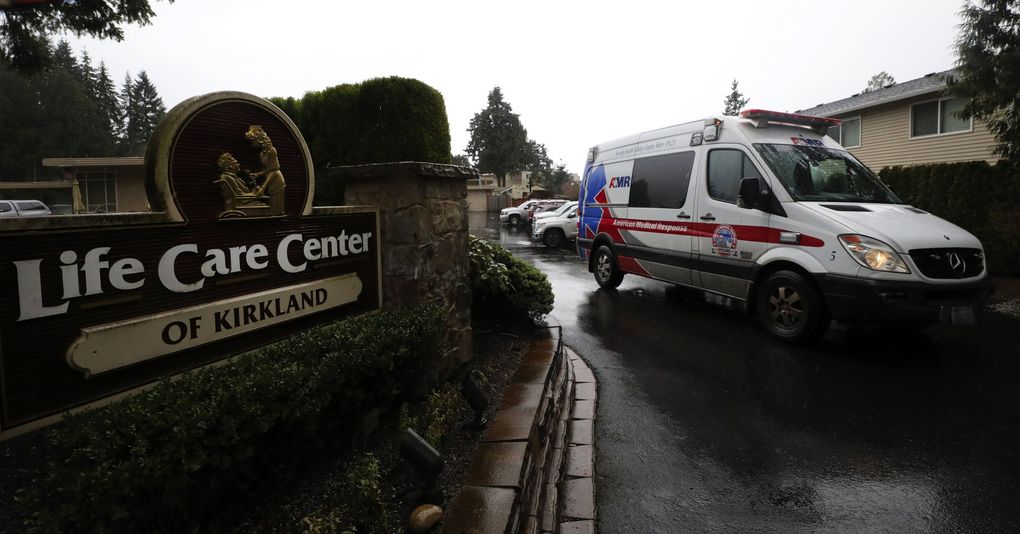

Coronavirus spread at Life Care Center of Kirkland for weeks, while response stalled

From her room inside the nursing home, Judie Shape has heard the coughs of other residents with the novel coronavirus illness down the hall and watched the ambulances come and go for weeks.

Shape, 81, had moved into Kirkland’s Life Care Center on Feb. 26 for short-term care following time in the hospital for blood-clot surgery. It was terrible timing: that same day, Life Care said it notified state officials of an outbreak of severe respiratory illness, which staff had noticed was spreading for weeks.

But the outbreak, which turned out to be COVID-19, may have been circulating in the facility much longer. A Life Care official said staff noticed a respiratory outbreak by Feb. 10, and interviews and a review of 911 call logs obtained by The Seattle Times show it could have appeared even sooner.

Exacerbating the problem: Confusion inside the nursing home and among state health officials over who was responsible for testing sick patients allowed the disease to continue spreading, turning Life Care into the nation’s largest source of COVID-19 fatalities.

Last month, there were 120 residents at Life Care. As of Wednesday, at least 81 have tested positive for the coronavirus and of those, 34 have died, as well as a visitor. About a fourth of the coronavirus fatalities in the U.S. have been linked to the nursing home, according to state and federal data.

Interviews with residents’ family members and a review of 911 call logs obtained by The Seattle Times show a tragedy slowly unfolding. And as nursing homes nationwide prepare to protect residents from a virus that is especially dangerous for the elderly, the situation in Kirkland demonstrates a worst-case scenario and a cautionary tale for other facilities.

Even as state and federal officials were responding to COVID-19 cases at Life Care, the nursing home didn’t obtain enough supplies to test all residents until March 7, and it took another week to test most employees. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said in a report Wednesday that limited access to testing, as well as staff working at multiple facilities while sick and a lack of protective equipment, contributed to the disease’s spread at Life Care.

State and county health officials said it was not their role to provide testing materials to Life Care. The nursing home, in turn, questioned why it would be Life Care’s responsibility to have residents tested in a public health crisis.

“I keep feeling like our government partners keep trying to silo it in, saying, ‘It’s not our fault. It’s not our responsibility.’ But we were underwater,” said Life Care spokesman Tim Killian. “We’ve had to push, push, push just to get what we hoped government would understand would obviously need to be done.”

Life Care’s answers aren’t satisfying for the families of residents who have become ill or contracted the virus.

Shape, a grandmother, is eager to reunite with her family and share memories of her life, which include raising a family with her husband, a former mayor of SeaTac. She has now tested positive for COVID-19.

“This is a series of circumstances that you would never want at the end of a glorious life like she has had,” said Lori Spencer, Shape’s daughter. “I’m just astounded.”

An early call

On the afternoon of Jan. 29, a nurse at Life Care called 911: A woman in her 80s was having trouble breathing, and her blood oxygen level was below normal. “It takes a lot of energy for her to say a few words,” the registered nurse told the dispatcher.

Out of more than three dozen requests for emergency aid from Life Care this year, the call was the first in which staff described symptoms generally consistent with COVID-19.

That same day, Evan Hurley, a union representative for Kirkland firefighters, said a fellow firefighter was exposed to COVID-19 after caring for a patient who had lived at or visited Life Care.

The exposure, Hurley said, was discovered in recent weeks through an examination of records and cases at the Kirkland Fire Department. But Hurley said he could not confirm whether the Jan. 29 call was the source of the firefighter’s exposure. The firefighter ultimately did not test positive for the virus, Hurley said.

Local health officials, however, said they have not found that COVID-19 cases existed at Life Care before late February.

But the firefighters echo a consistent complaint that has surfaced amid the virus’ spread in the Seattle area, and specifically at Life Care: lack of testing.

