THE BIG FAT SURPRISE: A CRITICAL REVIEW; PART 2

Introduction to Part Two

Note: I am actually publishing part two of my critique prior to part one for reasons that have nothing to do with anything.

The Big Fat Surprise (BFS) by Nina Teicholz is yet another book in a long line of books that informs the reader that everything you thought you knew about nutrition is wrong: saturated fat from animals is actually quite good for you, cholesterol isn’t really important, the government lied to you, nutritionists and dietitians lied to you, the American Heart Association lied to you, etc… Leaving aside that the concept of that kind of a conspiracy actually existing is really absurd, what I’m surprised about is that publishers can keep churning out books like this and people are gullible enough to keep buying them.

There wasn’t even much of a positive case for why, as Teicholz states in her subtitle, butter, meat, and cheese belong in a healthy diet. Even in Chapter 10, which is titled Why Saturated Fat is Good for You, there was hardly any evidence of why saturated fat is good for you. The bulk of the chapter — and indeed the book — instead focused on why a low-fat diet is not good for you. Of course she can poke all the holes she wants into a low-fat diet, but that still does not make a case for a high-fat diet, much less a diet high in butter, meat, and cheese. She still has all her work ahead of her.

This brings me to another problem with the book, and perhaps the low-carb community in general. Teicholz reduces the multiplicity of diets that exist in the world to a low-fat or high-fat dyad. To say that this kind of dietary binarism is myopic would be an understatement. This thinking really overlooks the complexity of diets and, in my opinion, totally ignores the kinds of issues that make nutrition science so interesting: issues like bioactive compounds, the gut microbiome, and nutritional epigenetics to name a few.

Unfortunately there are quite a few instances of inaccuracies in the book ranging from simple citation errors to deliberate misrepresentations of scientific studies to outright plagiarism. These are bold claims that I am leveling against the author. I don’t take these lightly, and I stand by them. I have checked many of her references and the results of my efforts are below. If I have made any mistakes please inform me in the comments. Furthermore, if you would like to go to the source and view the original text please let me know and I will provide the publication.

Chapter 6: How Women and Children Fare on a Low-Fat Diet

Page 136

Jerry Stamler expressed in 1972, that fat was “excessive in calories… so that obesity develops.” This seemingly obvious but nonetheless unproven assumption was that fat made you fat.

If you actually read the cited paper you will note that Stamler was not referring to fat when he said that, he was instead referring to the “habitual diet of Americans.”1 Stamler’s quote is taken out of context and put into a different context that is inaccurate.

* * *

Cribbing Taubes Alert

Teicholz seemingly copy-pastes Taubes work on page 136 when she discusses an amazingly obscure 1995 pamphlet by the American Heart Association. According to Teicholz the pamphlet:

told Americans to control their fat intake by increasing refined-carbohydrate consumption. Choose “snacks from other food groups such as . . . low-fat cookies, low-fat crackers, . . . unsalted pretzels, hard candy, gum drops, sugar, syrup, honey, jam, jelly, marmalade” […]

Leaving aside the fact that the pamphlet never actually advises anyone to increase their refined-carbohydrate consumption, what’s interesting is that Taubes says the very same thing in chapter sixteen of WWGF:

[T]he AHA counseled, “choose snacks from other food groups such as … low-fat cookies, low-fat crackers … unsalted pretzels, hard candy, gum drops, sugar, syrup, honey, jam, jelly, marmalade (as spreads).”

The ellipses are even in the same place! What a coinkydink.

She goes on to say:

In short, to avoid fat, people should eat sugar, the AHA advised.

No. That’s a gross and highly misleading oversimplification. There’s no way you can distill 20 pages of dietary advice into “eat sugar” and think you’re even approaching a decent approximation.

* * *

Page 138:

Jane Brody, the health columnist for the New York Times and the most influential promoter of the low-fat diet in the press, wrote, “If there’s one nutrient that has the decks stacked against it, it’s fat” […]

That quote does not appear in the cited NYT article.2

* * *

On page 143 Teicholz attempts to make the argument that plant-based diets aren’t all they’re cracked up to be:

Vegetarian diets generally have not been shown to help people live longer. The 2007 report by the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research, discussed in the last chapter, found that in no case was the evidence for the consumption of fruits and vegetables in the prevention of cancer “judged to be convincing.”

This has got to be one of the most selective and misleading interpretations of the Second Expert’s Report. I mean, my god… So for those who are not familiar with it, the Second Expert’s Report (what Teicholz discusses above) is an incredible text that outlines ALL of the quality evidence on a given cancer topic regarding food, nutrition, and the prevention of cancer. All the evidence is evaluated by a large panel of elite doctors and researchers and given one of the following labels: unlikely, suggestive, probable, and convincing. To reach the convincing level you really need some rock solid evidence.3 None of the evidence regarding fruits and vegetables reached the venerable convincing level, but there was a ton of probable and suggestive evidence for many cancers. You really have to scour that section to find a quote that might fit an anti-vegetable narrative. Read it yourself for all the juicy details, but here are some remarks from the conclusion on page 1144:

Non-starchy vegetables probably protect against cancers of the mouth, pharynx, and larynx, and those of the oesophagus and stomach. There is limited evidence suggesting that they also protect against cancers of the nasopharynx, lung, colorectum, ovary, and endometrium. Allium vegetables probably protect against stomach cancer. Garlic (an allium vegetable, commonly classed as a herb) probably protects against colorectal cancer.Fruits in general probably protect against cancers of the mouth, pharynx, and larynx, and of the oesophagus, lung, and stomach. There is limited evidence suggesting that fruits also protect against cancers of the nasopharynx, pancreas, liver, and colorectum.

* * *

On page 144 Teicholz derides the study that low-carbers love to hate, T. Colin Campbell’s China Study:

These books are based on one epidemiological study, with a number of significant methodological problems, that was never published in a peer-reviewed issue of a scientific journal. Campbell’s two papers were instead published as part of conference proceedings in journal “supplements,” which are subject to little or no peer review.

As evidence she cites a BLOG POST by then-undergraduate Chris Masterjohn, published by a private organization that is explicitly biased in favor of animal-based diets.5 Just let that sink in…

* * *

After discussing the Ornish diet for a bit, Teicholz mentions a paper on page 145 that reviews the evidence for (very) low-fat diets:

Tufts University nutrition professor Alice Lichtenstein and a colleague reviewed the very low-fat diet for the AHA […] Lichtenstein concluded that very low-fat diets “are not beneficial and may be harmful.”

Teicholz both takes the quote out of context and mangles it somewhat. Here’s the actual quote (emphasis mine):

At this time, no health benefits and possible harmful effects can be predicted from adherence to very low fat diets in certain subgroups.

The “in certain subgroups” part is vital to the accuracy of the statement. You can’t just cut it out. And Dr. Lichtenstein’s conclusion is quite a bit more nuanced than Teicholz would have you believe. The paper is actually a very objective look at low-fat diets.6 It acknowledges that more research needs to be done on these diets in order for a definitive recommendation. Moreover, as alluded to above, it states that until more evidence comes in young children, the elderly, pregnant women, and those with eating disorders should probably avoid the diet. However, it also acknowledges that a low fat diet can be beneficial and there is evidence for that. Here’s an actual quote from the conclusion:

There is overwhelming evidence that reductions in saturated fat, dietary cholesterol, and weight offer the most effective dietary strategies for reducing total cholesterol, LDL-C levels, and cardiovascular risk.

* * *

On page 146 Teicholz discusses the idea of reducing cholesterol levels In young children:

Indeed, in the late 1960s, the NHLBI had been putting children as young as four years old on cholesterol-lowering diets and also giving them cholestyramine, the same drug that would be used in the LRC trial. Convinced that cholesterol was a crucial part of the heart disease puzzle, the NHLBI went so far as to propose universal umbilical cord blood screening in order to start treatment as early as possible, even at birth. In 1970, mass screening of cord blood at “no more than” five dollars per baby was given serious consideration. Such was the preoccupation with heart disease that researchers believed healthy children ought to start out life in a position of defense.

