The Coronavirus Has A Mysterious “Loop” That Lets It Quickly Attack Human Lungs. Here’s How It Works.

How does a relatively common type of virus turn into one so deadly it could spur a pandemic? The answer may lie in its microscopic spikes.

BuzzFeed News has reporters around the world bringing you trustworthy stories about the impact of the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

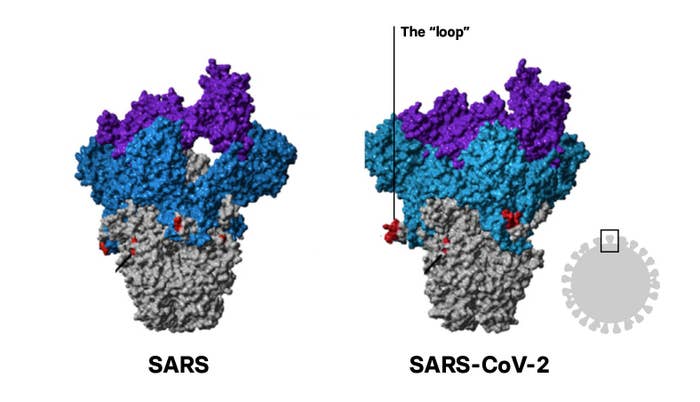

Coronaviruses take their name from the crown of minuscule spikes that bristle from their surfaces. But the new coronavirus wreaking havoc around the world has a distinctive feature on its spikes — a mysterious, loop-shaped oddity that, some researchers suggest, lets it attack a person’s lungs with deadly precision.

This small addition might also explain how the coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, can be transmitted from person to person early on, before symptoms set in — making it so deadly it could spur a pandemic that has killed hundreds of thousands of people.

This microscopic loop has become an obsession of scientists, who are racing to decipher how the new coronavirus works and how to stop it. Figuring out how exactly the virus assaults the body is crucial for understanding what turned an otherwise common type of virus into one that can prevent people from going to work, hugging their friend, and going to the grocery store without a mask strapped across their face.

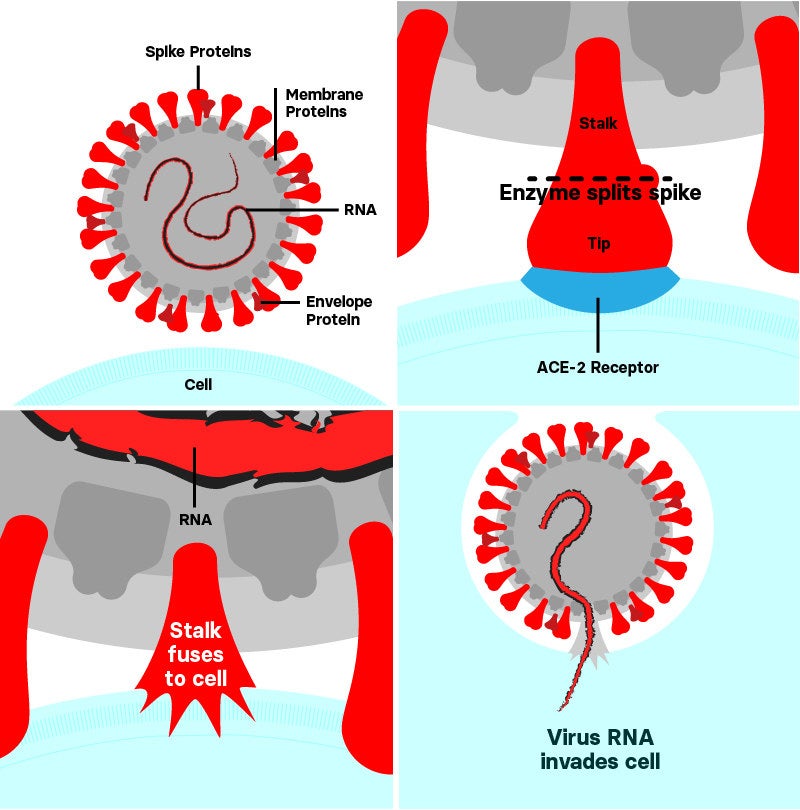

Any coronavirus that infects humans — there are four everyday types that cause 10% to 30% of colds — uses a spike as a sort of harpoon to attach to an otherwise healthy cell.

But SARS-CoV-2’s spike is a bit different. Its genes contain unique instructions that form an additional loop of protein that sits midway on the stalk, between the tip and the rest of the virus. This loop, scientists are learning, could help explain why SARS-CoV-2 is so much more dangerous to humans.

When SARS-CoV-2’s spike harpoons its prey, it docks to a receptor called ACE-2 found on the surface of some human cells.

Then, an enzyme — a substance that, in this case, sits on a human cell and causes a reaction — called furin cuts the loop, splitting the tip of the spike away from the stalk and the rest of the virus.

BuzzFeed News

“What we’ve got is a very unique virus. It is a bit of a Jekyll and Hyde,” said Cornell University virologist Gary Whittaker, referring to the fact that it first attacks like a cold, and then turns deadly only late in an infection.

The loop of protein may help explain how differently SARS-CoV-2 infects humans compared to SARS, its closest human-infecting relative. Most cases brought on by SARS-CoV-2 are mild or symptomless, spreading infections with coughs and sneezes. But deadly cases look like SARS and its relative, MERS.

[If you're someone who is seeing the impact of the coronavirus firsthand, we’d like to hear from you. Reach out to us via one of our tip line channels.]

SARS and MERS — both coronaviruses which caused outbreaks in the past two decades — were relatively contained because infected people were usually only able to spread the virus at roughly the same time they were having severe symptoms, when the viruses were deep in the lungs. This less efficient method of attack allowed humans to know they were sick and to seek help and avoid other people before they could spread the viruses further.

With SARS-CoV-2, people become contagious early in an infection. Most people won’t know they’re sick until three to five days after exposure, while many cases present no symptoms at all, allowing for its wide and invisible spread.

SARS was more than twice as deadly as the novel coronavirus, with a fatality rate of around 11% in every confirmed case, but because it was easier to contain in hospitals, the 2003 SARS outbreak led to 774 deaths before the virus died out. In contrast, because SARS-CoV-2 spreads early in an infection, it has caused upward of 300,000 deaths worldwide.

No comments:

Post a Comment