Some firefighters who responded to calls at Life Care, before and after the outbreak was detected, have still not been tested, according to Hurley. According to Kirkland officials, at least a dozen first responders have been tested, and 29 quarantined for 14 days. Of that group, one firefighter had a confirmed case, and got tested on his own after he became ill, according to Hurley.

Meanwhile, all first responders with symptoms were in the process of being tested, city officials said.

“We’re saying to ourselves, ‘How is it possible that the first responders who are at the front line of this nationally are having to wait so long?’ ” Hurley said. “That should be concerning for the public.”

The nursing home made two more 911 calls about people with breathing problems in early Februrary, and on Feb. 10, recognized that a respiratory illness was spreading.

The disease is discovered

The evening of Feb. 19, the nurse at Life Care made an urgent call: a 60-year-old man’s oxygen levels had dropped to a critically low level. He was unconscious.

Life Care marks that day as the known start of the outbreak, as that’s when the first patient who later tested positive was sent to the hospital, Killian said. At the time, the CDC restricted testing for COVID-19, focusing on international travelers and people with known exposure. Life Care, like the rest of the nation, was in the dark about the fact that the virus was already spreading in the community.

“This was not setting off COVID alarm bells for us; this was setting off pneumonia and influenza alarm bells for us,” Killian said of that time. “There’s a phrase: When you hear hoofs, you think horses, not zebras.”

Still, the frequency at which Life Care sent residents to the hospital with respiratory problems was striking in hindsight.

Nursing homes are required to report suspected or confirmed influenza outbreaks to Public Health — Seattle & King County within 24 hours. Despite concerns that dated to Feb. 10, Life Care said it did not think the situation was unusual until Feb. 26, when Killian said staff tried, but did not reach, the state Department of Health (DOH). The DOH said it had no record of receiving such a report.

We need your support

In-depth journalism takes time and effort to produce, and it depends on paying subscribers. If you value these kinds of stories, consider subscribing.

Life Care notified Public Health — Seattle & King County the following day. So did Kirkland’s EvergreenHealth hospital, which noticed a large cluster of patients from Life Care with respiratory illnesses. One resident was tested for COVID-19, as expanded testing had just become available at the state lab in Shoreline.

Public Health learned on Feb. 28 that 20 residents at the nursing home were ill but had negative flu test results, and the first two cases associated with the nursing home were confirmed. Officials called in the DOH and CDC as nursing home staff became sick themselves and those remaining struggled to respond to the crisis.

The calls for ambulances to Life Care continued as staff sounded increasingly confused and panicked. On Feb. 29, it took one dispatcher three tries and nearly 10 minutes to reconnect with the Life Care staff member who called about a patient with respiratory problems.

The dispatcher’s calls were bounced to voicemails and lines that rang for two minutes straight without an answer. Eventually, the dispatcher reached a nurse, and directed that a mask be placed on the patient to protect first responders.

Several days later, a different call reflected the urgency of the situation.

“He’s turning blue, he’s having a hard time breathing,” one nurse said, while seeking help for a patient in his 60s.

Even as a stream of residents went to the hospital, those left behind — some of whom had shared rooms with residents confirmed to have COVID-19 — were left untested until the nursing home received testing supplies two weeks ago.

At news conferences, Killian has blamed the delay on public health officials. But King County public health and DOH officials said they do not provide testing materials, though the DOH conducts the tests once it receives samples.

“It would absolutely be unimaginable that it would have been our job to get test kits,” Killian said.

The finger-pointing makes no difference to residents’ families.

“When they first noticed there was a problem at Life Care, they should have notified the families and started testing the residents immediately,” said Gina Norton, whose mother has been a resident at Life Care. “But they didn’t. I’m so angry that it took this long to finally test them.”

Inside Life Care today

As Life Care has responded to the crisis, services like bathing, counseling and physical therapy became less frequent, although Killian said nurses and residents have slowly returned to their routines.

Carmen Gray visits her 76-year-old mother, Susan Hailey, from outside her window at Life Care most days now. She said it’s heartbreaking to watch Hailey’s health deteriorate in a rehabilitative facility designed to help her get better.

“And she’s not alone,” Gray said. “These people are here for a reason, and it’s not to lay there and die.”

Many of those who remain can’t leave.

Chuck Sedlacek, 87, was in Life Care to recover from broken bones and a head injury he had suffered in a fall at the same time as the outbreak. He tested positive for COVID-19 on March 8, after his family pushed for him to be evaluated for the illness, said his son-in-law, Clancy Devery.

Hospitals wouldn’t take him because he wasn’t exhibiting the standard COVID-19 symptoms, and other nursing facilities wouldn’t accept him as a resident because he tested positive for the virus.

“It’s pretty devastating,” said Devery, of West Seattle. “We felt like if they had honored our request to be tested and get him out of there, we would not be in the situation we’re in.”

Spencer, the daughter of Judie Shape, said her family’s dilemma could have been avoided too, if Life Care had disclosed the unidentified outbreak that was spreading just days before she arrived in late February.

The virus is now keeping Shape inside Life Care, where Spencer originally expected her mother would stay for just a couple of weeks after recovering from surgery.

“She doesn’t deserve this,” Spencer said.

But Shape hopes, while in isolation, that her chance to reunite with her family will come soon enough. Her bags are packed, her daughter said.

Correction: Judie Shape’s name was misspelled in an earlier version of this story.

Staff reporters Ryan Blethen, Paige Cornwell and Katherine Khashimova Long contributed this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment