Euler's identity

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| mathematical constant e |

|---|

|

| Properties |

| Applications |

| Defining e |

| People |

| Related topics |

where

- e is Euler's number, the base of natural logarithms,

- i is the imaginary unit, which satisfies i2 = −1, and

- π is pi, the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter.

Euler's identity is named after the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler. It is considered to be an example of mathematical beauty.

Contents

[hide]Explanation[edit]

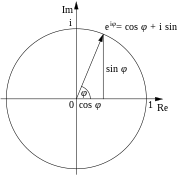

Euler's identity is a special case of Euler's formula from complex analysis, which states that for any real number x,

where the inputs of the trigonometric functions sine and cosine are given in radians.

In particular, when x = π, or one half-turn (180°) around a circle:

Since

and

it follows that

which yields Euler's identity:

Mathematical beauty[edit]

Euler's identity is often cited as an example of deep mathematical beauty.[3] Three of the basic arithmetic operations occur exactly once each: addition, multiplication, and exponentiation. The identity also links five fundamental mathematical constants:[4]

- The number 0, the additive identity.

- The number 1, the multiplicative identity.

- The number π, which is ubiquitous in the geometry of Euclidean space and analytical mathematics (π = 3.141...)

- The number e, the base of natural logarithms, which occurs widely in mathematical analysis (e = 2.718...).

- The number i, the imaginary unit of the complex numbers, a field of numbers that contains the roots of all polynomials (that are not constants), and whose study leads to deeper insights into many areas of algebra and calculus.

Furthermore, the equation is given in the form of an expression set equal to zero, which is common practice in several areas of mathematics.

Stanford University mathematics professor Keith Devlin has said, "like a Shakespearean sonnet that captures the very essence of love, or a painting that brings out the beauty of the human form that is far more than just skin deep, Euler's equation reaches down into the very depths of existence".[5] And Paul Nahin, a professor emeritus at the University of New Hampshire, who has written a book dedicated to Euler's formula and its applications in Fourier analysis, describes Euler's identity as being "of exquisite beauty".[6]

The mathematics writer Constance Reid has opined that Euler's identity is "the most famous formula in all mathematics".[7] And Benjamin Peirce, a noted American 19th-century philosopher, mathematician, and professor at Harvard University, after proving Euler's identity during a lecture, stated that the identity "is absolutely paradoxical; we cannot understand it, and we don't know what it means, but we have proved it, and therefore we know it must be the truth".[8]

A poll of readers conducted by The Mathematical Intelligencer in 1990 named Euler's identity as the "most beautiful theorem in mathematics".[9] In another poll of readers that was conducted by Physics World in 2004, Euler's identity tied with Maxwell's equations (of electromagnetism) as the "greatest equation ever".[10]

A study of the brains of sixteen mathematicians found that the "emotional brain" (specifically, the medial orbitofrontal cortex, which lights up for beautiful music, poetry, pictures, etc.) lit up more consistently for Euler's identity than for any other formula.[11]

Generalizations[edit]

Euler's identity is also a special case of the more general identity that the nth roots of unity, for n > 1, add up to 0:

Euler's identity is the case where n = 2.

In another field of mathematics, by using quaternion exponentiation, one can show that a similar identity also applies to quaternions. Let {i, j, k} be the basis elements, then,

For octonions, with real an such that a12 + a22 + ... + a72 = 1 and the octonion basis elements {i1, i2,... i7}, then,

History[edit]

It has been claimed that Euler's identity appears in his monumental work of mathematical analysis published in 1748, Introductio in analysin infinitorum.[12] However, it is questionable whether this particular concept can be attributed to Euler himself, as he may never have expressed it.[13] (Moreover, while Euler did write in the Introductio about what we today call Euler's formula,[14] which relates e with cosine and sine terms in the field of complex numbers, the English mathematician Roger Cotes (who died in 1716, when Euler was only 9 years old) also knew of this formula and Euler may have acquired the knowledge through his Swiss compatriot Johann Bernoulli.[13])

No comments:

Post a Comment