These people are obsessed with cholesterol! Won’t somebody pleeease think of the children??Of course to the average person reading this it sounds absurd, and it would be absurd if Teicholz had not removed a key bit of information that makes it very not absurd. According to the JAMA article she cited for this paragraph, the NHLBI was not proposing we give all or even most kids cholesterol-lowering drugs or cholesterol screenings.7 The article makes it abundantly clear that these are for children with familial type 2 hypercholesterolemia, a genetic condition associated with chronically high cholesterol levels. People with familial hypercholesterolemia have heart attacks and can die far younger than normal lipid folks. It makes perfect sense to go on a cholesterol-lowering diet or a statin if you have that condition. But of course, Teicholz wants to stoke your outrage a bit so you think the NHLBI are a bunch of incompetent boobs that are completely absorbed (pardon the pun) with the idea of cholesterol.

* * *

Teicholz continues to make the argument against vegetarianism on page 148:

One of the more important early nutrition researchers looking at these questions was Elmer V. McCollum, an influential biochemist at Johns Hopkins University. He performed endless feeding studies on rats and pigs because they, like humans, are omnivores and are therefore considered instructive for human nutritional needs. His book The Newer Knowledge of Nutrition (1921) is populated with pictures of scrawny, scruffy-furred rats raised on poor nutrition, compared to large, lustrously furred ones raised on better nutrition. He found that animals on a vegetarian diet had an especially difficult time reproducing and rearing their young.

She goes on to quote a passage from the book with the author explaining that the vegetarian rats were smaller and lived about half as long as the non-vegetarians. While I was looking for the quoted passage I noticed that basically the entire book is a discussion of rats on deprivation diets of some sort; rat experiments where the researchers deprive them of one or more essential amino acids, vitamins, and breast milk at birth to see what happens.8 This is what the pics of “scrawny, scruffy-furred rats” she refers to are; not necessarily vegetarian rats.

Moreover, I’m not sure that rats make a great proxy for humans. At least I would not be convinced to change my diet based only on rat studies. At any rate, much like her scholarship on the Second Expert’s Report, to find a quote that puts vegetarianism in a negative light you have to ignore paragraphs immediately preceding and immediately following her quoted passage. I’ll give you an idea of what I’m talking about. On page 1599:

The more valid arguments concerning the use of meat as contrasted with the fleshless dietary regimen, are based upon the view that meat is unwholesome and that it contains waste products, which, because of their poisonous properties, tend to do damage to the body tissues. This view is upheld by experimental results. Professor Irving Fisher of Yale conducted extensive experiments with flesh abstainers and flesh eaters, and found the former possessed of much greater endurance than the latter.

After discussing the experiment where the rats’ growth were stunted on a vegetarian diet, McCollum goes on to describe a different vegetarian diet that was more successful. Page 161:

The diet induced growth at approximately the normal rate, and reproduction and rearing of a considerable number of young. The young grew up to the full adult size and were successful in rearing a considerable number of their offspring (see Chart 7).

McCollum then describes another successful experiment where rats were fed anotheriteration of a vegetarian diet and thrived. He even explains why the diet that Teicholz mentioned did not permit the rats to thrive. Page 164:

[T]he diet was of such a nature that the animals could hardly do otherwise than take a rather low protein intake. Secondly, the leaves, which formed the only components of the food supply containing enough mineral elements to support growth, were fed in the fresh condition. In this form the water content and bulk are so great that it would be practically impossible for an animal whose digestive apparatus is no more capacious than that of an omnivorous rat to eat a sufficient amount of leaf to correct the inorganic deficiencies of the rest of the mixture […]

Ladies and gentlemen, this is cherry-picking at its finest.

* * *

On page 152 Teicholz tries really hard to find a reason to dismiss the results of a study:

[The NHLBI] funded a trial called the Dietary Intervention Study in Children (DISC). Starting in 1987, three hundred seven- to ten-year-old children were counseled, along with their parents, to eat a diet in which saturated fat was limited to 8 percent of calories and total fat to 28 percent, and this group was compared to an equal-sized group of controls. Investigators found that those put on the diet low in fat (and animal fat) grew just as well as the children eating normally during the three years of the experiment, and the authors emphasized this point.Yet it was problematic for the study that the boys and girls in the trial did not represent a normal sample. For their study population, the DISC leaders had selected children who had unusually high levels of LDL cholesterol (in the 80th to 98th percentile). In other words, these children could very well have had familial hypercholesterolemia, the genetic condition that causes heart disease through a metabolic defect, which is entirely different from the way that cholesterol is altered by diet. These at-risk children were chosen because they were thought to need help more urgently in fighting the early onset of a life-threatening disease, yet their unusually high cholesterol levels meant that the results could not be generalized to the larger population of normal children.

I would totally agree with Teicholz here if there was significant evidence that hypercholesterolemia would confound growth results in some way. However, it seems obvious to me that she is trying real hard to find reasons to discount the results, and if this is the best she can do then it must be a good study design. Also, the diet is nearly one-third fat. How is this a “diet low in fat”??

* * *

Teicholz hits the vegetarian diet from all possible angles, including the idea that vegetarian children show retarded growth. Page 153:

Slightly stunted growth was consistently found among children eating vegetarian diets. Children were also found to experience growth spurts when incorporating more animal foods in their diets. Growth faltering was particularly pronounced among children on a vegan diet, which cuts out all animal foods.

As evidence she cites a twenty-two year-old review article on reduced fat diets.10Refreshingly, Teicholz doesn’t really misrepresent the article nearly as much as her other claims. However, she does leave out some important details. One important distinction that is not made by Teicholz and is only kind-of made in the review article is the content of the vegetarian diets. What I mean is that the terms vegetarian diet, low fat diet, and low calorie diet are used almost interchangeably in the text. Now a vegetarian diet can of course be low fat or low calorie or both, but it certainly does not have to be.

The author also implies that ridiculously strict vegetarian diets are also included in the review including the Zen macrobiotic diet which the author claims as consisting only of brown rice and water. He also mentions some limitations of this review stating “[N]early all of the studies focus on diets that provide undernourishment in nutrients.” I think it’s reasonable to assume that this can and almost certainly does account for the slight growth stunting and not, as Teicholz would claim, a lack of animal fat.

* * *

Similar to the DISC trial above there was also another study done to test the outcomes of a low saturated fat diet on kids called STRIP (Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project). Teicholz refers to it as a low fat diet, but it simply replaces saturated fat with unsaturated. Evidently there were no adverse effects to growth or coronary disease risk factors. But that doesn’t stop Teicholz from doing her damnedest to try and convince you that the study is bunk. Page 154:

[A]lthough investigators found no vitamin deficiencies, the supplements they provided may have masked this problem. It is also significant that 20 percent of the families in both groups left before the end of the study.

* * *

Page 157:

The British biochemist and nutrition expert Andrew M. Prentice, for instance, hypothesized that the lack of high-fat animal foods was possibly “the major contributor of growth failure” among babies he studied in Gambia. He compared some 140 Gambian infants to a slightly larger group of relatively affluent babies in Cambridge, England; early on, the Gambians and British infants grew almost equally well. When they started to be weaned off breast milk at six months of age, however, their growth curves steadily diverged. The Gambians ate an equal number of calories as did the Cambridge babies for the first eighteen months of life, but the fat content of their diet steadily declined to just 15 percent of calories by the age of two, and most of that fat was polyunsaturated from nuts and vegetable oils. The Cambridge babies, by contrast, ate a majority of calories from eggs, cow’s milk, and meat—a minimum of 37 percent of calories as fat, most of it saturated. By the age of three, the Gambian babies weighed 75 percent less than they should, according to standard growth charts, while the Cambridge babies were growing according to expectations and weighed on average 8 pounds more than the Gambians.

The cited paper does make the case that essential fatty acids are needed for proper growth, and that a lack of dietary fat might explain the stunted growth in the Gambians.11 But some important details in the paper that Teicholz gets wrong or leaves out are that the Gambians did in fact consume less kcals and that Gambian children suffer from infection, disease, and diarrhea more than their Cambridge counterparts.

* * *

Page 158:

Reports from poorer countries in Latin America and Africa, however, revealed that children were eating less fat, with clear implications for nutrition and growth: diets with less than 30 percent of calories as fat started to get nutritionally worrisome, and at 22 percent, they were associated with growth faltering.

If look at the paper she cites for this data, you will find that the poorer countries such as Haiti also consumed FAR LESS kcals than their counterparts from more developed countries. Of course this doesn’t rule out fat as a factor, but I would argue that it definitely confounds the results.

You should also note that this is a cross-sectional analysis which is extraordinarily weak in terms of showing any kind of cause-effect relationship. Teicholz makes this very argument earlier in the book, but you can see here that she has no problem invoking these types of studies when it fits her narrative.

* * *

Teicholz then tries to make the argument that HDL was ignored by the major institutions as a predictor of heart disease. Page 162:

[W]hen diet and disease experts finally began to sidle away from total cholesterol, they did not turn to HDL-cholesterol. Instead, they chose to focus on LDL-cholesterol. By 2002, the NCEP was calling elevated LDL-cholesterol a “powerful” risk factor. The AHA and other professional associations agreed.

LDL was and is a powerful risk factor, but HDL was not ignored. The 2002 report that Teicholz cites has an entire section titled “Low HDL cholesterol as an independent risk factor for CHD.” I could quote about a hundred parts in that report that make the case that low HDL is a risk factor, but I’ll spare you. The report is open access so you can find it and peruse it if you’d like.

* * *

On page 165 Teicholz discusses the Boeing employees trial12 and its implication for women:

[The Boeing women] had followed the most stringent NCEP guidelines for an entire year and had apparently increased their risk of having a heart attack.

She bases this on the study results that the women with high cholesterol levels had a 8% decrease in HDL levels. In the book she doesn’t mention that these HDL reductions only occurred in hypercholesterolemic women, instead implying that all women had their HDL levels go down. Moreover, if one’s HDL levels are at, say, 72 mg/dl and decrease 8% they are still high enough to be considered protective. High HDL levels are not unlikely for women with high cholesterol. HDL as a risk factor for heart disease only occurs when HDL levels get below 40 mg/dl.

* * *

Page 166:

The idea that fat might lead to cancer was first aired at the McGovern committee hearings in 1976, when Gio Gori, director of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), testified that men and women in Japan had very low rates of breast and colon cancer and that those rates rose quickly upon emigrating to the United States. Gori showed charts demonstrating the parallel rising lines of fat consumption and cancer rates. “Now I want to emphasize that this is a very strong correlation, but that correlation does not mean causation,” he said. “I don’t think anybody can go out today, and say that food causes cancer.”

That’s not nearly all Gori presented, but the source of this quote, according to Teicholz is the testimony of Gori in Volume 2 of Diet Related to Killer Diseases (July 28, 1976): 176-182. However, that quote is not found in those page numbers. A similar quote is found on page 185, but it doesn’t include the “I don’t think anybody can…” bit, so I don’t know where Teicholz got those page numbers or that quote.

* * *

Page 167:

It is therefore surprising to learn that as far back as 1987, the epidemiologist Walter Willett at the Harvard School of Public Health had found fat consumption not to be positively linked to breast cancer among the nearly ninety thousand nurses whom he had been following for five years in the Nurses’ Health Study. In fact, Willett found just the opposite to be true, namely, that the more fat the nurses ate, particularly the more saturated fat they ate, the less likely they were to get breast cancer. These results held true even as the women aged. After fourteen years of study, Willett reported that his team had found “no evidence” that a reduction in fat overall nor of any particular kind of fat decreased the risk of breast cancer. Saturated fat actually appeared protective.

The first sentence is actually true. Willett found that breast cancer incidence among those that ate more total fat (even saturated fat) was not higher than those women that ate less total or saturated fat.13 But to claim that total fat or even saturated fat is protective of breast cancer is not supported by the evidence.

Cribbing Taubes Alert

Taubes makes the same mistake regarding the same study on page 72 of GCBC. Coincidence?

* * *

Cribbing Taubes Alert

Page 167:

[T]he most effective fats for growing tumors were polyunsaturated—the fats found in vegetable oils that Americans were being counseled to eat. Saturated fats fed to rats had little effect unless supplemented with these vegetable oils.

On page 73 of GCBC Taubes makes a similar statement:

Adding fat to the diets of lab rats certainly induced tumors or enhanced their growth, but the most effective fats by far at this carcinogenesis process were polyunsaturated fats—saturated fats had little effect unless “supplemented with” polyunsaturated fats.

The reason I am suggesting Teicholz cribbed from Taubes here is not just that both statements are very similar, but also because both cite the same (somewhat obscure) paper and draw the same erroneous conclusion from it. It’s a rather long and dense (and old) paper that very persuasively makes the case that differences in dietary fat – both amount and type – lead to wildly variable results.14 I looked real hard for any kind of definitive statement on dietary fat and cancer in lab rats and this was the best that I found:

Corn and safflower oils and lard consistently enhance tumorigenesis when fed at high levels; coconut oil and fats high in n-3 fatty acids do not, and beef tallow and olive oil are variably effective […]

Go ahead and read the paper. I defy you to come to the honest conclusion that vegetable oils are the only fats that will cause cancer in lab rats.

* * *

Page 168:

Even the NCI’s own studies came up empty-handed—the most recent of those being the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study in 2006. This trial managed to get women to drop their fat intake to 15 percent or less, thereby answering criticisms that the women in earlier studies had not seen any results because they failed to lower their intake of fat enough. But even at 15 percent, the NCI still could not find a statistically significant association between fat reduction—of any kind or amount—and reduced rates of breast cancer.

The study in question does not study rates of breast cancer in general, but rather breast cancer relapses. And according to the results the lower fat intervention did in fact significantly reduce relapses by 24%.15

* * *

Page 169-170, Teicholz discusses the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study results:

Yet to everyone’s alarm and bafflement, the results, published in a series of articles in JAMA, did not come out remotely as expected. […] They had apparently met all their targets, but after a decade of following this diet, they were no less likely than a control group to contract breast cancer, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, stroke, or even heart disease. Nor did they lose more weight.

Teicholz is actually right about most of the results, except for the ovarian cancer and weight loss. Evidently there was significantly less ovarian cancer and weight among the intervention group.16,17

Cribbing Taubes Alert

Taubes makes this same mistake on page 75 of GCBC.

* * *

Page 172:

A review in 2008 of all studies of the low-fat diet by the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization concluded that there is “no probable or convincing evidence” that a high level of fat in the diet causes heart disease or cancer.

This is absolutely true. However, here are some other conclusions by the same text that were intentionally left out because it runs contrary to the saturated-fat-is-sacred-and-unsaturated-fat-is-the-devil narrative18:

- There is convincing evidence that replacing SFA with PUFA decreases the risk of CHD.

- There is convincing evidence that replacing carbohydrates with MUFA increases HDL cholesterol concentrations.

- There is insufficient evidence for relationships of MUFA consumption with chronic disease end points such as CHD or cancer.

- There is insufficient evidence for relationships of MUFA consumption and body weight and percent adiposity.

- There is insufficient evidence of a relationship between MUFA intake and risk of diabetes.

- There is insufficient evidence for relationships of MUFA consumption with chronic disease end points such as CHD or cancer.

- There is insufficient evidence for relationships of MUFA consumption and body weight and percent adiposity.

- There is insufficient evidence of a relationship between MUFA intake and risk of diabetes.

- There is insufficient evidence for establishing any relationship of PUFA consumption with cancer.

- There is insufficient evidence for relationships of PUFA consumption and body weight and percent adiposity.

- There is a possible positive relationship between SFA intake and increased risk of diabetes.

And these aren’t found in some obscure or deep part of the text. They are found in the EXACT same place she found the above quote.

* * *

Page 172:

The USDA and AHA have both quietly eliminated any specific percent fat targets from their most recent lists of dietary guidelines.

If by “quietly” Teicholz means “publicly published in their popular journal that has received widespread attention and 1773 academic citations since 2006,” then, yes, they “quietly” did that. And if by “eliminated any specific percent fat targets” Teicholz means “recommended consuming no more than 7% of kcals from saturated fat,” then, yes, they “eliminated any specific percent fat targets.”19

Chapter 7: Selling the Mediterranean Diet: What Is the Science?

Page 174:

The Mediterranean diet is now so famous and celebrated that it barely needs introduction. The regime recommends getting most of the body’s energy from vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains. Seafood or poultry may be eaten several times a week, along with moderate amounts of yogurt, nuts, eggs, and cheese, while red meat is allowed only rarely, and milk, never.

Anyway, I don’t know why she claims that milk is not allowed. Her cited source does not say that. In fact, it says that dairy is allowed on a daily basis in low to moderate amounts.20*

* * *

Page 180:

In a meticulous, landmark paper in 1989, Ferro-Luzzi tried to create a workable definition of the nutritional patterns characterizing European countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea.

This “landmark” paper has only 145 citations according to Google Scholar, and it’s 25 years old.

* * *

Page 182:

Ferro-Luzzi also took a magnifying glass to Keys’s Greek data expressly to see if she could find some flaw with his 40-percent-fat number. She concluded that his data, like all of those available on the Greek diet of that period, were so scanty and unreliable that there were “few scientific grounds” for the claim of a traditional Greek diet ever being high in fat.

As evidence Teicholz cites a paper published by Ferro-Luzzi in 2002 in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition.21 The paper makes the argument that the diets on Crete and Corfu are not exactly representative of Greek diets as a whole. She actually appears to conclude that Keys’s Seven Countries Study is THE ONLY reliable data on Greek diets so far; it’s all the other data that is scanty and unreliable. Let’s take some quotes from the paper:

In conclusion, the great value of these Key’s studies is that they provide a coherent basis for the only cohort diet-health study published from anywhere in Greece so far.

AND

Our first finding is that there are few reliable dietary studies from Greece in relation to dietary fat, other than the detailed Seven Countries Study. [emphasis mine]

Ferro-Luzzi’s attempt here is to associate the Seven Countries Study with her lower fat version of the Greek diet, claiming that Keys’s data confirms her argument. Do you see how this is basically the opposite of what Teicholz claims?

* * *

On page 188 Teicholz makes the argument that because Willett’s Mediterranean Diet pyramid was published in a journal supplement, it should not be regarded as serious scientific work.

The journal articles that Willett’s team wrote to establish the pyramid were not subject to the peer-review process that scientific papers normally undergo; they had only one reviewer, not the usual two to three. This was because the papers were published, along with the entire 1993 Cambridge conference proceedings, in a special supplement of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition funded by the olive oil industry. These kinds of journal supplements sponsored by industry are standard in the field of diet and disease research, although a lay reader is unlikely to be aware of this financial backing, because sponsorship is not noted in the articles themselves.

If this is the case, then surely Teicholz would never cite a journal supplement in favor of her arguments. Y’know, since the science is tainted by industry money and all. If she did that would make her a hypocrite, right?

- On page 111 Teicholz cites a supplement that favors meat in a healthy diet and downplays its effects on carcinogenesis.22

- On page 75 and 101 she cites a supplemental paper to try and make the case that polyunsaturated fats are dangerous.23

- On pages 165 and 367 she cites an American Journal of Clinical Nutritionsupplement.24

- On page 281 she cites a supplement as part of a claim that unsaturated fats play a role in atherosclerosis.25

- Page 109 she cites a supplement to argue that Seventh-Day Adventist vegetarians weren’t so better off than others.26 (Note: I am not exactly sure this is a journal supplement, though. Teicholz cites it as one and so does PubMed, but the AJCN does not.)

- Page 230 she uses a supplement to claim that tropical oils containing saturated fat are not harmful.27

- Page 160 she cites a supplement as evidence that low-fat diets can lower HDL.28

- Page 202 when she discusses a food frequency questionnaire.29

- Page 144 when she claims vegetarians are not any better off than non-vegetarians.30

- When she discusses Ancel Keys and his research on pages 38, 39, 40, 195, and 205.31

- On page 158 where she makes the claim that more fat = healthier children.11,32–35

- Page 318 when discussing LDL subfractions.36

- On page 92 when she discusses two “scholarly estimates” claiming that polyunsaturated fat was nearly unheard of before 1910.37

- When talking about trans fats and 7-11 on 261.38

- When claiming that vegetarian women don’t fare better than omnivorous women on page 108.39

- On page 324 when she claims that the evidence against SFAs is thin. 40

- On pages 221-222 when she claims that meat consumption in Spain has “skyrocketed” while heart disease has “plummeted.”41

- Page 223, when she claimed that sugar consumption in Spain fell dramatically.41

- On page 154 when she discusses a study on babies.42

- When she claims that children have reduced their intakes of fat in recent decades on page 158.43

* * *

Page 191 Teicholz claims that Keys and Company wooed people to their way of thinking by inviting them to Greece and describing the diet in a very romantic way.

[T]hese getaways were an easy sell. The enormous appeal of the Mediterranean had of course been a factor in influencing Keys and his colleagues from the start, and their rapture for the region came even to suffuse their scholarly work. Henry Blackburn, for instance, who worked closely with Keys, wrote a description of the Cretan male who was “free of coronary risk” for the American Journal of Cardiology in 1986, using language that is unusually florid for a scientific journal:He walks to work daily and labors in the soft light of his Greek Isle, midst the droning of crickets and the bray of distant donkeys, in the peace of his land…. In his elder years, he sits in the slanting bronze light of the Greek sun, enveloped in a rich lavender aura from the Aegean sea and sky. He is handsome, rugged, kindly and virile.The beauty of the landscape and lifestyle, its people, and its diet became united in one, overwhelming swoon.

But what Teicholz does not mention is that the above passage was from an journal editorial and it was satirizing an earlier piece that took a sardonic look at the “Low Risk Coronary Male.”44

* * *

Page 201:

Experts suggested that olive oil might help prevent breast cancer, for instance, but the evidence so far is very weak.

I would argue that the paper she cites to support that statement doesn’t really say that.45Although the statement is phrased in such a way that reasonable people may disagree. Here’s the relevant portion of the paper. I’ll let you decide.

Overall, these observations suggest that olive oil or other oils high in monounsaturated fatty acids may decrease the risk of breast cancer, although more work is necessary before such inferences can be made with confidence. A practical implication may be that animal fat sources in the diet should be minimized, whereas monounsaturated fat sources, such as olive oil, need not be restricted, a recommendation that would be consistent with those for dietary prevention of heart disease.

Teicholz also leaves out what the authors would consider strong evidence regarding red meat and cancer:

In the case of colorectal cancer, associations with fat intake appear to be attributable to red meat intake; indeed, red meat intake is also strongly associated with colon cancer risk in international correlations. In the case of prostate cancer, red meat is also relatively consistently associated with risk, although whether some of this is the result of fat intake remains unclear.

* * *

On page 201, Teicholz claims that the bioactive compounds in olive oil have no benefits.

In “extra-virgin” olive oil, investigators identified a host of “nonnutrients,” such as anthocyanins, flavonoids, and polyphenols, that are believed to work their own minor miracles. They are present in olives because the fruit is dark-colored, a defense developed over thousands of years against exposure to the hot sun. Not all of the effects of these nonnutrients have been adequately explored, but in one case, flavonoids, sizable clinical trials on humans have been unable to show benefits to health.

Apparently by “health” Teicholz actually means CVD and nothing else, since she cites a meta-analysis that only focuses on CVD.46 Not cancer, not diabetes, not anything else. In any case I think she misunderstood the meta-analysis because after reading it I get the distinct impression that flavonoids do, in fact, play a beneficial role in CVD. I’m not sure why I get that impression, but maybe it has something to do with the forest plots that nearly all favor flavonoids and bits of text like this:

[T]his review provides evidence that some flavonoids or foods rich in flavonoids, such as chocolate or cocoa, and black tea, may modulate important risk factors.

AND

The changes in risk factors observed after flavonoid intake are clinically significant.

Also, if you’re curious, meta-analyses on flavonoids and outcomes like cancer and diabetes conclude that they are indeed beneficial.47–49

* * *

Page 203:

[A] few recent studies on animals suggest that olive oil may even provoke heart disease, by stimulating the production of something called cholesterol esters.

