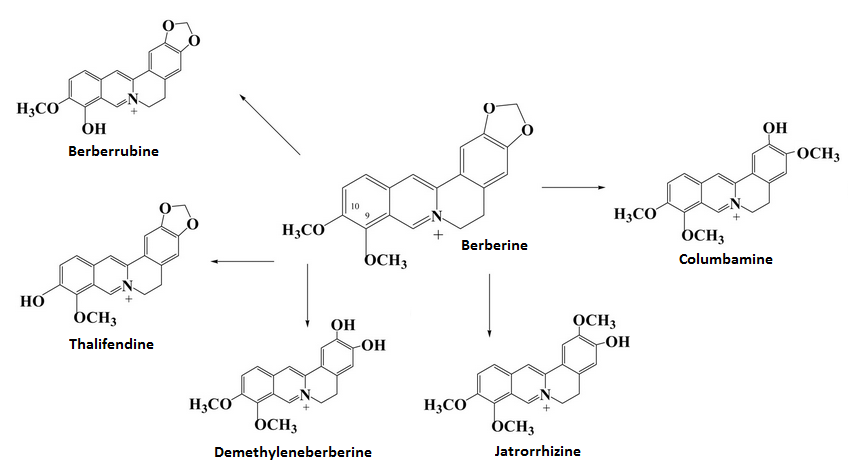

Berberine can have its structure metabolized into four possible metabolites known as Thalifendine, Jatrorrhizine, Berberrubine, and Demethyleneberberine; Berberrubine may passively isomerize between two molecules.[43][44] The metabolism of Berberine into its metabolites involves the enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP1A2 contributing 25.21% and 72.07% of metabolism into Thalifendine (CYP3A4 barely involved at 2.72%) with CYP3A4 as well as the former two being important to metabolism into Demethyleneberberine with a fairly even distrubion.[44]

One experiment with a molecular docking program suggested that CYP2E1, CYP2A6, and CYP2B6 were without any influence on Berberine and CYP2C19, CYP2C9 and CYP3A5 had very weak influence.[44] The lack of involvement of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 were confirmed in HLMs in vitro.[44]

Berberrubine isomers exert the most potent AMPK activation and LDL receptor upregulation among the metabolites, but to a lesser extend than the parent compound Berberine;[44][43] this appears to also apply to the insulin receptor.[44]

Berberine can be possibly metabolized into four different metabolites, with all four metabolites both being active on the same mechanisms as Berberine but to a lesser potency

In rats, all four metabolites have been detected in serum following ingestion of 40mg/kg Berberine[45] and when measuring Berberine concentrations 3 hours after ingestion (rat liver) most Berberine appears to not be metabolized but a small increase in Thalifendine is noted relative to other metabolites.[46]

Berberine appears to be somewhat preserved in the parent form after oral administration

After incubation with intestinal bacteria for 7 days (human and rat), no visible metabolism of Berberine by intestinal bacteria was noted and the tested metabolites were similarly not metabolized further; it is thought that intestinal bacteria does not play a role in the metabolism of Berberine.[45]

2.4. Excretion

Orally ingested Berberine (chloride) at 900mg daily for 3 days was metabolized into three different urinary metabolites, with one (thought to be Jatrorrhizine-3-Sulfate) being the primary metabolite being excreted at 15-125 times more than the other two metabolites (Demethyleneberberine-2-sulfate and Thalifendine-10-sulfate, Berberrubine being undetectable in urine).[47] A later study noted that 900mg (3x300mg) for two days noted that Jatrorrhizine can be detected in the urine as a glucuronide (jatrorrhizine-3-O-β-D-glucuronide) as can Thalifendine (thalifendine-10-O-β-D-glucuronide), Berberrubine (berberrubine-9-O-β-D-glucuronide), and Demethyleneberberine (demethyleneberberine-2,3-di-O-β-D-glucuronide).[46]

One other metabolite has been found, columbamine-2-O-β-D-glucuronide;[46] both Jatrorrhizine and Columbamine can be found naturally occurring in Enantia chlorantha.[48]

Most urinary excretion of Berberine appears to be Jatrorrhizine, with all metabolites having at least once been detected in sulfated or glucuronidated form

2.5. Enzymatic Interactions

In vitro, Berberine appears to inhibit CYP3A4 with an IC50 of 48.9+/-9µM (16.4+/-3.0µg/mL).[49]

For human studies, three divided doses of 300mg Berberine (900mg total) confirmed CYP3A4 inhibitory potential as midazolam AUC was decreased 40%[50] and a few studies on Cyclosporin A (where serum levels increase due to CYP3A4 inhibition) have confirmed CYP3A4 relevance for humans.[51][52] This evidence is all in contrast to a previous rat study suggesting no effect of 100mg/kg bodyweight given an oral Carbamazepine.[29]

Many herbs that Berberine is derived from including Goldenseal[53][54] and Berberis Vulgaris[55] have been shown to inhibit CYP3A4 which is thought to be due to the Berberine content.

The inhibitory effect of Berberine on CYP3A4, an enzyme that metabolizes a fair bit of pharmaceuticals (the same one that St.John's Wort inhibits) appears to be relevant

Berberine has been shown in vitro to inhibit CYP1A2 (IC50 73.2+/-5.5uM; 24.6+/-1.8µg/mL) and CYP2D6 (7.4+/-0.36uM; 2.49+/-0.12µg/mL), suggesting possibly relevant inhibitory potential on CYP2D6.[49] A later study in humans confirmed biolologically relevant CYP2D6 inhibition by 900mg Berberine (in three divided doses of 300mg) and CYP2C9 was also found to be inhibited.[50] This study failed to note any significant inhibition of CYP1A2.[50]

Berberine has been noted to, in vitro, prevent the induction of a variety of CYP mRNAs and when administered to diabetic mice normalize CYP3A11, CYP4A10, and Cyp4A14[56] which are elevated during experimental diabetes.[57] Berberine also suppressed CYP2E1 in vivo.[56]

Various other enzymes appears to be inhibited following oral administration of Berberine to rats or in vitro

3Molecular Targets

3.1. AMPK

Adenosine Mono-phosphate Kinase (AMPK) is a nutrient sensor protein that is central to the actions of various anti-diabetic drugs (Metformin[58]), and appears to be a central lever point for the actions of Berberine. Berberine activates AMPK in a dose and time-dependent manner.[59][60] In investigating how Berberine induces AMPK (commonly associated with energy restriction or some hormetic agents), a possible mechanism is inhibition of complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain[17] which is also observed with the anti-diabetic drugs Metformin and Rosiglitazone (with similar efficacy to the latter, more than the former), resulting in 50% inhibition of respiration at 15umol/L Berberine.[17] Inhibition of this by overexpressing PGC-1α (genetically) can attenuate AMPK activation[61] as can the direct inhibitor Compound C (implicating both the mitochondria and AMPK itself in glucose uptake).[62] Inhibition of Protein Kinase C zeta (PKCζ; upstream of PKB) has also been found to inhibit Berberine-induced glucose uptake, where siRNA for PKCζ that reduced its activity by 50% inhibited 42+/-24% of Berberine-induced glucose uptake.[62]

This increase in AMPK appears to be biologically relevant as it has been found in vivo when rats are injected with 5mg/kg Berberine.[63]

AMPK is induced after Berberine administration, which has been observed in living systems. The regulation appears to be indirect. Mitochondrial uncoupling and a protein known as PKCζ both appear to be involved, but the exact mechanistic pathway it not fully established

AMPK activation by Berberine in HepG2 (liver) cells was found to inhibit both cholesterol and triglyceride synthesis with an IC50 value of 15ug/mL and reduced their respective IC50 values of 10.4 and 5.8 μg/ml.[64] These IC50 values are similar to those seen with LDL-C receptor upregulation and occured at similar time points,[65] suggesting that they are tied in to similar mechanistic roots. Although mediated by AMPK, inhibiting MAPK/ERK appears to attenuate the effects.[64]

Injections of Berberine into the brain also decrease Malonyl-CoA; which is increased when AMPK is inactivated (via ACC activity) and suggests that AMPK activation occurs in neural tissues.[63] This decrease in neural Malonyl-CoA may actually precede mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle.[66][67]

This activation of AMPK extends to adipocytes (fat cells), skeletal myocytes (skeletal muscle cell), and the liver; please refer to their respective sections for more information.

The indirect activation of AMPK appears to extend to a wide variety of tissues in the body

4Longevity and Life Extension

4.1. Telomeres

Binding of an agent to the 3' cap of telomeric DNA can interfere with the telomerase enzyme and give the appearance of a telomerase inhibitor, providing a novel mechanism of action for anti-cancer therapy with interest to life extension.[68] Compounds that tend to associate with this target are large aromatic compounds with a polar charge,[69][70] and Berberine has been found to bind to this target with a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio with relatively high affinity;[71] which has preceded Berberine derivatives being synthesized for higher affinity.[72][73] Binding specificities for Berberine can be read here.[74]

It is thought that telomerase inhibition of Berberine reaches 50% at 35mM concentration,[75] and expression of hTERT has been suppressed at 100ug/mL in SiHa and HeLa cancer cells.[76]

May have telomerase inhibitory potential; of interest mostly to cancer research but with some possible crossover into life extension. Currently no evidence to suggest how this influences lifespan in living models

5Neurology

5.1. Pharmacokinetics

Berberine appears to cross the blood-brain barrier and reach the brain parenchyma in a dose/time-dependent manner.[77]

Berberine can cross the blood brain barrier (BBB)

5.2. Adrenergic Neurotransmission

In regards to the Alpha-Adrenergic receptors (molecular targets of yohimbine), Berberine appears to have relatively more affinity for post-synaptic Alpha-1-Adrenergic receptors than presynaptic A2A receptors.[78] It appears to act as a partial agonist and potential competitive antagonist of these receptors, as assessed by platelets,[79] and appears to extend to its molecular class of Berbanes rather than being a unique property of Berberine.[80] Berberine has been found to interact with a binding site on the Beta-2-Adrenergic receptor.[81]

Appears to interact with adrenergic receptors; practical relevance unknown

Acute administration of Berberine at 5mg/kg injections can raise neural norepinephrine by 31% in mice.[82] Prolonging this treatment for 15 days maintains similar potency (29%), yet increasing the dose to 10mg/kg lessened the increase (12%, not statistically significant).[82] An increase in noradrenaline concent in both the hippocampus and frontal cortex (not striatum) have been noted following oral consumption of 20mg/kg bodyweight in mice, where noradrenaline was increased by 10.8% (hippocampus) and 26.1% (frontal cortex).[83]

Berberine is known to inhibit Monoamine oxidase enzymes with IC50 values of 126uM for MAO-A,[84]and 98.2-98.4uM for MAO-B.[85] These potencies are fairly low and likely not biologically relevant, although a metabolite of Berberine (Jatrorrhizine) has increased potencies on MAO-A and MAO-B with 6uM and 62uM, respectively.[84]

Has been shown to increase noradrenaline in mice brains following both injections and oral treatment, serum levels not yet measured

5.3. Serotoninergic Neurotransmission

Acute administration of Berberine at 5mg/kg injections can raise neural serotonin by 47% in mice, but chronic (15 day) dosing attenuates the increase to 19% but was preserved (53%) with 10mg/kg injections.[82] Oral ingestion of 20mg/kg in mice increased serotonin levels in the hippocampus (22.8%) and frontal cortex (23.6%) but not striatum.[83]

Has been shown to increase serotonin content in some areas of the brains of mice following oral ingestion; serum levels of serotonin following Berberine not yet known

5.4. Dopaminergic Neurotransmission

Berberine has been found to inhibit the tyrosine hydroxylase enzyme in PC12 cells in vitro.[86] This enzyme catalyzes the bioconversion of L-Tyrosine into the dopamine precursor L-DOPA.

Acute administration of Berberine at 5mg/kg injections can raise neural dopamine by 31% in mice, which increased to 53% over 15 days of administration; no further increase was noted at 10mg/kg injections over 15 days though (31%).[82] Ingestion of 20mg/kg Berberine in mice failed to significantly modify dopamine in the striatum, frontal cortex, or hippocampus.[83]

Has been shown to increase dopamine concentration in some areas of the brain following oral administration

5.5. Memory and Learning

Berberine has been noted to preserve Long-term potentiation (LTP) in perforant path-dentate gyrus synapses following 100mg/kg ingestion of Berberine over 11 weeks in rats.[87] LTP tends to be reduced in diabetes.[88][89] No alterations in cell count or apoptosis in the hippocampus were noted in this study,[87] despite apoptosis in the hippocampus being related to Diabetes-induced memory losses[90] and improvements in cognition as assessed by a spatial recognition memory in Y-maze as passive avoidance task were noted (not outperforming non-diabetic control, but outperforming diabetic control and 50mg/kg Berberine which was too low to be significant).[87] A reduced rate of diabetes-induced memory loss has been noted elsewhere with 25-100mgkg Berberine twice daily (total dose 50-200mg/kg) for 30 days in diabetic rats, which was credited to anti-oxidant effects secondary to AMPK activation (mimicked by both Metformin and high dose Vitamin Csupplementation).[91]

5.6. Depression

A mouse study using 5mg/kg Berberine (injection) noted time-dependent reduction in immobility time in a forced swim test, indicative of anti-depressive effects.[82] Berberine was also effective at reversing Reserpine-induced depression (which depletes catecholamines), and enhanced the anti-depressant effects of imipramine, tranylcypromine, fluoxetine, and venlafaxine but not trazodone or mianserine;[82] 10mg/kg fluoxetine (an SSRI) and 5mg/kg Berberine abolished the depressive effects in the forced swim test,[82] and the effect of Berberine (5mg/kg) is as effective as 10mg/kg Imipramine.[82] Anti-depressive effects have been noted following oral administration of 10-20mg/kg in mice, but 100mg/kg (human equivalent dose of 8mg/kg) was ineffective; it underperformed relative to 20mg/kg desipramine, but was synergistic with this one as well.[83]

Berberine appears to exert anti-depressive effects in mice, and appears to work synergistically with a wide variety of standard anti-depressant drugs; oddly, these effects have been observed at 20mg/kg in mice but not at 100mg/kg in mice (equivalent human doses of 1.6mg/kg and 8mg/kg, respectively) No human evidence, however

Oddly, these anti-depressant effects are abolished with injections of 750mg/kg L-Arginine (substrate of which nitric oxide is created) and Viagra (increases nitric oxide in the brain) and was enhanced by inhibitors of nNOS, an enzyme that creates nitric oxide in the brain;[82] this study is duplicated in Medline.[92]

Anti-depressant effects can also be traced back to Sigma receptors, where activation of Sigma receptors σ1 enhances anti-depressive effects and antagonism abolishes the anti-depressive effects.[82][92] Berberine is known as a positive Sigma1 receptor modulator, which is considered a relatively new class of therapeutic options for depression.[93] Sigma receptors are novel intracellular receptors (expressed on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)[94]) and their activation may modulate glutamingeric signalling such as NMDA.[95] They can regulate calcium signalling at both the level of the ER as well as cytoplasm,[96] and a known naturally occurring ligand for S1 receptors is the hallucinogenic N,N-dimethyltryptamine[97] (not to be confused with Hordenine, N,N-dimethyltyramine).

The mechanism of action for Berberine and anti-depression may be via acting as a positive modulator of Sigma-1 receptors (molecular target of the hallucinogen DMT), and enhancing signalling via this receptor; this is likely to occur at rat oral doses of 20mg/kg (preliminary evidence) which correlates to a human oral dose of 1.6mg/kg bodyweight yet may not occur at five-fold the dose (8mg/kg)

5.7. Sedation

Although injections of 2-5mg/kg Berberine fail to alter locomotion, 20mg/kg injections can reduce locomotion in mice[82] (same dose not effective after oral administration[83]). This high dose injection also augmented phenobarbitol-induced sleep time, with lower doses ineffective.[82]

May have sedative properties at higher doses

5.8. Analgesia

A study assessing the analgesic effects of berberine noted that chronic (7 day) treatment of 10mg/kg injections reduced nocioreception in a tail-flick test, with the potency being greater than 10mg/kg Imipramine.[82]

5.9. Alzheimer's Disease

Berberine has been found to have inhibitory potential against Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) with IC50 values of 0.37-0.58uM for AChE[98][99][100] and 3.44uM for BChE.[98] A PANTHER analysis[101] (computer program) noted that another potential targets include Amyloid-β (A4) precursor protein[102] but that assigning Berberine's targets into known pathways yielded 11 targets in the Alzheimer disease-amyloid secretase pathway and 17 targets in the Alzheimer disease-presenilin pathway. [101]

In vitro, Berberine can reduce β-Amyloid levels (APPNL-H4 cells) by 47.1+/-11.5% and 49.1+/-13.6% (Aβ40 and Aβ42, respectively) at 5uM with no further benefit at 50uM[102] possibly secondary to stimulating α-secretory activity (311.9+/-7.9% of control) and downregulating β-secretase (55.5+/-11.1%).[102] The downregulation of β-secretase appears to be secondary to ERK1/2 activation by Berberine.[103]

May beneficially alter the content of β-Amyloid levels in isolated neurons, which is thought to be therapeutic for Alzheimer's Disease. May also have pro-cholinergic effects via enzyme inhibition (also thought to be therapeutic) at a potency that might be relevant in vivo

One rat study using Phellodendron amurense at 100-200mg/kg but with another group injected with 20mg/kg isolated Berberine for 14 days prior to scopolamine injections (anti-cholinergic toxin) was able to attenuate deficits to learning, with an efficacy lesser than 0.2mg/kg tacrine used as active control.[104]

5.10. Neuroprotection

Pretreatment of Berberine in the range of 10nM to 1µM caused dose-dependent cell preservation (up to 65% cell preservation at 1µM) in response to a research oxidative toxin (CoCl2)[105] and survival of neurons has been noted when Berberine injections are given prior to ischemia/reperfusion surgery in rats.[106] Berberine does not cause any cytotoxicity in neurons up to 10µM.[105]

Conversely, when PC12 cells (Pheochromocytoma, used to assess survival and differentiation in vitro) are incubated with 6-OHDA (a pro-oxidative metabolite of dopamine that may induce cell death) and subsequently 10-50µM Berberine, Berberine augments 6-OHDA induced neurotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner.[107] The concept of Berberine augmenting PC12 toxicity in the presence of 6-OHDA has been reported elsewhere,[86] and this has been found in response to CoCl2only when Berberine was applied after the toxin.[105] Pretreatment of a toxin followed by Berberine appears to enhance cytotoxicity, which may be due to Berberine's interaction with the mitochondrial since it interfere with mitochondrial complex I (to activate AMPK[17]) but excessive inhibition of this complex, as is seen with the MPP+ toxin[108] is neurotoxic.

There appears to be a protective effect of Berberine when it precedes toxins (preventative), but Berberine applied after the toxin (therapy) appears to have limited evidence to suggest potentiation of toxicity. This may be due to berberine's main mechanism (inhibition of mitochondrial complex I) inhernetly being hormetic and hormesis not being the smartest thing in instances of cellular damage as is seen with pretreatment of a toxin

When rats were lesioned with 6-OHDA (metabolite of dopamine used in research to mimic Parkinson's Disease lesions) and then subsequently orally treated with 5 or 30mg/kg Berberine (injections) for 21 days, 30mg/kg but not 5mg/kg was associated with less surviving neurons in the substantia Nigra.[107] This mechanism appears to be common to isoquinoline derivatives such as tetrahydropapaveroline, salsolinol, and TIQs.[109]

This adverse effect of Berberine therapy appears to occur in living models

5.11. Addiction and Dependence

One study in morphine dependent mice noted that Berberine (50mg/kg injections) was able to partially normalize the reductions in BDNF mRNA, CRF, and TH expression which predisposed morphine-dependent mice to anxiety and depression.[110] The dose of 50mg/kg Berberine was able to normalize anxiety and depression as was 10mg/kg Fluoxetine, with 10-20mg/kg showing a trend to benefit (not statistically significant).[110]

May attenuate withdrawal from Morphine, may require high doses to do so; no human evidence nor oral consumption evidence currently

6Cardiovascular Health

6.1. Cardiac Tissue

Ischemia-Reperfusion injury in cardiac tissue may be alleviated by Berberine. Rats fed 100mg/kg Berberine daily for 14 days prior to insult (both in vitro testing of cardiac tissue and in vivo testing conducted) Berberine pretreated hearts were associated with preservation of LVDP (75%), LVEDP (29%), +dp/dtma (75%), and −dp/dtmin (69%) without any influence on these parameters per se(without IR injury).[111] Protective effects were noted in vivo as well (LVDP by 9-10% and LVEDP by 40-45%) alongside reduced infarct size and protection from arrythmia; these protective effects are thought to be related to AMPK regulation, with a reduction in AMPK phosphorylation noted in the Berberine IR group.[111] These protective effects have been noted elsewhere with Berberine in diabetic rats[112] and may be related to the structural class rather than being novel to Berberine, as both Coptisine[113] and Palmatine[114] have similar protective effects.

May protect cardiac tissue from Ischemia-Reperfusion (oxidative) injury via AMPK, but the regulatory effects on AMPK are atypical of Berberine's other AMPK-related actions

In regards to cardiac fibrosis, Berberine has once been noted to form G-quadruplexes with the rat relaxin-1 gene promoter region, which attenuated STAT3 downregulation of Relaxin expression (STAT3 is a negative regulator of Relaxin[115]) to 55% of control (20uM) and indirectly promoted mRNA and protein content of Relaxin.[116] Due to Relaxin's role in preventing cardiac fibrosis,[117]Berberine administration (injections) resulted in less fibroblast activation, collagen synthesis, and extent of cardiac fibrosis.[116] Berberine administration appears to promote relaxin in a dose-dependent manner, with 100uM injections increasing Relaxin more than 2.5-fold relative to baseline, and did not inherently influence STAT3 expression nor did it influence nuclear translocation of STAT3 following activation.[116]

May have potential to reduce cardiac fibrosis, but limited evidence with no studies assessing oral Berberine ingestion nor comparison to reference drugs (to assess potency)

Berberine has been shown to have Muscarinic (M2) acetylcholine receptor agonist activities, which has been noted in cultured rat cardiomyocytes where antagonists of the Muscarinic receptor but not beta-blockers abolished the benefits on heart tissue contractility.[118]

These M2 agonist properties may underlie a reduction in heart damage that has been observed, where 150-300mg/kg Berberine was able to attenuate the adverse cardiac effects of a high carbohydrate diet in diabetic rats[119] and may explain how 1.2-2g Berberine daily in persons with cardiomyopathy (in addition to standard therapy) increases Left Ventrical Ejection Fraction and improves quality of life more than placebo.[120]

Berberine also exerts protective effects on the heart after acute injury.[121]

6.2. Triglycerides

30mg/kg Berberine has been found to preserve the protein content of the LDL receptor during periods of inflammation in rats,[122] and may also induce its upregulation via JNK;[123] this is most likely relevant in humans as LDL cholesterol has been shown to be reduced by 25% in hypercholesterolemic persons over 3 months of Berberine ingestion.[65]

Beyond modifying the expression of the receptor, activating ERK can also preserve the constitution of the receptor and stabilize it; leading to a prolongation of the time the LDL receptor can uptake LDL-C into liver cells.[124]

One study investigating proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9; also known as NARC-1 or proprotein convertase 9), an enzyme that degrades the LDL receptor and increases serum LDL as a consequence,[125] noted that Berberine at an oral dose of 10-30mg/kg in rats attenuated the spike in PCSK9 associated with inflammation which was associated with somewhat normalized lipid parameters in blood.[122] PCSK9 is a molecular target connecting inflammation to LDL-C since its expression is positively correlated with inflammation.[126]

The LDL receptor (which takes up LDL from the blood and contributes to an LDL lowering effect) can have its degradation attenuated and its synthesis increased by Berberine by two separate mechanisms; this may underlie the recorded reductions of LDL following Berberine administration to humans which has reached up to 25% in 3 months in people with high cholesterol

Berberine may inhibit lipid synthesis, secondary to the activation of AMPK seen as the main mechanism of action.[127]

Triglycerides have been noted to be reduced 16% following 1g of Berberine ingestion for 4 weeks[2]and 1500mg daily for 12 weeks in otherwise healthy obese persona has noted a reduction of 23%.[128] A placebo-controlled challenge-rechallenge in people with high cholesterol but who were otherwise at low risk for cardiovascular disease also found a statistically significant lowering of triglycerides during the second rechallenge (but not the first) along with a lowering of LDL-C and raising of HDL-C during both phases when compared to placebo; anthropometric measurements and blood sugar were not effected by berberine, although these patients did not have high blood sugar at the start of the trial.[129] A meta-analysis conducted on diabetics (with concurrently high triglycerides) has noted that the reduction of triglycerides averaged 0.48mmol/L with a CI 0.39-0.57, reaching statistical significance.[130]

AMPK activation is a mechanism by which triglycerides can be reduced, which has been reported in humans and appears to be reliable

One meta-analysis has been conducted on diabetic persons that also measured lipid parameters as endpoints, and this meta-analysis concluded significant reductions in Triglycerides (0.48mmol/L reduction; CI 0.39-0.57), Total Cholesterol (0.58mmol/L; CI 0.14-1.02), and LDL-C (0.58mmol/L reduction; CI 0.39-0.78) with an increase in HDL-C (0.07mmol/L increase; CI 0.04-0.10) in these diabetic patients;[130] specifics of the meta-analysis can be reviewed in the Glucose Interventions section.

Appears to have beneficial effects on lipid parameters in Diabetics

6.3. Blood Flow

Berberine is a known vasorelaxant in animals[131][132] and has been used with success in humans.[133]

Appears to have vasorelaxing properties

It is known that berberine works on the endothelium itself and underlying smooth muscle (mostly the former)[134] and it is thought that berberine may work via ACE enzyme inhibition of the NO-cGMP axis[135] or through α1-adrenergic receptor blocking.[136][78] One study has noted that berberine at 25-200µM is able to inhibit ephedrine and histamine induced aortic contractions in a reversible manner yet failed to inhibit contractions from high potassium or caffeine.[137]

6.4. Platelets

Anti-platelet functions have also been noted with berberine, including inhibition of thromboxane synthesis[138] and increased thrombolysis (breaking of clots).[139][133] Other possible mechanisms of action on its anti-thrombotic effects are alpha(2)adrenoceptor agonism on platlets[79] and an inhibitory effect on calcium influx.[140]

6.5. Atherosclerosis

Berberine (10-50uM) can suppress the activity of a protein known as AEBP1, which prevents the uptake of oxidized LDL by macrophages in a dose-dependent manner and attenuates formation of foam cells (artherogenic deposites of macrophages).[141] Suppressing AEBP1 leads to less expression of the scavenging receptors LOX-1 and CD36 and less influx of oxidized LDL (which promotes foam cell formation); CD68 was unaffected by Berberine.[141] Secondary to preventing oxLDL influx, secretion of adhesion factors (proteins secreted from immune cells to promote adhesion) ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are both suppressed.[142]

One study on rats that lacked expression of AMPK noted that the beneficial effects of Berberine on artherosclerosis (including reduced cardiac lesions and oxidative stress) was mostly abolished, suggesting AMPK is critical for cardioprotective effects of Berberine.[143]

7Fat Mass and Obesity

7.1. Mechanisms (Fat Cell Regulatory)

In preadipocytes incubated with 1-10uM Berberine for 3 days during differentiation noted that there was an increase in proliferation (not dose dependent, also seen in mouse adipocytes[144] and 3T3-L1[145]) and suppression of differentiation (dose dependent) up to half suppression at 10uM; post-differentiation, the protein content for LPL, C/EBPα, and PPARγ2 was significantly reduced by more than half and leptin and adiponectin protein content and secretion was significantly reduced.[146] In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, an inhibition of both proliferation and differentiation has been noted at 1.25-5uM, and replicated a suppression of C/EBPα and all three PPAR subsets (α, β/δ, and γ).[145]

Although AMPK is known as the main mechanism of Berberine, it appears that Berberine (3uM) activates an unfolded protein response independent of endoplasmic reticulum stress (vast majority of the time, it is directly linked[147]) which induces activity of CHOP; inhibiting CHOP appears to abolish the reductions in PPARγ and C/EBPα.[148]

In preadipocytes, Berberine appears to suppress differentiation and has mixed effects on proliferation; both studies suggest a reduction in the pro-adipogenic receptor PPARγ (which, oddly, is anti-diabetic when activated)

In mature adipocytes, a suppression of PPARγ is still noted at 1.25-10uM concentration at both the mRNA and protein level; incubation with 10uM Berberine and PPARγ activators (troglitazone and rosiglitazone) demonstrated that PPARγ in inhibitory and reduced the effects by 70-80%.[145] This inhibitory potential extends to PPARα, but to a lesser degree (40-60%), and Berberine was said to notbe a ligand of the PPAR recepetors.[145] This may be related to the aformentioned activation of an unfolding protein response, which induces CHOP activity and suppresses PPARγ and C/EBPα activity; this was noted to also occur in mature adipocytes.[148] The influence of the WNT/β-Catenin pathway has been ruled out.[149]

When cells are taken from diabetic rats (diabetes induced, fed a high carbohydrate diet, then white adipose tissue excised), appeared to reduce TNF-α concentration (-39%) and increase content of all PPAR subsets with the induction of PPARδ and PPARα similar to Fenofibrate and PPARγ similar to Rosiglitazone.[150] These benefits were also seen in another group of rats fed Berberine at 75-300mg/kg for 16 weeks, where both 150 and 300mg/kg outright normalized serum and adipose Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL), serum free fatty acids and TNF-α, and expression of all PPAR subsets and Cyclin T1 (potency was similar to the additive benefits of 100mg/kg fenofibrate and 4mg/kg rosiglitazone).[150]

In mature non-diabetic adipocytes, appears to suppress the activity of PPARy (a protein that is pro-adipogenic). In diabetic adipocytes (confirmed in vivo), Berberine can normalize expression of PPARs that is normally suppressed

Berberine may have anti-lipolytic effects.[151] This study noted that while Berberine did not influence baseline cAMP levels, stimulation of cAMP via PDE inhibitors was attenuated (not abolished) by Berberine; Berberine lessened the inhibitory effects of other compounds, without inherently inhibiting the enzyme action independently of AMPK.[151] This anti-lipoytic effect has been noted elsewhere in 3T3-LI adipocytes where lipolysis was stimulated by IBMX, forskolin and 8-bromo-cAMP.[152]

Berberine may induce HSL activity (a pro-lipolytic effect) via an AMPK independent manner.[151]

Theoretically possible that Berberine can reduce the fat burning effects of PDE inhibitors (luteolin, resveratrol) and forskolin (active ingredient in coleus forskohlii)

7.2. Mechanisms (Glucose Related)

In regards to adiponectin, an adipokine (signalling molecule derived from fat cells) that plays a positive role in insulin sensitivity (is secreted, and then acts on tissue via its receptors to activate AMPK[153]) and is reduced in diabetics, particularly the high activity structure.[154] Adiponectin is found in three structural forms (trimer, hexamer, and high molecular weight) with the latter being the most related to insulin sensitivity;[155] Berberine (2-4uM) acts through AMPK activation, particularly the AMPKα1 subset, to increase the percent of adiponectin in high activity structure; a process known as adiponectin multimerization.[156] This was also noted with AICAR, a research drug used to activate AMPK, suggesting a general effect that is not unique to Berberine;[156] this intricate loop (Adiponectin activating AMPK which promotes high-activity adiponectin) is a mechanism of adiponectin self-regulation.[157]

It should be noted that studies using Berberine in predifferentiated adipocytes noted less secretion of adiponectin which was the natural consequence of suppressing differentiation.[146] This was also replicated in the aforementioned study on enhancing adiponectin function, with both phenomena occurring at similar concentrations.[156]

Appears to enhance the activity of adiponectin, but practical relevance of this mechanism for insulin sensitivity is unknown

Berberine is known to enhance glucose uptake into fat cells, and at 25uM concentration it is equally potent as 15uM 2,4-thiazolidinedione (TZD, an anti-diabetic drug, by 3.3 fold) and slightly outperformed both arecoline (3.2 fold) and vanillic acid (2.9 fold), natural products.[158] This study also noted that Berberine acted synergistically with both TZD and Metformin.[158] Berberine has also been shown to be more effective at enhancing glucose uptake than polysaccharides from Astragalus Membranaceus.[159]

Although AMPK activity increses by Berberine is known to increase glucose uptake into adipocytes,[160] Berberine seems to act independently of AMPK to increase glucose uptake by 5-fold in L929 fibroblast cells that only express GLUT1 transporters; Berberine was found to increase the activity of GLUT1 (a normally low-active glucose transporter, with GLUT4 being the major one) via a partially p38 MAPK and ERK dependent pathway.[161] This increase in GLUT1 activity has been noted elsewhere in adipocytes (3T3-L1), although attributed as secondary to AMPK activation.[162]

Berberine may also inhibit the PTP1B enzyme and promote glucose uptake into adipocytes (and myocytes) by preserving the actions of insulin. At concentrations of 1.25-2.5uM Berberine, insulin receptor phosphorylation is increased without affecting protein content.[160] The IC50 of Berberine on PTP1B appears to be 156.9nM and a Ki value of 91.3nM, remarkably potent.[163]

Berberine has been found to partly normalize the decrease of glucose uptake induce by palmatate (a fatty acid), which is through anti-inflammatory effects in inhibiting increased activity of IKKβ and NF-kB; which subsequently increase IRS-1 and reduce glucose uptake via the insulin receptor.[164] This anti-inflammatory effect has been noted elsewhere when measuring cytokines,[165] and fatty-acid induced insulin resistance has also been replicated elsewhere related to NF-kB.[166]

Multiple mechanisms of increasing glucose uptake into fat cells, despite inhibting their proliferation. Augments insulin-dependent glucose uptake (PTP1B), insulin-indepenendent glucose uptake (AMPK), increasing the affinity of low-activity glucose transporters (GLUT1), and attenuating insulin resistant effects

7.3. Interventions

One study in persons with newly diagnosed metabolic syndrome noted that 300mg Berberine thrice a day (900mg total) for 12 weeks was associated with a significant reduction of BMI from 31.5+/-3.6 to 27.4+/-2.4 (average 13% decrease) with a significant decrease in waist circumference by 5.5%; lean mass and fat mass were not measured.[146] Otherwise healthy but obese persons taking 500mg Berberine thrice daily (1500mg total) for 12 weeks without adjustments to exercise noted reduction in body weight of approximately 5lbs (2.3% body weight; 3.6% body fat); food intake was not changed overall, but two subjects reported a decrease in appetite.[128]

Another trial in humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease who were given either lifestyle interventions alone, or lifestyle interventions plus 15mg pioglitazone daily or 0.5mg berberine thrice daily for 16 weeks found a significant reduction in BMI of 1.51 in the berberine group compared to a 0.72 reduction in BMI with lifestyle interventions alone; pioglitazone had a reduction similar to lifestyle interventions alone.[167]

Not too much evidence in humans, but some studies confirm weight loss with one suggesting a very slight preference for fat loss based on percentages; seemingly more potent in unhealthy persons, no studies in persons of normal weight yet.

8Interactions with Glucose Metabolism

Note: For a comprehensive review of how Berberine can interact with glucose metabolism, the sections on the Liver and the Pancreas (under 'Interactions with Organ Systems') should be reviewed, as should subsections in both the section on Fat Mass and Skeletal Muscle Metabolism that mention glucose. These four sections contribute to the potent anti-diabetic effect of Berberine

8.1. Absorption

Berberine appears to weakly suppress glucose uptake acutely,[23] with 72 hours of incubation suppressing glucose uptake to a statistically insignificant degree in vitro.[168]

Sucrase is inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner with an IC50 of 1.83mg/L (fairly low potency)[23] ot 0.28mg/mL.[169] The sucrose-isomaltase (SI) enzyme complex appears to have its mRNA increased in the state of diabetes, which is reduced (to up to 62% that of control rats) at 100-200mg/kg Berberine for 35 days, this affected non-diabetic rats as well.[170] Another study using 125mg/kg Berberine for 33 days noted that, in response to an oral sucrose tolerance test, that Berberine resulted in 43% less AUC for glucose in serum (less efficacy than 20mg/kg Arcabose as active control) which correlated with less sucrase activity in all parts of the intestines.[169] 100mg/kg Berberine for 4 weeks has been reported to have similar effects elsewhere.[171]

Maltase appears to be inhibited but not in a dose-dependent manner,[23] with another study suggesting the alterations of Maltase activity seen in diabetic rats (1.45-2.56 fold increase) being normalized with 35 days of supplementation of Berberine (100-200mg/kg)[170] and mostly normalized in all areas of the intestines after 125mg/kg for 33 days.[169] There does not actually appear to be any direct inhibition of active maltase enzymes up to 50uM of Berberine (somewhat contested, another study suggests an IC50 of 0.11mg/mL[169]), but 5 days of exposure to this concentration reduces activity by 48% in vitro.[170]

Lactase (mediates digestion of lactose) is also increased in the state of diabetes and attenuated, but not normalized, following ingestion of 125mg/kg Berberine for 33 days in rats.[169]

In regards to alpha-amylase (mediates starch digestion), Berberine has been tested in an in vitroinhibition test for fungal amylase noted dose-dependent growth inhibition with Ki values similar to Chlorogenic Acid and Caffeic acid and suggested non-competitive inhibition of the enzyme itself.[172]

The downregulation of enzyme activity (Maltase and SI complex) appears to be partly PKA dependent, and inhibiting PKA with the inhibitor H89 attenuates (but does not abolish) these effects.[170]

Direct inhibition of carbohydrate digestive enzymes appears to be either weak or non-existent. Prolonged treatment of Berberine may cause a reduction in synthesis of the enzymes that mediate sugar absorption (lactose, sucrose, and maltose) with possible but currently unexplored direction inhibition of the enzyme mediating starch absorption

Studies that compare the potency of Berberine to the reference drug, Arcabose, suggest that it is slightly (statistically significant) less potent

8.2. Interventions

The hypoglycemic effect of Berberine was first discovered in 1988 when a hypoglycemic effect was accidentally noted in diabetic patients when Berberine was given for anti-diarrheal effects.[173]

One Meta-Analysis has been conducted on Berberine has been conducted as it pertains to Type II Diabetes.[130] This Meta-Analysis noted 14 trials (all originating from China) including 1068 patients between the years of 2007-2011 and noted that Berberine at 0.5-1.5g daily paired with lifestyle intervention over 12 weeks was associated with improvements in Fasted (0.87mmol/L reduction; CI 0.54-1.20) and Postprandial (1.72mmol/L reduction; CI 1.11-2.32) blood glucose and HbA1c (0.72% reduction; CI 0.47-0.97%) with improvements in lipid metabolism and a reduction in Fasting Insulin Levels (0.5mU/L; CI 0.03-0.96).[130]

7 Trials (of 448 patients) used comparative assessment against oral hypoglycemic agents and, although a meta-analysis could not be performed due to heterogeneity of data, that there did not appear to be any significant differences when Berberine was compared against Metformin, glipizide, or rosiglitazone.[130] In 4 out of 6 trials that used Berbering as adjuvant treatment alongside oral hypoglycemics, additive benefits were found to be significant with Fasting (0.59mmol/L reduction; CI 0.35-0.83) and Postprandial (1.05mmol/L reduction; CI 0.48-1.62) blood glucose as well as HbA1c (0.53% reduction; CI 0.11-0.95%) dropping more in combination therapy than with oral hypoglycemic drugs alone.[130]

Methodology of the included studies was deemed subpar (Jadad score less than 3) but there did not appear to be risk of bias as assessed by funnel plot (although due to less than 10 studies being used, funnel plot may not have been as accurate as desired[174]).[130] This meta-analysis excluded three studies (none of which are indexed online) due to differences at baseline or uncertainty in randomization.[130]

Other trials on Berberine note that 0.3g thrice a day (900mg total) for 12 weeks in 37 persons with newly diagnosed metabolic syndrome noted significant reductions in blood glucose (17%), HbA1c (15%), fasting insulin (26%), and insulin sensitivity assessed by HOMA-R (41%).[146] Type II Diabetics given 1g Berberine for a month experiencing 20% and 26% reductions in fasting and postprandial blood glucose alongside a 12% reduction in HbA1c, but only a slight trend to improvement in insulin sensivity.[39] 1g Berberine over 2 months reducing fasting blood glucose (25.9%), HbA1c (18.1%), and triglycerides (17.6%).[175] Another trial in humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease who were given either lifestyle interventions alone, or lifestyle interventions plus 15mg pioglitazone daily or 0.5mg berberine thrice daily for 16 weeks found no difference between the 3 groups in HbA1C, but did find improved HOMA-IR scores in the berberine plus lifestyle interventions group compared to lifestyle interventions alone, with no difference versus lifestlye interventions plus pioglitazone.[167] Area under the glucose curve after an oral glucose tolerance test was also reduced in the berberine group compared to lifestyle interventions alone (with again no difference versus pioglitazone), primarily due to stronger glucose lowering at the 120 and 180 minute mark.[167] Similar improvements were found in people with the metabolic syndrome, where 0.5g of berberine three times a day for three months resulted in improved insulin sensitivity as measured by the insulinogenic and Matsuda indices, glucose AUC glucose, and insulin AUC versus placebo.[176]

Comparative studies using Berberine note that 1g daily find that it is equally effective at improving measured parameters (usually fasting blood glucose, insulin, HbA1c, and triglycerides) when compared to Metformin[177][175] and Rosiglitazone[175] when they are used within the standard dosage range of 1.5g (Metformin) or 4mg (Rosiglitazone).

Appears to be beneficial for blood glucose control in diabetic persons, and the potency of 0.5-1.5g daily does not appear to be significantly different than standard anti-diabetic pharmaceuticals and may be additive

9Skeletal Muscle and Physical Performance

9.1. Mechanisms (Glucose Related)

Berberine has been shown to stimulate glucose uptake into skeletal muscle[178] partially via AMPK mediated effects.[179]

AMPK activation can increase mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle cells, which Berberine has been shown to do; the inactivity of Berberine in cells lacking SIRT-1 (a required intermediate) has been established.[180]

Appears to increase glucose uptake and mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle cells via AMPK

The inhibition of PTP1B, which promotes insulin receptor signalling with an IC50 of 156.9nM,[163] also appears to occur in muscle cells.[160]

Berberine appears to induce glucose uptake into muscle cells by itself whether the muscle cell is insulin resistant[181] or insulin sensitive,[62] but a synergistic interaction between insulin and Berberine only exists when the muscle cell is insulin resistant, with insulin sensitive cells being barely additive (additive effects not statistically significant, there appears to be crossover in the mechanisms).[181][62]

The upregulation of the insulin receptor protein content (amount of insulin receptor expressed on the cell surface) appears to extend to L6 rat myocytes at 7.5uM to 2.5-fold that of control, with significant but lesser benefits noted at 2.5uM.[182] This was due to increasing transcription of the receptor at the genomic level, and is PKC dependent, which Berberine appears to dose-dependently activate.[182]

Can enhance both the expression of the insulin receptor and improve its signalling (via PTP1B inhibition), fairly potent at the latter in a nanomolar range. PKC and its subset PKCζ (zeta) appear critical in the potentiation and preservation of insulin signalling as well

9.2. Mechanisms (Proliferation and Differentiation)

Berberine (5mg/kg injections) has been found to induce muscle protein atrophy in mice by stimulating breakdown and inhibiting synthesis, an increase in atrogin-1 appeared to mediated these effects, and was independent of Akt/PI3K and FoxO alterations but found to be related to AMPK activation[61] which is known to increase Atrogin-1.[183] The induction of muscle protein breakdown was mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system and the attenuating of muscle protein synthesis by reducing content of eIF3-f; both of these effects were abolished by Atrogin-1 siRNAs, suggesting that this protein (induced by Berberine) is causative.[61]

The increase of Atrogin-1 may also be partly mediated by mitochondrial stress, as overexpression of PGC-1a prevents Berberine-induced Atrogin-1 release.[61] Berberine has been found to interfere with complex I of the mitochondria, and augment protein uncoupling (UCP2,3)[63][17] and this interference is the same thing that underlies AMPK activation from Berberine (as well as Metformin).[17][58] When the Myotubes were overexpressing PGC-1α, the decrease in myocyte diameter was abolished as was the increase in AMPK activation.

AMPK activation appears to lead to suppressed Myocyte growth, which is mediated by Atrogin-1 induction; overexpression of PGC-1α prevents this, but may abolish the AMPK induction. Abolishing Atrogin-1 reverses suppression into hypertrophy. Limited evidence all around

10Skeleton and Bone Metabolism

10.1. Calcitriol

A study in healthy obese subjects given 500mg Berberine thrice a day (1500mg total) for 12 weeks noted a trend (p=0.11) to increase serum calcitriol was seen in all subjects by 59.5%; this increase in the hormonally active form of Vitamin D was not tested in the concomitant rat study and the influence of seasonal changes cannot be ruled out.[128]

10.2. Joint Inflammation

In vitro with synoviocytes (proliferation of which is involved with pathology of Rheumatoid Arthritis), Berberine was able to inhibit cell proliferation at G0/G1 phase (thought to be from reducing mitochondrial membrane potential).[184] In chondrocytes, Berberine was able to attenuate MMP concentrations (seen as being involved in osteoarthritis[185]) and increase TIMP-1 at 25-100uM, which worked against IL-1b actions and exerted an anti-osteoarthritic effect; 50uM showed almost normalization of these levels to control values.[186]

Shows mechanisms that could aid both Rheumatoid and Osteoarthritis, moderately potent

In a rat model of adjuvant-induced Arthritis, 10mg/kg Berberine (injected) daily 9 days was able to attenuate the paw edema (marker of disease progression) in mice while a shorter supplement time frame of 3 days exerted nonsignificant benefit and irregular injections actually exacerbated paw edema.[187] An acute injection of 50-100uM Berberine into a rat knee three hours prior to inflammatory insult was able to abolish the effects of IL-1b at 100uM Berberine.[186]

Highly potent anti-inflammatory effects, but the animal models use injections; not known how oral ingestion affects joint health

11Inflammation and Immunology

11.1. Inflammation (General)

Oral ingestion of Berberine for 4 weeks can dose-dependently reduce the serum rise of 8-isoprostane in response to the pro-inflammatory LPS, with oral ingestion of 30mg/kg effectively abolishing the LPS-induced rise in 8-isoprostane.[122] The LPS-induced increase of TNF-α (53-86%), IFN-γ (74-88%), and IL-1α (68-93%) was also attenuated with 10-30mg/kg ingestion of Berberine.[122]An attenuation of these proinflammatory biomarkers has also been noted in response to dextran sulfate sodium (research chemical to induce colitis)[188] and in response to TNBS-induced colitis, where the degree of cytokine reductions following 20mg/kg reached 100% (TNF-α), 78% (IL-1β), and 98% (IL-6) while the levels of IL-10 (reduced to 11% in colitis control) had the reductions attenuated to 53%.[189]

Chronic ingestion of Berberine appears to be associated with less inflammation in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli.

When looking at the interaction of Berberine and Cyclooxygenase enzymes, Berberine does not interact with COX1 or COX2 at concentrations up to 100uM.[190]

11.2. Macrophages

Acutely, Berberine incubation with RAW264.7 macrophages that are stimulated with LPS (proinflammatory agent) appears to have an IC50 value in inhibiting nitric oxide release of greater than 30uM (weak effect).[191]

Has not yet been demonstrated to have effective anti-inflammatory effects in acute studies on macrophages

Berberine (10-50uM; concentrations below 75uM are nontoxic[192]) can suppress the activity of a protein known as AEBP1, which prevents the uptake of oxidized LDL by macrophages in a dose-dependent manner and attenuates formation of foam cells (artherogenic deposites of macrophages).[141] Suppressing AEBP1 leads to less expression of the scavenging receptors LOX-1 and CD36 and less influx of oxidized LDL (which promotes foam cell formation); CD68 was unaffected by Berberine.[141] Suppression of LOX-1 and another scavenger receptor, SR-BI, were noted to nearly control levels at 5-10mg/L Berberine over 24 hours incubation with no effect on ABCA1.[193]

This inhibition of oLDL uptake may also prevent other consequences of oLDL uptake, such as MMP9 secretion and NF-kB activation in macrophages.[192]

May prevent macrophages from becoming foam cells, which is a consequence when they absorb oxidized LDL (an acutely protective effect, but over time makes the foam cells themselves become plaque in arteries)

11.3. T-Cells

Berberine at 10-20mcg/mL concentrations in vitro appears to slightly enhance T-cell proliferation in response to antigens, while concentrations above that show dose-dependent immunosuppression.[187]

Berberine appears to be an selective inhibitor of JAK3 with 20-fold more affinity for JAK3 than JAK2 (with no apparent affinity for JAK1),[194] the JAK3/STAT pathway being one that induces a fair bit of inflammation from cytokines in models of arthritis and mediates immunology (inhibition of which is a novel class of immunosuppressants).[195][196] Berberine can inhibit IL-2 induced signalling via JAK3 with an IC50 of 3.78µM and the IC50 on JAK2 was 80µM, and in vitro at 3µM Berberine nuclear activity of JAK3 (via STAT5) is mostly undetectable.[194] The mechanism of inhibition appears to be from blocking JAK3 kinase activity at the ATP-binding site.[194]

May mediate immunosuppression via being a selective JAK3 inhibitor

11.4. Virology

A study using the virological strain PR/8/34 (Influenza A) and WS/33 (H1N1) noted that its replication in macrophages (immune cells) was suppressed with 25uM Berberine, which extended to A549 human epithelial cells (potent suppression) but not MDCK cells.[197] The suppression with Berberine had IC50 values of 0.01μM and 0.44μM for these respective viral strains, which outperformed the reference drug amantadine.[197]

12Interactions with Oxidation

12.1. Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a cellular cytoskeleton extending from the nucleus into the cytoplasma; it is sensitive to changes in oxidation and calcium influx and has an 'ER stress response' to maintain homeostasis known as the unfolded protein response.[198]

In cancer cells, Berberine has been at times noted to induce apoptosis secondary to activating an ER stress response (IC50 160mcg/mL in T98G Glioblastoma cells,[199][200] cervical,[201] oral,[202] variable range of 10-100uM in other cancer cell lines[203]).

In other cells, Berberine appears to attenuate inflammation-dependent ER Stress in endothelial cells where apoptotis was 95% reversed at 20uM[204] and was noted to suppress the induction of GRP78/BiP (correlated with ER stress) and less caspase-3 (released from mitochondria after stress to induce apoptosis).[204] HepG2 (liver) cells have also noted an attenuation of ER stress,[205] and a study in mouse macrophages incubated with HIV has also noted a dose-dependent reduction of ER stress.[206]

There appears to be regulatory aspects of Berberine on the the endoplasmic reticulum, inducing oxidant stress in cancer cells while attenuating oxidant stress under some conditions in healthy cells. Exact mechanisms mediating this regulation not yet characterized

12.2. Lipid Peroxidation

In an ex vivo assay of lipid peroxidation, Berberine inhibited lipid peroxidation directly with an IC50 of 72μM, and was found to be active in TNBS-induced colitis in reducing lipid peroxidation in the colon.[189] Lipid peroxidation has also been shown to be reduced in the β-cells of the pancreas following oral ingestion of 150-300mg/kg bodyweight.[207]

Appears to be a direct anti-oxidant, but is quite weak at directly preventing lipid peroxidation; appears to be much more potent in living systems, and possibly not mediated by direct effects

13Interactions with Hormones

13.1. Testosterone

Due to interactions with CYP3A4 (inhibition of which may increase testosterone) and CYP1A2 (Aromatase),[49] it is theoretical that Berberine may increase circulating testosterone levels; this is currently untested in living systems.

Theoretical testosterone boosting properties that are currently not demonstrated

13.2. Estrogen

The incubation of Tamoxifen (1.5uM) and Berberine (16ug/mL) in estrogen responsive MCF-7 breast cancer cells is able to synergistically increase apoptosis.[208] This synergism seems to be related to estrogen receptor antagonists in general, although the mechanism(s) exerted by Berberine is/are currently not known.[208]

13.3. Leptin

One intervention on people newly diagnosed with metabolic syndrome noted that 300mg Berberine taken thrice a day (900mg total) for 12 weeks was able to reduce circulating leptin levels 36% while nonsignificantly raising adiponectin, but the leptin/adiponectin ratio improved from 0.76 to 0.58.[146]

13.4. GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a peptide hormone known to be secreted from the gut that has blood glucose lowering properties, in part through stimulating insulin secretion[209][210] and may also have a role in proliferating pancreatic β-cells.[211] Berberine has been found to, at the oral dose of 120mg/kg for 5 weeks, increase both GLP-1 and insulin concentrations in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats (measured postprandially).[212] This study also noted an increase in β-cell population (460% of diabetic control, but still less than half of nondiabetic control) which was attributed to GLP-1.[212]

14Cancer Metabolism

14.1. Mechanisms (General)

Multiple targets exist which may explain anti-cancer effects of berberine. Berberine is known to directly bind to DNA, which is one mechanism by which it can cause cell cycle arrest in multiple human cell cancer lines in vitro,[15] although upregulation of GADD153, a transcription factor involved in apoptosis, may also play a role and has been seen to accompany cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in a human cervical cancer cell line.[201] This mechanism has been observed in one case to occur through downregulating death-domain-associated protein, a key protein which regulates pathways related to cell survival, by binding to its promoter region, which led triggered a cascasde ultimately leading to cancer cell death.[213] Berberine also has been seen to interfere with DNA synthesis in growing ovarian cancer cells by inhibiting two key enzymes in this pathway, dihydrofolate reductase and thymidylate synthase.[214]

Berberine also seems to supress the expression of certain proteins which are anti-apoptotic in cancer cells, such as Mcl-1.[215] Berberine can also affect telomerase activity through multiple mechanisms as well, including the downregulation of the chaperone protein nucleophosmin,[216]through inhibition of human telomerase reverse transcriptase, an essential component of human telomerase,[217] or perhaps even through direct interaction with telomeric DNA.[74]

Another possible mechanism of berberine's efffect on cancer is via JAK3 selective inhibition, as at least one study has noted that berberine could decrease viability in cancer cell lines overexpressing active JAK3 (Ba/F3-JAK3V674A and L540) while not having a significant effect in other cell lines (HDLM-2 and DU145) at the same concentration of 3uM.[194]

Several plausible molecular mechanisms exist which suggest berberine may have anti-cancer effects.

14.2. Proliferation and Angiogenesis

Berberine seems to act as an antiproliferative in several cancer cell lines in vitro through the induction of apoptosis.[15] The main pathways which berberine exerts its antiproliferative effects include the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, the HER2/PI3K/AKT pathway, the JNK/p38 redox/ROS pathway, and NF-kB, depending on the cell line.[15]

While direct effects on angiogenesis of tumor cells by berberine have not been observed, berberine is known to suppress Mcl-1 in at least one cell line in vitro, which is known to have angiogenic effects.[215]

14.3. Migration and Metastasis

The migration of a human tongue squamous cell carcinoma line has been shown to be reduced by berberine in vitro, and involved the inhibition of several proteins including NF-κB, MMP-2, and MMP-9.[218] Similar effects have been seen in a human lung cancer cell line.[219]

Injection of berberine into a mouse model of metastatic melanoma inhibited tumor nodule formation; the mechanism for this was an associated downregulation of matrix metalloproteases by negatively regulating ERK1/2.[220]

In vitro studies as well as one in vivo mouse model study suggest that berberine may exhibit anti-metastatic effects.

14.4. Autophagy

Autophagy is the process a cell undergoes to degrade cellular components and to produce energy, usually under times of nutrient deficiency.[221] Its relationship to cancer is complex, as a loss of the ability of autophagy could make cells cancerous by knocking out caspase-independent autophagic, or type II, cell death; parodoxically, however, autophagy may also promote tumor survival by giving cancer cells a growth advantage.[221]

Berberine has been shown in vitro to induce autophagic cell death in human liver cancer cells through the distinct increase in Beclin-1, which is one of the main proteins involved in this pathway, as well as an inhibition of mTOR (through MAPK activation and AKT inhibition), which is one of the main regulators of this pathway.[222] Berberine, at least when combined with radiation, has been shown to induce autophagic cell death in lung carcinoma cells, which also led to tumor shrinkage in a xenograft mouse model.[223]

In addition to inducing classical apoptosis, beberine also may induce autophagic cell death in some cancer cell lines.

14.5. Adjunct Therapy Potential

Berberine has been found to enhance the cytotoxicity of Doxorubicin (a chemotherapeutic agent), where cytotoxicity of Doxorubicin was enhanced with a Combination Index[224] of 0.61-0.73, denoting synergism.[225] This study noted that the IC50 values on growth inhibition with Doxorubicin were enhanced from 3.1 and 16.7uM (A549 and HeLa cells) to 1.7 and 1.9uM despite Berberine being relatively weak.[224] Berberine (60mg/kg) has also been found to reduce the hepatotoxicity of Doxorubicin in rats, attenuating the increase in ALT and AST and reducing Doxorubicin-induced liver necrosis by 28%.[226]

14.6. Brain

Berberine has been seen to inhibit the growth of human neuroblastoma cells which express p53 at concentrations of 5μM-100μM in vitro, with cells not expressing this protein being much less sensitive (IC50 > 100μM), suggesting that p53-induced apoptosis in these cells.[227] Berberine also induced apopotosis in glioblastoma cells in vitro with an IC50 of 134μg/mL through the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway.[228]

14.7. Breast

Berberine induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells in vitro at 25μM through the mitochodrial/caspase-dependent pathway.[229]

14.8. Liver

In HepG2 cells and metastatic liver cells MHCC97-L (as well as nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines HONE1 and HK1) appears to induce cytotoxicity with IC50 values at 100uM (HepG2) and 250uM (MHCC97-L) via autophagy, as abolishing Atg5 attenuates cytotoxicity.[222] Berberine was noted to dose-dependently increase staining for autolysosomes and autophagosomes, which may be due to induction of Beclin-1 (which binds to and sequesters Bcl-2,[230] a mitochondrial membrane protection protein; reducing Bcl-2 indirectly promotes autophagy[231]) and lead to cancer cell death via mitochondrial capsase release.[222] A dose-dependent inactivation of mTOR was also noted with Berberine, thought to be downstream of Akt.[222]

14.9. Oral

Berberine at 1-100uM concentration can suppress COX-2 induction in stimulated oral cancer cells (OC2 and KB) secondary to inhibiting the ability of AP-1 to induce their induction; Berberine does not directly interact with either COX-1 or COX-2.[190]

14.10. Thyroid

Berberine has been found to inhibit thyroid cancer cells growth in vitro using the cell lines 8505C and TPC1 (anaplastic and papillary, respectively).[232] This study noted dose-dependent reductions in cell proliferation with an IC50 of 10uM, and was involved with inducing apoptosis at G2/M and G0/G1 for 8505C and TPC1 cells, respectively, modulated by increased expression of P27.[232]

14.11. Colon