This is classic. To support her war on olive oil, Teicholz cites a review article that states in no uncertain terms that unsaturated fatty acids are far more beneficial to cardiovascular health than saturated fatty acids.50 In fact, here’s a quote from the text:

The best types of fat, in terms of improving the lipid ratio, were canola (rapeseed) oil, soybean oil, and olive oil, whereas the worst types were butter and stick margarine. Not surprisingly, all types of fat were better than pure SFA because even the worst of them do contain some unsaturated fats.

Hilarious, but getting back to the olive oil and provoking heart disease… There is a section that questions whether olive oil is as good as we think it is. The author discusses a couple studies using nonhuman primates that were fed dietary cholesterol (to induce atherosclerosis) and three types of oil: palm oil (saturated), safflower oil (monounsaturated), and some oil high in linoleic acid (polyunsaturated). The author then explains that the polyunsaturated oil had the most favorable outcomes in terms of atherosclerosis, while the monounsaturated fat was as bad as the saturated fat in the promotion of atherosclerosis. So if Teicholz wants to use that as evidence that olive oil provokes heart disease because it is high in MUFAs like safflower oil then she better also say that saturated fat also provokes heart disease.

However, other than a couple of animal studies, the article is generally favorable toward both MUFAs and PUFAs and quite unfavorable to SFAs.

* * *

Page 203:

Only because olive oil has been so wildly hyped does the disappointing news about actual scientific findings come as any surprise. Indeed, “surprisingly” is the word that two Spanish researchers used when confronting the data purporting to show olive oil’s heart-healthy effect, and concluding, in 2011, that there was “not much evidence.”

This may be another one of those reasonable-people-may-disagree type things, but I don’t really think the paper concludes that there is “not much evidence.” They do say those words in the abstract, though.51 Here is the sentence: “Surprisingly, there is not much evidence coming from analytical epidemiological studies about this issue.” Which is slightly, but I would argue distinctly, different from how Teicholz phrases that. They say there are not many epidemiological studies on the issue, while Teicholz claims they say there is not much evidence showing a heart-healthy effect. Is there a difference? You decide.

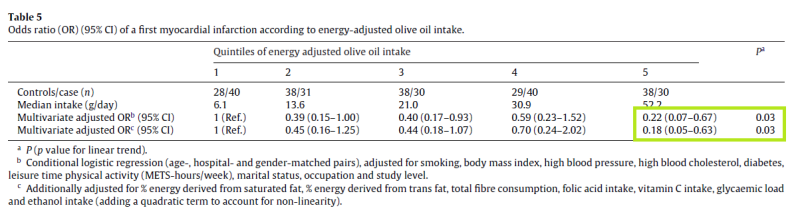

In any case, the paper actually goes on to describe the evidence that exists, and it seems quite positive for ol’ olive oil. In fact, Table 4 and Table 5 show the lowest odds ratios I have ever seen in real life. Most of the studies they review show a significant inverse association between olive oil and some form of heart disease.

* * *

On page 208 she mentions that Antonia Trichopoulou was steeped in bias and not a great scientist (which is… amusing coming from Teicholz).

“Antonia is perhaps guilty, as we all were, of thinking with her heart,” says her former colleague Elisabet Helsing, who, as the Advisor on Nutrition for WHO Europe, was involved in all the early work on the Mediterranean diet.”Many of us in this field, we were led not by the head but by our hearts. The evidence was never so good.” Or, as Harvard epidemiologist Frank B. Hu wrote in 2003, in a break with his colleagues, the Mediterranean diet “has been surrounded by as much myth as scientific evidence.”

The first quote is personal correspondence, so it can’t be verified, but the Hu quote can be. It does appear in the paper, but this is another classic example of Teicholz’s quote-mining. The whole article is what I would consider the opposite of an indictment of the Mediterranean Diet: Hu makes the case that the diet is quite beneficial and versatile. That quote is the only sentence that – when taken out of context – could possibly be construed as incriminating. In fact, much of this book is based on personal interviews with people to which I am not privy. I am uncovering an uncomfortable level of quote-mining by Teicholz which really makes me skeptical of the interviews.

* * *

Page 209, Teicholz discusses a randomized clinical trial of the Mediterranean Diet (the Lyon Diet Heart Study).52 The results clearly indicate CHD benefits, so naturally Teicholz has to do some serious spinning to explain-away these results:

Yet the study had enough methodological problems to give any reasonable person pause: It was small (“hopelessly underpowered,” meaning not enough subjects, as one researcher commented).

I find it strange that a trial that contains 605 participants would be characterized as “hopelessly underpowered.” Let’s take a look at that quote and see what the researcher’s explanation of this is… The cited source of that quote is a paper by Ness et al.53 The “hopelessly underpowered” quote does not appear in the text, nor is there anything similar that might be interpreted as hopelessly underpowered. In fact, there is no mention whatsoever of the Lyon Diet Heart study.

Teicholz continues the dubious Lyon-bashing on page 210 where she states the following:

These problems are described in a paper for the American Heart Association, which found itself in the awkward position of trying to reconcile its own recommended low-fat diet with the success of the relatively high-fat diet used in the Lyon study. The authors concluded that the diet had been “so poorly assessed in both groups” […]

Much like the hopelessly underpowered quote the “so poorly assessed in both groups” quote does not appear in the cited source.54 Teicholz’s next sentence says:

It’s quite possible that the better health outcomes seen in the experimental group were due entirely to what is called the “intervention effect,” they wrote.

They didn’t write that, either. I don’t even think a paraphrasing argument could be made here.

* * *

On page 211 Teicholz discusses the interesting case of Indian researcher Dr. Ram B. Singh who conducted a dietary trial in the early 90s examining common Indian fruits and vegetables and nuts and their effects on heart health.55,56 As it turns out Singh may have fabricated some of his data.57–61 Scandalous!

Teicholz could have left it there as an interesting and accurate anecdote of research malfeasance exposed, but she has to take it a step further and lie about something that didn’t happen.

Years later, however, the Singh study was still being included in scientific literature reviews of the Mediterranean Diet, including an influential one by Lluis Serra-Majem in 2006.

The review in question does not mention or cite that study at all.62 Teicholz is on a roll here with the lies. Maybe she thinks that if you have got this far reading the book then you’re pretty much on board with her arguments and doesn’t really need to provide actual evidence for her claims. The review does cite another study by Singh63 (presumably the same guy), but that study was published in 2002 and has not been linked with any kind of impropriety that I know of.

* * *

Page 215:

If the Israeli trial had never existed, everyone could have assumed that the Mediterranean option in PREDIMED was the best possible regime for health. But that third, low-carb arm in Israel had revealed that an even better option was possible. (Previous shorter trials had found the same thing, as we will see in Chapter 10.)

As evidence for the parenthetical claim she cites a meta-analysis comparing low-fat dietsto Mediterranean diets!64 There is no discussion or mention of any low-carb diets in that paper.

* * *

Page 218 Teicholz makes the argument that the people of the Mediterranean did not eat lean meats like Keys and others recorded, but fatty meats. As evidence she cites a work of fiction:

Nor were the ancient Greeks feasting on chicken. The Iliad describes the dinner given by Achilles for Odysseus this way: “Patrokles put a big bench in the firelight and laid on it the backs of a sheep and a fat goat and the chine of a great wild hog rich in lard.”

Alright everyone, pack it up. Clearly Homer’s poetry written about a thousand years before Jesus was born trumps any kind of scientific research.

* * *

Page 221:

As Italy and Greece slowly grew more prosperous following the war, they started to leave the near vegetarian diet behind. From 1960 to 1990, Italian men came to eat ten times more meat on average, which was by far the biggest change in the Italian diet, yet the sizable spike in heart disease rates that might have been expected did not occur; in fact, they declined. And the height of the average Italian male during this time increased by almost three inches.

Is Teicholz implying that meat consumption decreased heart disease rates and increased height? Is that what she is doing here? It sure looks like it. Is this evidence from a randomized controlled dietary trial? Does Teicholz need to be reminded that correlation does not equal causation?

Her supporting evidence for this is a paper by Ferro-Luzzi (remember her?).65 The paper states that meat consumption increased about 3X not 10X. Sugar consumption increased about 4X. Both fruit and vegetable consumption doubled, as did eggs and fish. At the risk of spelling this out for everyone, even if we were to assume that something like height was due only to diet (which is a stretch), Teicholz still has all her work ahead of her to find good reasons to eliminate all the other dietary changes as a possible factor.

* * *

Page 221-222:

It was the same in Spain: since I960, meat and fat consumption have skyrocketed, while at the same time deaths from heart disease have plummeted. In fact, coronary mortality over the past three decades has halved in Spain, while saturated fat consumption during roughly this period increased by more than 50 percent.

Her evidence for this claim is a cross-sectional study by Lluís Serra-Majem.41 If you were not aware, cross-sectional studies are the least informative and least robust of all epidemiology, except for perhaps a case series. Funny how Teicholz claims throughout the book that epi studies like this one are basically meaningless if they purport to show some link between meat or saturated fat and some negative health outcome, but are just fine to invoke if they fit her narrative.

Meanwhile, if you actually read the study the author says something that Teicholz might not want you to hear:

This paradoxical situation can be explained by expanded access to clinical care, increased consumption of fruit and fish, improved control of hypertension, and a reduction in cigarette smoking.

The author goes on to state that bioactive compounds and dietary antioxidants such as beta-carotene likely also played a role in decreasing CHD. Of course Teicholz never informs her readers of this, because she wants you to think that meat brought CHD rates down.

Teicholz continues:

The trends are the same in France and Switzerland, whose populations have long eaten a great deal of saturated fat yet never suffered much from heart disease. The Swiss ate 20 percent more animal fats in 1976 than in 1951 while deaths from heart disease and hypertension fell by 13 percent for men and 40 percent for women.

True according to one of those cross-sectional, observational studies she cites (which according to her are crappy and meaningless).66 But what she doesn’t say is that other things happened in Switzerland in those years as well according to the analysis: use of anti-hypertensive drugs increased, the economy got much better, there was a migration to urban areas, intake of vegetable fats increased, there was an increased use of oral contraceptives. All of these factors are associated in some way with the decline of heart disease. Do they play a role? It is unclear, and it CANNOT be clear from this study. But that doesn’t stop Teicholz from letting you think that meat may have caused the downturn.

Continuing to the very next paragraph:

This apparent contradiction holds true even on the island of Crete. When the lead researcher for the Greek portion of the Seven Countries study, Christos Aravanis, went back to Crete in 1980, two decades after his initial research, he found that the farmers were eating 54 percent more saturated fat, yet heart attack rates remained extraordinarily low.

The Aravanis paper actually says the opposite of that67:

The 10-year adjusted MCHD [mortality from coronary heart disease] was correlated with total fat in the diet; the correlation with saturated fatty acids was much more significant.

AND

The 10-year incidence rate for CHD was correlated in low order with percentage of calories from total fats, but its correlation with percentage of calories from saturated fatty acids was significantly positive.

Chapter 8: Exit Saturated Fats, Enter Trans Fats

Cribbing Schleifer Alert

It would appear that Teicholz lifts much of the first few pages of chapter 8 from the works of David Schleifer, specifically his 2010 dissertation and a 2012 article which is essentially a condensed version of his dissertation. Schleifer is not attributed in the references section, either. Teicholz doesn’t blatantly copy-paste verbatim, but instead changes enough words to where she has plausible deniability. If you read through both chapter 8 and Schleifer’s dissertation, though, you can easily tell that it’s the same information in the same order.

For instance, Schleifer writes on page 64 of his dissertation “Philip Sokolof founded NHSA in Omaha, Nebraska in 1985 to increase public awareness of cholesterol. Sokolof was motivated by a near-fatal heart attack to spend approximately $15 million of his own money on public education campaigns related to saturated fat and cholesterol.”68 On page 228 of BFS Teicholz writes “Another force pushing food companies to ditch saturated fats for hydrogenated oils was a lone multimillionaire in Omaha, Nebraska, Philip Sokolof […] after suffering a near-fatal heart attack in his forties, made it his mission in his retirement to inform Americans about the dangers of saturated fats.”

- Schleifer: “He seems to have operated the organization mostly by himself, spending approximately $15 million of his own money […]”69

- Teicholz, page 230: “Sokolof founded a group called the National Heart Saver Association, funded by his own millions, and ran it mostly by himself.”

- Schleifer: “Sokolof mailed ‘thousands of letters’ to food manufacturers urging them to eliminate saturated fats.”69

- Teicholz, page 230: “[Sokolof] had mailed ‘thousands of letters’ to food manufacturers urging them to eliminate tropical oils from their products […]”

- Schleifer, page 65: “Irritated at receiving form letters in response, he mounted his first of three ‘Poisoning of America’ campaigns in October 1988.”68

- Teicholz, page 230: “[A]n irritated Sokolof decided that a campaign to shame these manufacturers publicly was his best option.”

- Schleifer, page 65: “These consisted of full-page advertisements in The New York Times, Washington Times, The New York Post, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal and other newspapers […]”68

- Teicholz, references page 383: “Identical full-page ads were also placed in the Wall Street Journal, Washington Times, New York Post, and USA Today, among other papers.”

Both Teicholz and Schleifer even publish the same Sokolof figure and use the same quotes from it.

But that’s not all: it appears Teicholz also takes most of her information on CSPI from Schleifer as well.

- Both discuss the “Saturated Fat Attack” campaign, even though the source material from the 80s is nearly impossible to find.

- Both pluck the same quotes from the same texts, even though the original texts might be 200+ page books.

- Teicholz, page 228: “Hydrogenated oils were therefore ‘not a bad bargain’ when it came to heart disease, the group concluded.” Schleifer uses the same “not a bad bargain” quote in both of his texts.68,69 What are the odds?

- Schleifer: “But it praised Burger King for switching to vegetable shortening in 1986, which it described as ‘a great boon to Americans’ arteries.’”69

- Teicholz, page 228: “Another CSPI campaign successfully convinced movie theaters across America to switch from butter and coconut oil to partially hydrogenated oils in their popcorn poppers. This was ‘a great boon to American arteries’ CSPI judged.” Notice how Teicholz makes it seem like CSPI is referring to movie theaters here, when in fact it is actually Burger King.

The argument about the fight between the American Soybean Association and the Malaysian palm oil industry is also part of Schleifer’s dissertation. They both use the same quote from a NYT article.

- Schleifer, page 71: “’A trade issue is not our concern,’ said Stuart Greenblatt, a spokesman for the Keebler Company, which has said it will remove tropical oils from all its products. ‘American consumers and their health is our concern, and they are telling us they don’t want it. We get piles of mail every day, from everywhere’”68

- Teicholz, page 235: “’We are getting piles of mail every day, from everywhere,’ a spokesman for the Keebler Company told the New York Times. ‘American consumers and their health is our concern, and they are telling us they don’t want it [tropical oils].’”

- Schleifer, page 77-78: “[…] General Mills’ Bugles brand corn chips were the only major American brand that did not reformulate; they were unable to find a technically viable alternative and continued to use coconut oil.”68

- Teicholz, page 235: “Nor could Bugles, the cornucopia-shaped snack made by General Mills, be easily reformulated without coconut oil.”

It is amusing to me that Teicholz accuses Time magazine of lifting her arguments when she pretty blatantly lifts arguments from others. Again, I think it is worth mentioning that Schleifer is not mentioned in her references section, and he most definitely should be. To be fair, she puts his stuff in the bibliography, but never references it. I have no idea why the references/bibliography sections are structured like they are. It just makes everything monumentally confusing when attempting to look something up, plus it takes up an extra 100 or so pages that would not be necessary if they were cited the traditional way. My guess is that she just copied the way Taubes did GCBC, references and all.

* * *

Page 234:

In preliminary studies, palm oil seemed to protect against blood clots.

Nope. The study she cites actually shows that sunflower seed oil protects against blood clots… in rats.70

Chapter 9: Exit Trans Fats, Enter Something Worse?

Page 275:

Research over the past twenty years has allayed the health concerns raised about palm oil during the “tropical oil wars”; the oil may actually be beneficial for health in some ways […]

As evidence she cites a supplemental paper written by the Malaysian Palm Oil Council.71

* * *

Page 276:

More speculatively, research over the past decades has shown that omega-6s are related to depression and mood disorders.

The cited paper actually makes the case that low omega-3 intake is related to depression.72 I suppose if you really stretch your brain you can somehow argue that eating omega-6 will necessarily lead to low omega-3s, which might then cause depression, but that’s way out there.

Chapter 10: Why Saturated Fat Is Good for You

On page 288 Teicholz discusses Dr. Atkins and says

The diet was a tremendous success for him and then for his patients. Atkins tweaked the Wisconsin paper and expanded it into an article for Vogue magazine (his regime was called the Vogue Diet for a while).

I decided to check her bibliography and download the Vogue issue in question via ProQuest. She cites it as “Take It Off, Keep It Off Super Diet . . . Devised with the Guidance of Dr. Robert Atkins,” Vogue 155, no. 10 (1970): 84—85.” I looked on pages 84-85 and it wasn’t there. Strange, right? Where did she come up with that citation? As it turns out (as of this writing, at least) it is cited that way on Dr. Robert Atkins’s Wikipedia page: It turns out that the actual Vogue article is located in the same issue, but different page numbers. My guess is that Teicholz simply copy-pasted the Wikipedia reference and never even saw the original magazine issue.

* * *

Page 298, Teicholz discusses the memoirs of a physician:

With patients on his meat-all-the-time diet, Donaldson found himself “less and less likely to resort to drugs” to combat these diseases.

Her references indicate that the quote is found on page three of his memoir Strong Medicine. It is not. Nor is it clear, if it was the case that Donaldson prescribed fewer drugs, that it was the result of his meat-heavy diets.

* * *

Teicholz then discusses a doctor and researcher Otto Schaefer who visited some “Eskimo” populations. On page 299 she states:

To Schaefer, it seemed obvious that the Inuit were “unable to cope with starches and sugars” to which they had been introduced.

As the source of that quote Teicholz cites a paper titled “Glycosuria and Diabetes Mellitus in Canadian Eskimos.”73 The above quote does not exist in the text. The paper actually makes the case that diabetes was considerably overdiagnosed in Eskimo/Inuit populations, perhaps contrary to the case Teicholz is trying to make in this section, namely that CHOs led to chronic diseases in the Inuit.

* * *

Page 304:

[F]or peak performance during long-distance efforts such as marathons, the common wisdom has been that athletes should eat a lot of carbohydrates the night before. His was the first idea that Phinney wanted to test. “We were pretty sure we’d prove that the carb-loading concept was correct” Phinney told me. To his surprise, he found just the opposite: athletes in his experiments could perform at their best on nearly zero carbohydrates.

These “athletes” were actually obese study subjects.74 These subjects were on a low-carb, calorie-restricted diet and there was no control group of moderate or high-carbohydrate dieters with which to compare the results. In my interpretation the best thing you can say about this study is that obese people are capable of exercise on a reduced-calorie, ketogenic diet.

* * *

Page 305:

[O]ur bodies have no requirement for carbohydrates and can sustain themselves perfectly well, if not better, on ketones.

For this claim she cites a paper from 1956 that measured fatty acids in the blood.75 I don’t know if you can claim that we have no requirements for CHOs and can sustain ourselves as well or better on ketones. The only thing you can really say is that unesterified fatty acids exist in human plasma.

* * *

Page 306:

[T]he ability of blood vessels to dilate (known as endothelial function,” which many experts believe to be an indicator of heart attack risk) has also been shown to improve on the low carbohydrate diet, compared to people on one low in fat. Surprised and skeptical, Volek wondered if all these gains could simply be due to weight loss, since his subjects inevitably slimmed down on the Atkins diet. So he did further experiments keeping his subjects weight constant and found that the low-carb diet yielded the same improvements, even so.

My beef here is with that last statement, the rest is just for context. If you look at the “further experiments” Teicholz mentions you’ll find that the source of this statement is no trial, but rather a letter to the editor of AJCN that criticizes another study that claims that weight loss causes the improved endothelial function and not a load of fat.76,77

* * *

Page 306:

Carbohydrate restriction as a cure for diabetes had been reported by physicians as far back as the late nineteenth century, but Westman’s trials were among the first to give solid scientific backing to the treatment.

On page 398 of the Notes section Teicholz cites a study that predated Westman’s that ostensibly gives “solid scientific backing” to the idea that diabetes could be cured via CHO restriction. Except that the study was done on obese patients and given only 300-700 kcals of nearly pure protein, plus Tums and iron supplements.78 The patients ended up losing a lot of weight. A couple things: 1) “Cure” is certainly a strong word; 2) Can Teicholz be sure that it was not the weight loss alone or the Tums or the iron or the protein or the lack of fat that played a role in the improvement? It must be CHO restriction?

* * *

Page 307:

[T]he American Diabetes Association (ADA) has stood by its low-fat advice, based on the fact that diabetics have a very high risk of heart disease, and since authorities advise a low-fat diet to fight that disease, that is what the ADA recommends to prevent diabetes, too.

The publication she cites actually favorably mentions both a low-fat AND a low-carbohydrate diet.79 In fact, it seems that the ADA might be inclined toward a low-carb diet. Don’t believe me? From the text:

- For weight loss, either low-carbohydrate or low-fat calorie-restricted diets may be effective in the short term (up to 1 year).

- Although low-fat diets have traditionally been promoted for weight loss, two randomized controlled trials found that subjects on low-carbohydrate diets lost more weight at 6 months than subjects on low-fat diets.

- Another study of overweight women randomized to one of four diets showed significantly more weight loss at 12 months with the Atkins low-carbohydrate diet than with higher-carbohydrate diets.

- Changes in serum triglyceride and HDL cholesterol were more favorable with the low-carbohydrate diets.

- In one study, those subjects with type 2 diabetes demonstrated a greater decrease in A1C with a low-carbohydrate diet than with a low-fat diet.

- It is possible that reduction in other macronutrients (e.g., carbohydrates) would also be effective in prevention of diabetes through promotion of weight loss […]

- Low-carbohydrate diets might seem to be a logical approach to lowering postprandial glucose.

Why not mention this? I don’t know. I suppose it is in keeping with the narrative throughout the book that nutrition authorities are incompetent, corrupt, and/or extremely rigid in their advice.

* * *

Page 308:

One of the more extraordinary experiments involved 146 men suffering from high blood pressure who went on the Atkins diet for almost a year. The group saw their blood pressure drop significantly more than did a group of low-fat dieters—who were also taking a blood-pressure medication.

Barely any of that statement is true: blood pressure went down a bit among the low-carbohydrate group, but not enough to be statistically significant.80 Also there was no mention of any group taking a blood pressure lowering medication. I don’t know where she gets that. Also, the study lasted for 24 weeks, not one year. She must have cited the wrong article, this is just too wrong to even be lying.

* * *

Page 309-310:

In 2008, results from a two-year trial were finally published. This was the study in Israel, discussed in the Mediterranean diet chapter, on 322 overweight men and women. The trial was exceptionally well controlled by the standards of nutrition research, with lunch, the principal meal of the day in Israel, provided at a company cafeteria.The study separated subjects into three groups: one eating the AHA’s prescribed low-fat diet, another on the Mediterranean diet, and a third on the Atkins diet. […]Shai found that for nearly every marker of heart disease that could be measured during the two years of the study, Atkins dieters looked the healthiest—and they lost the most weight. For the small subset of diabetics in the study, the results looked about equal for the Atkins and Mediterranean diets. And in every case, the low-fat diet performed the worst.[…] Kidney function and bone density, two primary concerns, were found to be perfectly fine, if not improved, on the Atkins diet.

For these claims Teicholz cites a 2008 study by Shai published in NEJM.81 However, she leaves out a few facts from the study.

- The participants in the low-carbohydrate arm of the study were counseled to consume vegetarian sources of fat and protein.

- The participants were nearly all male, something Teicholz takes umbrage with in chapter 6.

- Although the low-fat diet did seem to “perform” the worst of the three, the Mediterranean diet and the low-carbohydrate diet fared similarly in most respects, not just in diabetics. So I doubt you can say unequivocally that the Atkins dieters were the healthiest when there’s another diet that leads to the same measured outcomes.

Although not discussed by Teicholz there were some other papers published using data from this particular study (referred to as DIRECT, Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial). One of which was a four year follow-up to the study that showed that the Atkins-style dieters gained back most of the weight that was lost.82 The Mediterranean dieters ended up losing nearly double the weight of the Atkins dieters. The low-fat group still had the least amount of weight lost. The Mediterranean dieters also had the most favorable cholesterol and triglycerides.

In another publication kidney function was found to be similarly improved among all three diets.83 Although the authors mention that since the improvement was so similar between diets, the improvement among participants was likely due to weight loss alone rather than the constituents of the diet. The same was said in a publication examining the effect of the three diets on atherosclerosis.84

Another publication from the same trial suggests that the Mediterranean diet is the most beneficial of the three for type 2 diabetics.85

For a more detailed discussion of the Shai study see CarbSane’s posts: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

* * *

Page 314:

In 2011, a group of top nutrition experts published the first high-level, formal consensus paper stating that refined carbohydrates were worse than saturated fats in provoking heart disease and obesity (Astrup et al. 2011).

This is not true. The paper stated that no clear benefit of replacing saturated fatty acids with carbohydrates has been shown, not that refined carbohydrates are worse.86 Moreover, the authors state unambiguously that replacing saturated fatty acids with polyunsaturates does decrease risk of heart disease – something Teicholz unsurprisingly leaves out.

* * *

Page 315:

Remember that the Shai study in Israel found that the Mediterranean diet group, eating a high proportion of calories as these “complex” carbohydrates, turned out to be less healthy and fatter than the group on the Atkins diet, although they were healthier than the low-fat alternative.

Umm… No.

* * *

Page 315:

The Women’s Health Initiative, too, in which some 49,000 women were tested on a diet high in complex carbohydrates for nearly a decade, showed no reduction in disease risk or weight.

Wrong again. There was decreased risk in ovarian cancer and weight.16,17

* * *

Page 317:

[I]n more than a few major studies, LDL-cholesterol levels were found to be completely uncorrelated with whether people had heart attacks or not.

Let’s take a look at these “major studies” she cites, shall we?

The first is by de Lorgeril et al.52 I won’t go into detail, but those in the intervention group had fewer heart attacks and also had lower LDL. From the text: “[T]he trend with time was a decrease in total and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol […]” Although it was not statistically significant, so we’ll give this one to Teicholz.

The second is not a study, but a short commentary by Despres.87 It argues that we should not focus exclusively on LDL, which is not the same as saying LDL is not correlated with anything.

The third is a statin trial that showed reducing LDL cholesterol also reduced coronary events.88 In other words, the opposite of Teicholz’s claim. Some choice quotes from the paper:

This trial provides evidence that the use of intensive atorvastatin therapy to reduce LDL cholesterol levels below 100 mg per deciliter is associated with substantial clinical benefit in patients with stable CHD.Our findings indicate that the quantitative relationship between reduced LDL cholesterol levels and reduced CHD risk demonstrated in prior secondary-prevention trials of statins holds true even at very low levels of LDL cholesterol.

The fourth is a meta-analysis on statins and all-cause mortality.89 Basically irrelevant because it’s only slightly related to the claim of no relationship between LDL and heart attacks.

The fifth is by Castelli et al and is again pretty much the opposite of what Teicholz said.90Want some more choice quotes?

There is a very regular increase of CHD prevalence rates with increasing LDL cholesterol level at each level of HDL cholesterol.The inverse relationship between HDL cholesterol and CHD, when taken over the three levels of LDL cholesterol, is significant (P < 0.001) by a method of Mantel, as are the positive trends of CHD prevalence on LDL cholesterol level.Cross-classification of triglyceride with LDL cholesterol level (fig. 3) leads to the conclusion that either lipid has a statistically significant association with CHD prevalence […]In general, then, when contingency tables are constructed for the three lipids considered two at a time, HDL and LDL cholesterol emerge as consistently significant factors in CHD prevalence […]

Does Teicholz even read the studies she cites?

* * *

Page 324:

Krauss and his colleagues concluded that “saturated fat was not associated with an increased risk” for heart disease or stroke.

Krauss did not conclude that, according to the cited study.91 What was said is that replacingsaturated fat with carbohydrate is not associated with an increased risk of heart disease in women. Notice how they are very different statements?

What about stroke? The paper mentions a couple things:

[S]aturated fat intake may be inversely related to ischemic and/or hemorrhagic stroke, but a meta-analysis including results from 6 other studies did not yield a statistically significant risk reduction.Notably, in humans, the risk of stroke has been related to both the saturated and monounsaturated fatty acid content of plasma cholesteryl esters, which further supports the possibility that the dietary intake of these fatty acids may influence CVD risk by altering cholesteryl ester composition.

Bonus factoid: the paper also states that polyunsaturated fats are inversely associated with developing type 2 diabetes.

* * *

On page 325-326 she discusses a panel event at FNCE in 2010 and produces a quote by Mozaffarian: “its not really useful anymore to focus on saturated fats,” he said. She cites a subsequent publication of the event in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association.92However, that paper does not contain that quote. Nor does the quote appear in other publications by JADA discussing that event and quoting Mozaffarian.93,94

* * *

Page 326: “Americans have dutifiilly followed official dietary advice […]” Pretty sure that’s not true.95 Even by the admission of the USDA.96

Conclusion

After reading The Big Fat Surprise by Nina Teicholz I am frankly disappointed – yet unsurprised – that a book like this was even published. We as readers need to start demanding better fact-checking from our publishers, especially the enormously successful ones like Simon & Schuster. Misinformation like this can actually affect people’s health in a potentially very negative way. I get that publishing companies want to make a profit, but you can publish a compelling pop science book that people buy without misinforming your audience.

*EDIT: The original post contained this statement: I find it interesting that Teicholz uses the word “regime” to describe a diet. Regime means a system of government and is almost always associated with the types of government that are oppressive, totalitarian, dictatorial, despotic, etc. Is she subtly attempting to associate the Mediterranean diet with oppression and death? But I removed it because I had forgotten Teicholz also uses “regime” when describing other diets, such as Atkins.

References

1. Stamler, J. & Epstein, F. H. Coronary heart disease: risk factors as guides to preventive action. Prev. Med. 1, 27–48 (1972).

2. BRODY, J. E. Tending to Obesity, Inbred Tribe Aids Diabetes Study: Inbred Tribe Aids Research Into Obesity and Diabetes Samples Are Preserved 6,000 Involved in Study. N. Y. Times C1 (1980).

4. Marmot, M. et al. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. (World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research, 2007). at <http://www.dietandcancerreport.org/policy_report/index.php>

5. Masterjohn, C. The China Study by T. Colin Campbell. West. Price at <http://www.westonaprice.org/book-reviews/the-china-study-by-t-colin-campbell/>

6. Lichtenstein, A. H. & Horn, L. V. Very Low Fat Diets. Circulation 98, 935–939 (1998).

7. Medical news. JAMA 214, 1783–1794 (1970).

8. McCollum, E. V. The newer knowledge of nutrition; the use of food for the preservation of vitality and health. (New York, The Macmillan company, 1922). at <http://archive.org/details/newerknowledgeof00mccorich>

9. I found two versions of this text: one published on 1918 and another in 1922. Teicholz cites a version apparently published in 1921. My page numbers correspond to the 1922 version.

10. Kaplan, R. M. & Toshima, M. T. Does a reduced fat diet cause retardation in child growth? Prev. Med. 21, 33–52 (1992).

11. Prentice, A. M. & Paul, A. A. Fat and energy needs of children in developing countries. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 72, 1253s–1265s (2000).

12. Knopp, R. H. et al. One-Year Effects of Increasingly Fat-Restricted, Carbohydrate-Enriched Diets on Lipoprotein Levels in Free-Living Subjects. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 225,191–199 (2000).

13. Willett, W. C. et al. Dietary fat and the risk of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 316, 22–28 (1987).

14. Rogers, A. E. & Longnecker, M. P. Dietary and nutritional influences on cancer: a review of epidemiologic and experimental data. Lab. Invest. 59, 729–759 (1988).